How to Watch the ELSA-d Launch in Mission to Tackle Earth's Space Debris

A mission aiming to demonstrate technology capable of cleaning up dangerous space junk is due to launch on Saturday in what will be the first project of its kind.

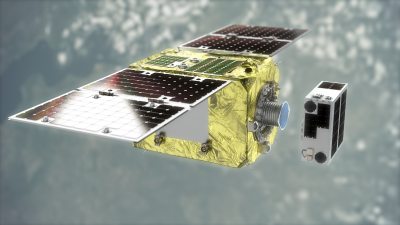

The "End-of-Life Service by Astroscale" demonstration (Elsa-d) involves launching a spacecraft that will carry and release a small piece of space junk into orbit and then attempt to re-capture it with magnets and bring it back down to Earth.

It is hoped the technology—developed by Astroscale, a Japanese company with a subsidiary in the U.K.—could be regularly used to bring down aging satellites and metal orbiting the Earth, now and in the future.

The mission will launch from the Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on a Soyuz rocket at 2:07am EDT Saturday 20th. The mission control center is located in the U.K.

The event will be livestreamed on the developer's YouTube channel here from 1:30 a.m. EDT Saturday.

Other missions to tackle space junk have been envisaged before, but ELSA-d will be the first to trial its particular approach, Astroscale say.

At this stage, ELSA-d will be single-use. Once the cleaner—called the servicer—clamps onto the space junk, it will use built-in thrusters to lower the debris down into the atmosphere, where air resistance will cause both the debris and the servicer to burn up.

However, future iterations of the servicer will enable it to be used multiple times, lowering three or four pieces of space junk back to Earth before being decommissioned itself. Astroscale hopes to showcase this ability in a future mission called ELSA-m.

John Auburn, managing director of Astroscale UK, said in a press briefing: "At the moment, we have a throwaway culture.

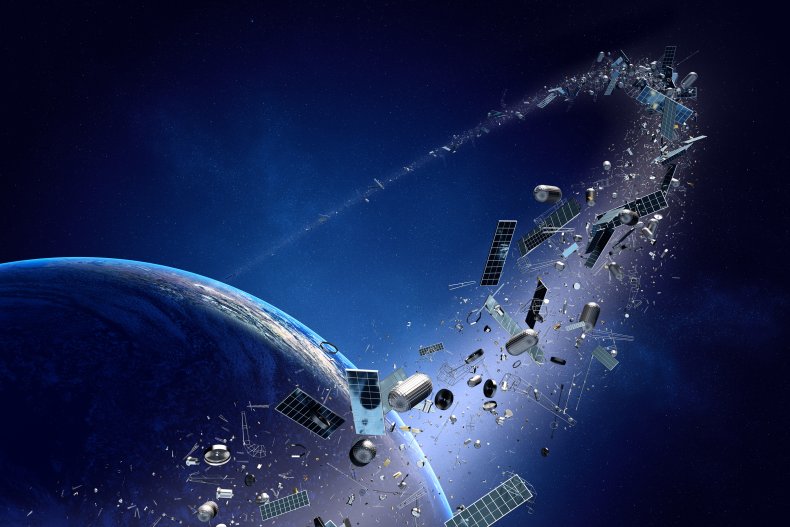

"Space has become more and more crowded, there's a lot of debris. If you like, it's been a disposable economy. Everything that's gone up has been left there, pretty much. And there have been more collisions.

"Scientists believe if we bring down 5 large objects each year that will stabilise the situation, so the threat is the smaller objects but it's the large objects that creates that small debris."

The ELSA-d mission will aim to show how the servicer is capable of clamping onto space debris even if it is rotating, and it will also attempt to effectively lose the piece of debris in orbit before relocating it again.

Astroscale could not give any estimate on how much the future service will cost because it has not yet fully developed its supply chain, the company said.

How Dangerous Is Space Debris?

The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates there are 34,000 pieces of space debris orbiting the Earth greater than 10cm in size, and 128 million pieces between 1mm and 1 cm, according to its figures updates January 8 2021.

It adds that there have been over 560 break-ups, explosions or collisions in space that have resulted in the fragmentation of objects adding to the debris. These objects pose a concern for astronauts on board spaceships like the International Space Station (ISS).

ESA told Newsweek: "The manned modules of the ISS are shielded to withstand objects below 1cm. Objects larger than 10cm can be actively avoided by station manoeuvres. During EVA, astronaut suits provide some protection.

"In general, the risk in the space station altitude is about 5 times smaller compared to 800km, because the environment is cleaner in low altitudes."

'Graveyard zone'

ESA did not specify to Newsweek which countries are most responsible for the majority of space debris, but in general the more active a nation is in space, the more junk it leaves behind.

The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs and ESA say responsible satellite operators should safely remove satellites from orbit at the end of their operational lives, either by returning them to Earth or taking them far away from our planet to the "graveyard zone."

Without human efforts, the issue of space debris is not likely to solve itself quickly. Satellites orbiting the Earth will generally fall back down to our planet by themselves because of very small amounts of atmosphere present in space, even at altitudes several hundreds of miles high. But this can take many years.

Over time, satellites will be slowed down by this residual atmosphere enough that they will eventually de-orbit. How long this will take depends on how far away from Earth they are.

According to the ESA, satellites in low orbits of around 500 kilometers will usually take about 25 years to fall back to Earth by themselves. Satellites at more than double this height, around 1,200 km, will take much longer—around 2,000 years.

Satellites that in geostationary orbits of around 36,000 kilometers—so high that they orbit the Earth at the same speed as the Earth spins—may never fall back to Earth at all.