Muslims believe that the Quran is God’s unalterable word.

Muslims believe that the Quran is God’s unalterable word. Recently, a PIL was filed in the Supreme Court by the former chairman of the Shia Waqf Board, Waseem Rizvi, calling for the removal of 26 verses from the Quran. The petition tries to argue that these verses were interpolated into the Quran by the first three Caliphs of Islam and encourage violence and terror. The reality is that since the compilation of the Quran by the third Caliph Usman ibn Affan, Muslims of all sects have unanimously agreed that the Usmanic codex is the correct version of the Quran. Importantly, neither the first Imam of the Shia, Ali ibn Abi Talib, nor his 11 descendants questioned the veracity of the Quran. Ali was a contemporary of Usman’s and after him became the fourth rightly-guided Caliph, according to the Sunnis. The attempt to blame the Caliphs for the so-called “violent” verses and, thus, linking this to the genesis of modern-day terrorism is a brazen attempt at provoking sectarianism.

Muslims believe that the Quran is God’s unalterable word. For centuries, Muslim scholars have used various hermeneutical and exegetical methods to explain verses that are not immediately easy to understand. Like the Bible, Gita, Talmud and other sacred texts, the Quran too deals with questions of just war, violence and ideas of the “other”. All of these can only be understood once someone has a grip on the language, the history of revelation, context and even grammar of the concerned language. Of course, much before we come to these tools of understanding, the question of intention arises. Our intention, when we approach a text, particularly a holy or sacred text, will determine to a large part what we find in it. These books are not manuals. Instead, they use metaphor, allegory, stories and other devices to convey messages about ethics and morality. These cannot always be viewed through a black and white prism and nor are they always fixed in stone, apart from certain foundational principles. What is forbidden in a certain situation can become morally obligatory in another. For instance, some substances are absolutely forbidden but if, and only if, using such products is the only way of saving someone’s life then the Shari’ah insists that primacy must be given to the sacrality and preservation of life.

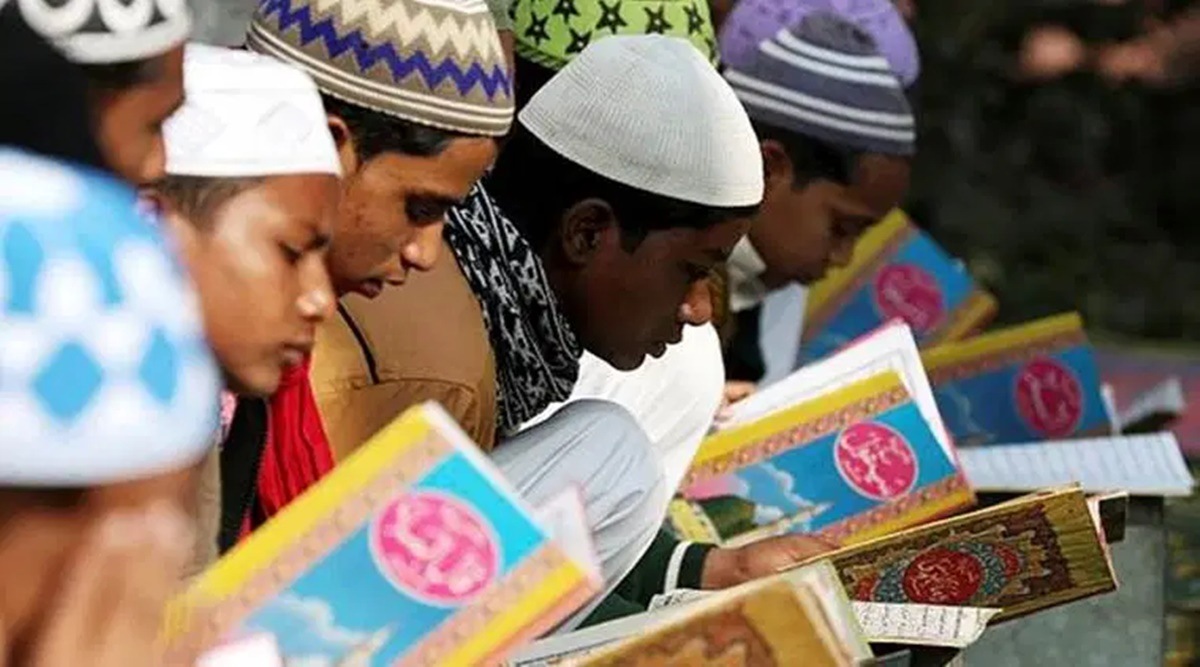

In the case of this petition, there is no need to get into a debate about the transcendence and inalterability of the Quran. We must begin with intentions. Rizvi has previously issued comments about madrassas being factories of terror, Muslims reproducing like animals and has made derogatory and provocative films about Sunni beliefs and practices.

The reasons for doubting his intentions are twofold. Firstly, the Shia Waqf Board is being investigated by the CBI and apart from wanting a clean chit, Rizvi may want to be renominated by the government as its chairman. There is no better way than trying to provoke sectarian discontent amongst Shias and Sunnis. For the past few years, the BJP has time and again sought to project an image of who or what they think is a “good” or “acceptable” Muslim. Some Sufi and certain Shia leaders have been cultivated for this image and exacerbate intra-faith divisions within the Muslim community. As I have argued elsewhere, this search for “the acceptable Muslim” must be seen in the wider context of the global war on terror. For some years, international conferences and conventions, such as the World Sufi Forum, have been held and regular outreach is conducted with Shia and Sufi Sunni leaders which is then projected in the media and on social media. This is done by the BJP as well as by the unofficial Muslim outreach arm of the RSS — the Muslim Rashtriya Manch.

The brazen sectarianism of this petition sits at odds with the position of the greatest Shia scholars who have time and again spoken of the need to desist from speaking ill of figures, especially some of the wives and companions of the Prophet, that are venerated by the Sunnis. Ayatollah Sistani, who was recently visited by the Pope in Najaf (Iraq), has consistently and constantly spoken of the need for unity amongst Shias and Sunnis. In a public statement, he spoke of the need for all Muslims to be united by the belief in God, the Prophet, the Hereafter and the Quran as God’s unalterable word, as well as the importance of prayer, fasting, pilgrimage and charity which bind all the sects together. Once someone from the Popular Mobilisation Forces of Iraq, while speaking to Sistani, referred to the Sunnis as ikhwanuna al-sunna — our brothers the Sunnis. Sistani replied that he should say “anfusuna al-sunna” — the Sunnis, who are us/a part of our own self.

It is important to remember, as a young lawyer Asif Zaidi said to me, that the writ petition is not just a religious attack but is also a political manoeuvre. Many Muslims across the sectarian divide have come out to express their outrage against the writ petition. Senior Muslim leaders of the BJP, including Shahnawaz Husain, have condemned the petition. Even the most unobservant Muslims have felt anger at his statements but I would urge all Muslims to see this entire charade for what it is. It is important to remember the wider political context in which this petition has been filed. Much depends on what the courts do but we must remember that this is a strategy to divide people and divert attention. Don’t let this strategy succeed.

The writer teaches at Ashoka University and is the author of Poetry of Belonging: Muslim imaginings of India 1850-1950 (OUP)