Gilbert and George on their epic Covid artworks: ‘This is an enormously sad time’

As they name themselves dwelling sculptures, I can’t resist asking Gilbert and George what they consider all of the statue-toppling that passed off final 12 months. When I ask for their verdict on the elimination of public works which were accused of celebrating slavery and colonialism, they’re sceptical.

“We would call that shameful behaviour,” says George. “And it’s very odd – because normally those statues are totally invisible. Nobody ever looks at them. I remember, very near my home town, there’s a statue of Redvers Buller, the hero of the Boer war, surrounded by dying Zulus and things. And if you asked people in Exeter, ‘Where’s Buller’s statue?’, none of them knew. It’s a bit silly. Rewriting history is very silly.”

Actually, Exeter’s equestrian statue of Buller doesn’t have “dying Zulus” round it, however its base is engraved with the names of imperial campaigns. A public committee in January advisable its elimination to a much less seen spot – just for Exeter council to vote unanimously, a few weeks in the past, to let it keep.

Gilbert and George assume all such works ought to be revered as cultural monuments. “Leave them as they are,” says Gilbert, “because they’re part of the city. You don’t go to Rome and take down all the Roman sculptures. You don’t destroy all the heads of Caesar – although he must have done very bad things.”

They aren’t remotely heated as they inform me this, by way of a Zoom name from their dwelling in Spitalfields, east London. When I enter the assembly a minute early, they’re already current, completely organized in their fits wanting identical to Gilbert and George. They appear much more composed, in actual fact, than they do in their newest epic collection of photoworks, The New Normal Pictures.

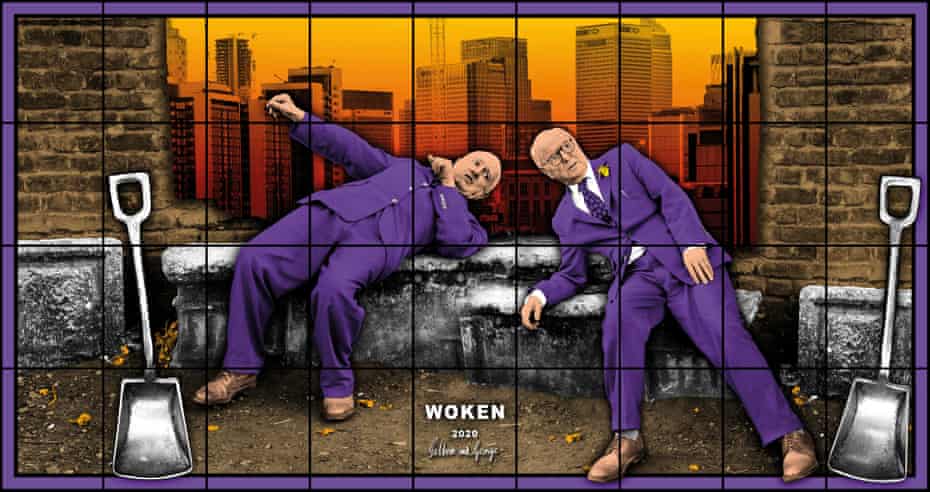

They constructed these comedian but haunting photomontages at their dwelling studio principally throughout lockdown final 12 months, utilizing images taken simply earlier than the pandemic. They look dazed, flattened, pummelled and struggling tragicomically, thrown everywhere in the streets of London like human detritus. In one, Priority Seat, they collapse farcically exhausted on seats at a bus cease. Gilbert Prousch is now 77, George Passmore 79, and they inform me they do generally take the bus today. In one other, Woken, they appear dragged from their graves.

They’re clearly not all that woken. The British empire, claims George, “was a wonderful invention”. But their defence of Victorian statues is a vital perception into their personal artwork. They discover these outdated effigies way more aesthetically highly effective than at present’s public artwork. Those figurative statues from the previous, argues Gilbert, “are fantastic. Modern art is more difficult in the street. Like in Trafalgar Square, you see these artificial sculptures they put up every six months…”

“More or less daft,” shudders George on the Fourth plinth programme, which at the moment boasts a statue of an enormous swirl of whipped cream, a cherry, a fly and a drone.

So what do they like about bronze generals? “It’s human sculpture,” says Gilbert merely. And that takes us to the center of their work. They are nothing if not human. The pair have created artwork that is an outward projection of their personal day-to-day existence. Textbooks will inform you they’re founding figures of conceptual and efficiency artwork. When they met and fell in love at artwork school in 1967, they embarked on a joint profession as “living sculpture” that put the human determine – physique and soul – again on the centre of recent artwork.

It is not solely their private story they painting. Living close to Brick Lane, they give the impression of being, pay attention and take walks, the higher to expertise the lifeblood of east London. They’re conscious how fortunate they’ve been within the pandemic, as self-contained artists: “To be alone and walking the streets of London,” says Gilbert, “is fantastic.” But they’ve additionally witnessed what it’s like for their neighbours.

“Huge lines of coffins and incinerations,” says George.

“Especially in our street,” provides Gilbert. “In the mosque next to us.”

“Every day.”

“Every day there are dead people, three, four.”

“Five, six funerals,” says George. “We even had an illegal rave on Brick Lane which was very exciting. All the police coming to put all the teenagers in the vans. And one young lady appealing to the police, ‘Don’t take him, brother. Please, I beg you brother. Don’t take them.’”

George will get indignant when individuals see the intense facet of this disaster. “Oh,” he says, quoting them. “It’s marvellous, this virus. You can see all the stars at night so clearly without the pollution. Or: It’s so nice – you can drive through London without too much traffic. What a selfish approach. Tens of thousands of people are dying in misery. Husbands and wives and brothers and sisters and mothers and fathers are suffering. It’s an enormously sad time.”

Here is the paradox of Gilbert and George. They are masters of provocation and proudly proper wing, however in addition they have a compassion that might put loads of seemingly virtuous artists to disgrace. It’s an emotional response, not a political one. When I visited them at dwelling earlier than the pandemic, I used to be struck by the mugs on their doorstep, left by their homeless pals. One, George Crompton, seems with them in their New Normal Picture Number Twelve. If this strikes you as self-congratulatory, a Victorian picture of charity, be aware that the image’s title is their precise home quantity, and their road is well-known, so it’s like an open invitation to return and get a cup of tea.

Ah, however the New Normal Pictures, when the gallery can bodily open, shall be on present in posh Mason’s Yard, in an artwork world far faraway from poverty. But perhaps it’s not such an enormous distance from the gallery to the road – actually not based on a story they’re eager to narrate.

“Tell the story of the drug addict who stopped us on Brick Lane,” says Gilbert.

“Yes,” says George. “We were just walking down towards Whitechapel and one of the regular drug addicts came limping along the street with a pair of torn trousers and some horrid strange blood pouring from one ear, and a very grubby face. And as he limped past, he turned round and, referring to our art, he said, ‘I like the Shit ones best.’ This was a reference to their 1990s series The Naked Shit Pictures. “And we laughed – and then we came home and we cried.”

I would really feel extra sceptical in regards to the crying bit if it wasn’t for the truth that, throughout our interview, as George talks about how Aids “bumped off” a few of their greatest pals, I see the tears nicely up in his eyes.

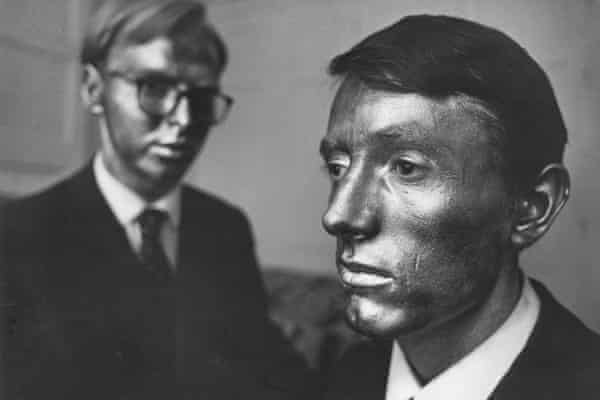

Their compassion appears actual – and they’re no strangers to prejudice. Sometimes their mock-posh language strikes me as a defence mechanism, simply as, in additional than 50 years as a pair, they’ve used their fantastic fits as a form of armour of respectability, to guard their long-proven love for one another. These are two males who first introduced their coupledom to the world by portray their faces silver and wanting like two robots, as they sang a music hall standard that was absurd and archaic, but truly about two homeless males sleeping beneath railway arches: “Underneath the arches / We dream our dreams away.”

George, as an example, likes to name their addicted pals “dope fiends”. But that doesn’t cease them being near their native drug neighborhood. “We even have a favourite dope fiend who is called Daniel,” says George. “He’s very good-looking, he’s very polite. He’s a fantastic person. He disappeared for a few weeks and we asked the other drug addicts, ‘Where’s Daniel?’ One said, ‘He’s inside – he swore at a policeman.’”

I ask in regards to the graveyard whose battered stone plinths seem in among the new footage. It seems to belong to Christ Church Spitalfields – “Hawksmoor’s masterpiece” positioned close by. But, says Gilbert, they’ve now turned their eyes away from spires: “We realised for 45 years we were looking up in the air when we used to walk. Now we’re looking down towards the earth and we start to see a new world: humanity is looking down to earth.”

The New Normal Pictures aren’t nearly their drug-taking pals who frequent the churchyard. They additionally think about the lives of individuals they’ve by no means met, utilizing clues discovered on the road, which seem within the works. In reality, these footage are crowded with stuff they’ve discovered as they stroll London with their eyes to the bottom, from blankets to makeshift beds, from graffiti to occasion balloons, in addition to “drug bags” marked with logos together with an picture of Bob Marley.

As George explains the balloons, you possibly can see how their artwork retains them younger. “When we did the Scapegoat Pictures” – during which metallic canisters for laughing fuel have been made to appear to be bombs – “we collected all of the canisters together with balloons. You can’t inhale the gas from the canisters. You put the gas into a balloon and then you put the balloon to your mouth.” However, they selected to not characteristic the balloons in the long run, “because that would give a festive, jolly, party air to the pictures we certainly didn’t want”.

It’s a helpfully thorough account. “But now, we feel it’s time to use balloons because they begin to speak of blow jobs and intercrural love, illegal rave parties at the moment and, of course, respirators. They seem to be just the job.”

Perhaps, I joke, there ought to be a statue of them each. They say the closest factor to that is their Gilbert and George Centre, a museum of their work that they’re creating within the East End. This morning, they went to see concrete being pumped in to create the bottom ground. The centre will give a house to artwork that lingers within the thoughts like a music corridor melody, beneath the arches, among the many drug baggies. “If,” says Gilbert, “it doesn’t go bankrupt.”

• Gilbert & George: New Normal Pictures is at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London, till 1 May. Public entry is planned from 13 April – see whitecube.com for advance booking.

:strip_exif(true):strip_icc(true):no_upscale(true):quality(65)/d1vhqlrjc8h82r.cloudfront.net/02-15-2021/t_e496bd4d56e3436183da5685a8356d33_name_image.jpg)