Since the military seized power in Myanmar on February 1, demonstrators have been out every night on the streets across the country, banging pots and pans to protest against the military coup. (Photo: Reuters)

Since the military seized power in Myanmar on February 1, demonstrators have been out every night on the streets across the country, banging pots and pans to protest against the military coup. (Photo: Reuters)

The nights are not peaceful in Yangon since the military seized power in Myanmar on February 1. Two weeks into the pro-democracy protests, not much has changed. “The situation is really terrible here,” says a 44-year-old Burmese-Indian, requesting that his name not be used.

The demonstrators have been out every night on the streets across the country, banging pots and pans to protest against the military coup. But it isn’t the noise that’s keeping him awake. It is the deep unease and fear. Residents have started patrolling the streets in fear of raids and arrests, as well as a rise in common crime after the military junta ordered the release of thousands of prisoners.

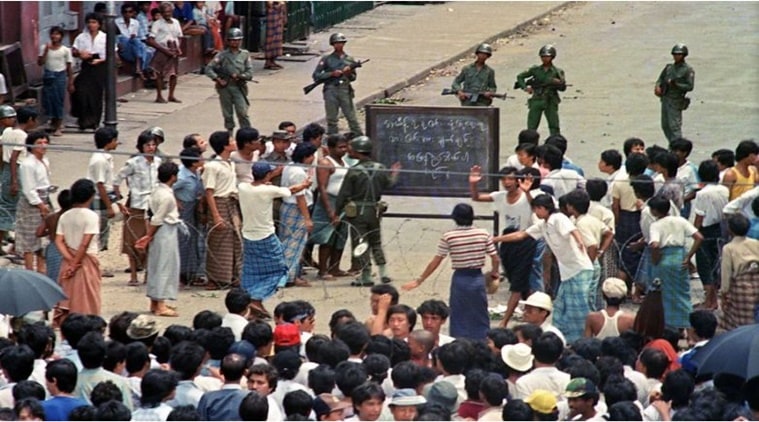

The man’s father, however, has seen worse times, and the impact it had on the Burmese-Indian community. “In 1988, work shut down and food was not available,” says the 68-year-old over a phone call. In August that year, the Burmese military cracked down on anti-government demonstrations that resulted in the death of hundreds of protesters and turned Aung San Suu Kyi into a political icon.

In August 1988, the Burmese military cracked down on anti-government demonstrations, killing hundreds of protesters. (Photo credit: BBC documentary screengrab)

In August 1988, the Burmese military cracked down on anti-government demonstrations, killing hundreds of protesters. (Photo credit: BBC documentary screengrab)

The family first migrated from the eastern part of what was then United Provinces in 1892 and turned to farming. For four generations Myanmar has been home to the family, which is now, like many in the community, involved in the export of pulses.

Although the coup of 1988 is more vivid in his memory, the father also witnessed the aftermath of the 1962 coup. After seizing power, General Ne Win ordered the wide-scale expulsion of Indians from Burma and nationalised business enterprises. “People who had come from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh were poor farmers, so they had very little for the government to take. It was the wealthy Indian merchants who had to leave,” he recalls.

Still, many in the Burmese-Indian community fared better than other minorities, in part because a large number of people worked as farmers and faced comparatively less food shortages if they owned small patches of land, he says.

Although the violence inflicted upon protesters by the Tatmadaw—Myanmar’s military—under Min Aung Hlaing has generated widespread condemnation, a 68-year-old Burmese-Indian, who has spent years researching and documenting the history of the community, says has seen more brutality perpetrated by military rule in Myanmar. “In 1988 they were shooting people on sight. It was extremely violent back then.”

A 1964 edition of Burmese newspaper ‘U Thaung’, known as ‘The Mirror’ in English, with front-page news about the military confiscating property belonging to Burmese-Indians in Yangon. (Photo credit: Kyaw Zin Tun/Facebook; Andrew Soe)

A 1964 edition of Burmese newspaper ‘U Thaung’, known as ‘The Mirror’ in English, with front-page news about the military confiscating property belonging to Burmese-Indians in Yangon. (Photo credit: Kyaw Zin Tun/Facebook; Andrew Soe)

For minorities like Burmese-Indians, the latest military rule has rekindled fears of the past. “1962 was different because the military targeted private businesses like cinema halls, theatres, shops etc, many of which were owned by Indians who weren’t citizens,” he says over the phone.

The socio-cultural impact of the coup on the community was less visible, he adds. “By 1966, they had nationalised everything, even religious institutions and schools.” During the 1960s, his father worked as a Hindi teacher in a school for the community. “The military took control of all schools — those for Christians, Hindus, Muslims — and turned them into Burmese public schools. All communities with Indian heritage in Myanmar had their own schools in the big cities, but they were nationalised.”

“Nobody protested back then, because who can protest alone?” To save their language and culture, Burmese-Indian families began teaching their children at home.

This time, however, large numbers of protesters have come out, including members of ethnic minorities, poets, rappers and transport workers among others, demanding an end to military rule and the release of Aung San Suu Kyi and detained political leaders. Among the Burmese-Indians protesting for democracy are the elderly man’s son and daughter-in-law.

Burmese-Indian women, many from farming families, protest in Zeyawaddy, a small town north of Rangoon, with a large population of Burmese-Indians, against the military coup in February 2021. It was also one of the first towns in Burma where new immigrants from colonial India settled and began working in the agriculture business. (Express Photo)

Burmese-Indian women, many from farming families, protest in Zeyawaddy, a small town north of Rangoon, with a large population of Burmese-Indians, against the military coup in February 2021. It was also one of the first towns in Burma where new immigrants from colonial India settled and began working in the agriculture business. (Express Photo)

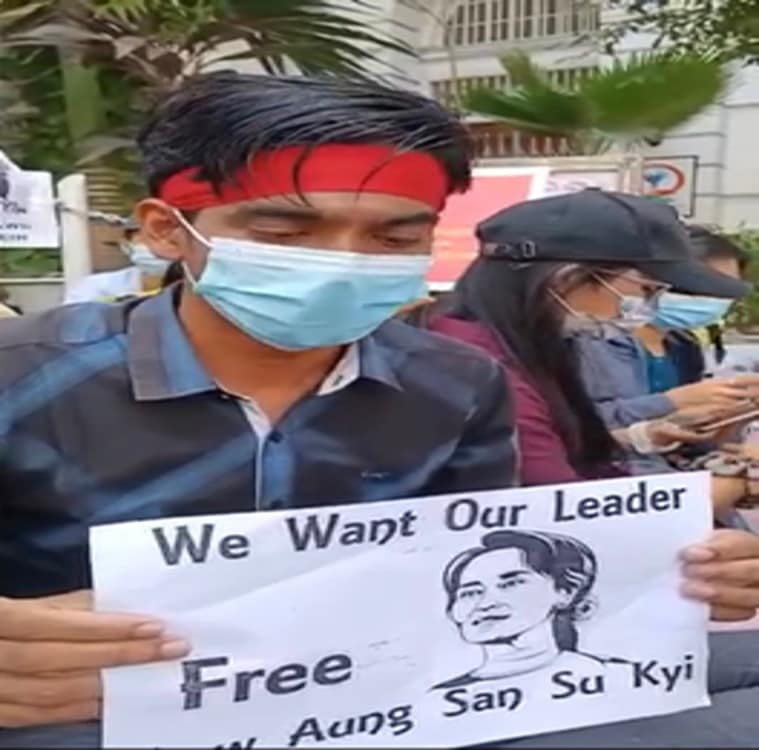

Approximately 10 days ago, hundreds of people first gathered outside the Embassy of India in Yangon in protest against Min Aung Hlaing’s coup. “We are protesting against the embassy because we want the Indian government to help us,” one Burmese-Indian protestor told indianexpress.com, sporting a red bandana and a face mask, holding a poster saying “We Want Our Leader; Free Aung San Su Kyi”.

“The coup will have very severe consequences for democracy and freedom in Myanmar. That is why we are all protesting,” the protestor said, requesting anonymity.

A Burmese-Indian protests against the military coup in February 2021 outside the Embassy of India in Yangon, Myanmar. (Express Photo)

A Burmese-Indian protests against the military coup in February 2021 outside the Embassy of India in Yangon, Myanmar. (Express Photo)

“The Embassy of India is located on Merchant Street, a prominent arterial road of the city, which is being used by protestors since the stir began. For the last two to three days, protesters have been gathering in front of the UN Offices and prominent Embassies in Yangon, including the Indian Embassy,” Indian Ambassador Saurabh Kumar’s office had told indianexpress.com on February 12. Reiterating the Ministry of External Affairs stand on the developments in Myanmar, the Embassy said it has advised Indian citizens to exercise due caution and avoid unnecessary travel in view of the protests.

Large numbers of Burmese-Indians protest against the military coup in February 2021 outside the Embassy of India in Yangon, Myanmar. (Express Photo)

Large numbers of Burmese-Indians protest against the military coup in February 2021 outside the Embassy of India in Yangon, Myanmar. (Express Photo)

Historians trace the origins of anti-Indian sentiments in Burma to the British occupation of the region. But according to a paper by Rajashree Mazumder titled ‘Constructing the Indian Immigrant to Colonial Burma, 1885-1948’, the economic crisis in the 1930s changed the political climate and ideologies, resetting relationships that had existed between communities and ethnic groups in Burma for centuries. “Indian and Chinese diasporic communities found themselves the target of a rising tide of local nationalism in Burma and Malaya and throughout the region. Young local men blamed “immigrants” when they found their paths to employment blocked and their prospects as entrepreneurs limited,” writes Mazumder.

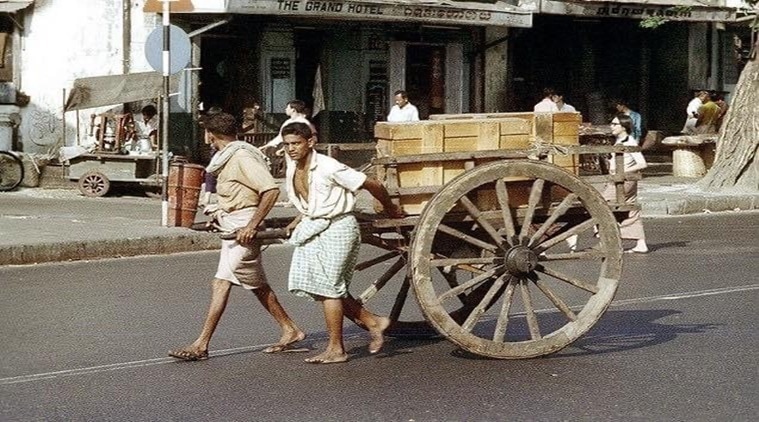

In a photo taken in 1972, two Burmese-Indian labourers pull a wooden cart down a street in Yangon. (Photo credit: Myanmar Old Photos Facebook page)

In a photo taken in 1972, two Burmese-Indian labourers pull a wooden cart down a street in Yangon. (Photo credit: Myanmar Old Photos Facebook page)

Mazumder points to the Indo-Burmese riots of 1938, illustrating just how pervasive these sentiments were, by referencing the writing of a popular Burmese political writer published immediately after the riots: “Betelnut sellers, donut sellers, cloth merchants, storeowners, and wholesalers, all are Indians. Indians are everywhere: shoe makers to factory owners, policemen to high court judge, medical orderly to physician, prison guard to prison warden, all positions are monopolized by Indians.”

During General Ne Win’s coup in 1962, Mazumder writes that “various central government or political leaders have used and abused acerbic anti-Kala rhetoric either to scapegoat an easy targeted minority, or to respond to purely racist popular tendencies.” The term ‘kala’ or ‘kalar’ has a long history of being used to refer to people from the Indian subcontinent, that was turned into an offensive exonym to reference Burmese-Indians during colonial rule and was used to racially target the community.

A photo taken in 1987 of the Indian district in Yangon, where a large number of Burmese-Indian families lived. (Photo credit: Myanmar Old Photos Facebook page)

A photo taken in 1987 of the Indian district in Yangon, where a large number of Burmese-Indian families lived. (Photo credit: Myanmar Old Photos Facebook page)

Burmese popular culture continues to portray the community through these stereotypes, but members of the Burmese-Indian community say they have never considered themselves to be outsiders. In the Chand household, the seamless integration of both Indian and Burmese cultures is clearly visible. In one corner of their home in Yangon, Shyam Kishore has installed a small wooden altar for prayers. Hanging on the wall nearby are photo frames of deities, of which two depict the Buddha. While his father and grandfather never worshipped the Buddha, Shyam Kishore does, as do his children, in what he says is the result of the combination of both his identities that make him a Burmese-Indian.

In a Burmese-Indian home in Yangon, the altar symbolises the unique identity with photographs of Indian deities sharing space with the Buddha. (Express Photo)

In a Burmese-Indian home in Yangon, the altar symbolises the unique identity with photographs of Indian deities sharing space with the Buddha. (Express Photo)

“In two or three generations, it will be difficult to categorise someone as Burmese-Indian, because it will be harder to pick out traits that make us different. We are Burmese who require visas to go to India,” the 44-year-old says. The circumstances of this ongoing political upheaval in Myanmar is different and it has united the country like never before. For minority communities like the Burmese-Indians, the only fear is that they shouldn’t have to pay a price again.

Continue with Facebook

Continue with Facebook Continue with Google

Continue with Google