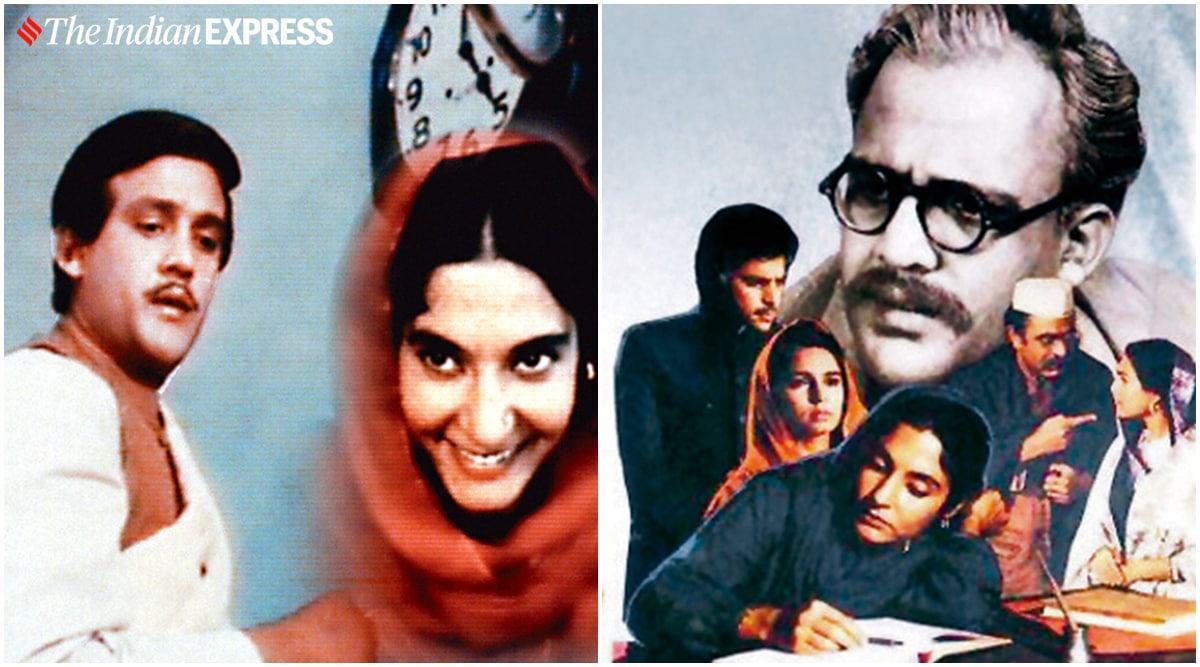

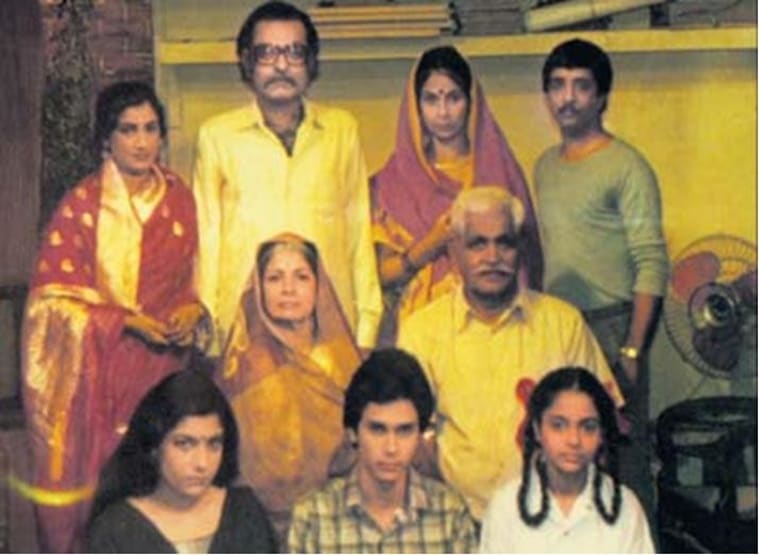

Buniyaad captured both the joys and horrors of living in pre-Partition North India with aplomb. (Photo: Express Archives)

Buniyaad captured both the joys and horrors of living in pre-Partition North India with aplomb. (Photo: Express Archives) “Let us cease to be beasts and become men,” beseeched Mahatma Gandhi to a crowd attending his prayer meeting barely a month before August 15, 1947. Despite Gandhi’s repeated calls against violence and his stiff resistance — “Cut me to pieces first and then divide India” — the Partition of India and Pakistan became a reality in 1947. “The Partition has brought even Gandhiji to his feet,” one panicked character comments in Ramesh Sippy’s Buniyaad that revisits the events of that tragic past through the eyes of Master Haveliram (Alok Nath, in his breakthrough role) and his wife Lajoji (Anita Kanwar, supremely underrated). The Partition riots were one of the worst in Indian history, as millions died on both sides of what is today a bitterly contested border. At a great human cost, both independent nations were unshackled by history, free to leave their worst nightmares behind to conjure a dream worthy of Tagore and Iqbal’s rosy imagination. But then the harsh realities of life aren’t exactly poetry. Certainly for Haveliram and family the journey was far from that. Rather, it was one filled with loss, difficulties and never-ending trials. Aired on Doordarshan in 1987, Buniyaad, along with MS Sathyu’s Garm Hava and Govind Nihalani’s Tamas, has become a canonical cinematic work on the Partition over the years. “It’s the Sholay or Mughal-E-Azam of Indian TV,” actor Mangal Dhillon had once quipped.

The story begins in pre-Partition Lahore, in an old neighbourhood that brims with life, love and friendships. We are in British India and a much youthful revolution is in the air. Uncompromisingly idealistic and rebellious, Haveliram (Alok Nath) hails from the merchant class where his authoritative father (Sudhir Pandey) is used to having the last word. Haveliram has a secure teaching job. But it is his covert ties with Arya Samajis who are involved in anti-British activities and a forbidden love story with a young widow, Lajoji (Anita Kanwar) that attracts the father’s ire. Despite family opposition, he marries Lajoji and turns a new leaf. Life moves on. In the frenzy of Partition, Haveliram is left behind while the rest of his family, poor and homeless, ends up in a refugee camp in Delhi. It is not until much later when their sons are successful that they finally have a home. With the sons growing up, they have complications of their own. Through 105 well-fleshed out episodes, the show covers the arc of Haveliram’s life and relationships all the way through the 1970s when he’s an old man, at a point in life when he could do nothing but look back.

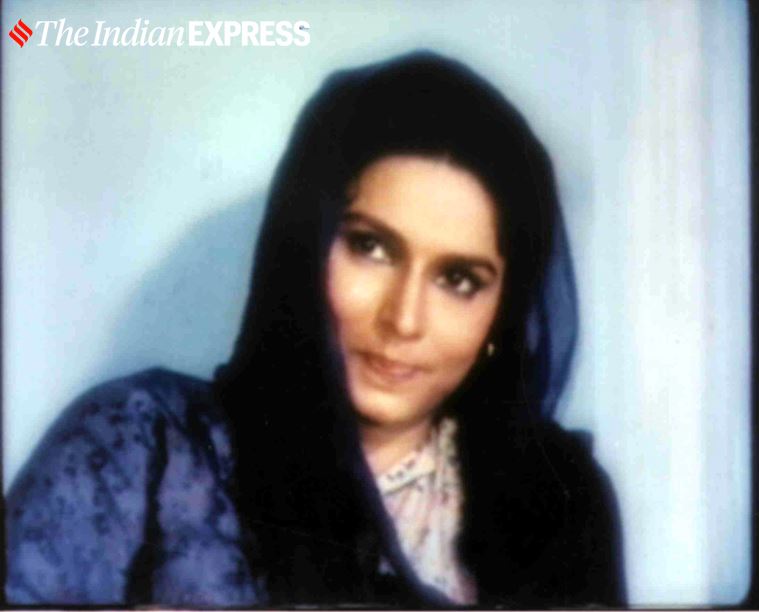

Kiran Juneja as Veeravali in Buniyaad. (Photo: Express Archives)

Kiran Juneja as Veeravali in Buniyaad. (Photo: Express Archives)

A Place called ‘Home’

Buniyaad captured both the joys and horrors of living in pre-Partition North India with aplomb. The communal harmony that it portrays is missing these days, not only on screen but in real life, too. The web site Scroll hailed the show as a “landmark depiction of the Great Indian Family” and it’s easy to see why. Buniyaad has a middle-class flavour whose protagonists have a strong moral code. The large extended family at its centre plods along, very much like a mini-India, despite tragedies and setbacks. The light-hearted conversations, serious fights, jealousies, competitiveness, clash of personalities, generations living under roof and trying to get along, religious temperament, gender roles etc — Buniyaad’s cornerstone lies in the Indian family value systems it espoused. And yet, showrunner Ramesh Sippy finds subtle ways to disrupt this traditional way of life. For example, Lajoji’s character, played with quiet dignity by Anita Kanwar, is an unconventional one for its time. Though a shadow to her husband she has a mind of her own and it is she who keeps the family together and influences her large brood with her empowering thinking and gritty resolve. Equally powerful is Alok Nath’s Haveliram who rebels against his own family. Dubbed ‘satyavadi’ (one who tells the truth), his actions speak louder than words. He comes from a privileged background but doesn’t think twice before throwing himself into the risks inherent in the undercover life of a freedom fighter. He’s clearly proud of his country and her glorious past and blames the British invasion for depriving India of her riches, both material and cultural. “I am not against the English. I am against colonialism,” he tells Vijayendra Ghatge’s Lala Vrishbhan who in the initial episodes is seen enjoying a courtship with Haveliram’s sister Veeravali (Kiran Juneja). Haveliram believes that if India has to evaluate its weaknesses and shortcomings as a nation and civilisation then it must be done “through our own lens, not a British one.” An anglophile who drives his own car and incongruously dresses up like a Sahib (sometimes appearing as though straight out of Chitchor), Lala Vrishbhan emphasises on looking ahead rather than at the past. “I fail to understand the logic in going backwards to be able to get ahead,” he counters, saying, “What place will ancient India hold in the modern world?”

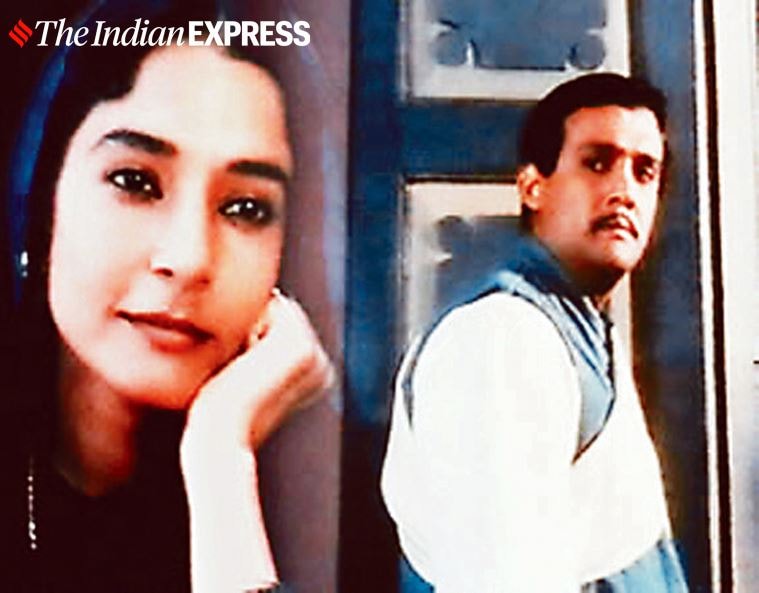

One can surely posit that Buniyaad gave birth to Alok Nath’s sanskari screen image. (Photo: Express Archives)

One can surely posit that Buniyaad gave birth to Alok Nath’s sanskari screen image. (Photo: Express Archives)

While there’s no end to this sort of cultural discussions and ifs and buts (that conversation, ironically, is still relevant in India of 2021), one can surely posit that Buniyaad gave birth to Alok Nath’s sanskari screen image. It was only later that the Sooraj Barjatya school of cinema took this Indianness to its logical conclusion in the 1990s. Today, Alok Nath is the Internet’s favourite meme generator. But do remember, Buniyaad is where it all started. As the Madraswallah blog reiterates, Alok Nath was “thereafter the Babuji, who reinvented this character a zillion times on cinema and television.”

Sholay: Curse or Blessing?

If Partition forms Buniyaad’s soul, the complexities of family relationships is its body and mind. The show has something to say about the great Indian institution called marriage. Arranged marriages are common in India even now. Imagine how orthodox the society must have been about marriage back in the period in which Buniyaad is set. That’s what makes the many love tracks in the show so unusual. In a Partition saga all about the ups and downs of ordinary Punjabi life, it is easy to miss the breezy, old-fashioned love stories tucked in there. First of all, Master Haveliram and Lajoji’s marriage is based on their unspoken romance which was nipped in the bud when Lajoji is married off to a much-older man. Then, there’s Veeravali’s short-lived affair with Lala Vrishbhan. The henpecked Bhushan (Dalip Tahil) and anglicised Lochan’s (Soni Razdan) seems like a love marriage, too. But the biggest love story was the one playing out off-screen. This was between director Ramesh Sippy and Kiran Juneja, a former model. Producer Amit Khanna is said to have referred her to Sippy. For both Sippy and Kiran Juneja, Buniyaad was more than a show. It was a personal milestone.

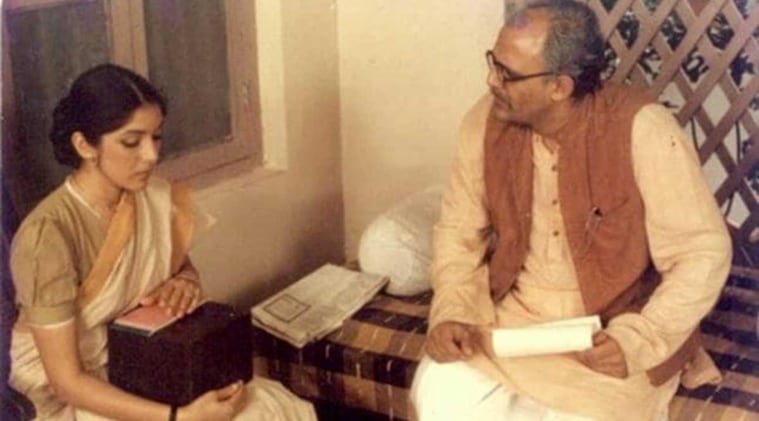

Ramesh Sippy was already a Bollywood mogul when he made his TV debut with Buniyaad. (Photo: DD National)

Ramesh Sippy was already a Bollywood mogul when he made his TV debut with Buniyaad. (Photo: DD National)

Son of the influential producer GP Sippy, Ramesh Sippy was already a Bollywood mogul when he made his TV debut with Buniyaad. There’s a telling scene in the final chapter. Accompanied by his great-grandchildren, it shows Haveliram enjoying Rajesh Khanna’s ‘Zindagi ek safar hai suhana’ on television, a song from Sippy’s very own Andaaz (1971). With Khanna and later Amitabh Bachchan as its face, this was an age that saw filmmaking greats like Yash Chopra, Gulzar, Manmohan Desai, Prakash Mehra and of course, Sippy at the height of their power and popularity. With their roots in what is today Pakistan, Yash Chopra and Gulzar, particularly, reflected on the anguish of Partition through their films and poetry respectively. Chopra started out making films on serious subjects (Partition, Hindu-Muslim unity etc) under the neorealistic spell of his elder brother BR Chopra before going all-out mainstream. Arguing that Chopra’s cinema was more than just romantic showmanship, Swiss getaways and its chiffon chic, author Sidharth Bhatia, in Chopra’s obituary in 2012, pointed towards the director’s radical early films in which the YRF boss “chronicled the lives of the Punjabi refugees who came to India after Partition virtually penniless and became hugely successful.”

In the 1970s, Chopra was God. But Sippy had Sholay. A Bollywood touchstone, whether Sholay has been a boon or bane for its very maker is anyone’s guess. There’s tacit agreement within Hindi cinema that it has eclipsed everything else that Sippy has done. And he’s done some eminently top-notch projects — Shaan, Shakti, Saagar and Seeta Aur Geeta are hidden gems in his repertoire. So is Buniyaad. Coming from a family that was a victim of Partition, Buniyaad might just be his most personal work to date in terms of its story and vision. As far as the scale of the show was concerned, Sippy left no stone unturned. It’s as big a canvas as it can get. One story goes that he had even grander plans for the show, as he had initially thought of repeating his iconic Shakti cast, with Dilip Kumar as Haveliram and Amitabh Bachchan in the role of Kanwaljit Singh’s Satbir.

Buniyaad vs Hum Log

Talking about Buniyaad inevitably invites comparisons with that era’s other great drama, Hum Log. If the two shows appear similar in tone and tenor despite different themes, it could be because one man was writing them. Manohar Shyam Joshi who shot to fame on TV with Hum Log brought literary realism, tight plotting and sharp characterisation to both the tele serials. Due to Buniyaad’s huge cast (a collection of fine performances by Goga Kapoor, Kiran Juneja, Dalip Tahil, Soni Razdan, Mazhar Khan, Vijayendra Ghatge, Mangal Dhillon and Kanwaljit Singh just to name a few), an intensely loyal audience that tuned in week after week and its labyrinthine plot it has been called a ‘soap opera’, at a time when Indian TV was at a nascent stage and nobody probably even knew the meaning of this most American of terms. When modern-day TV czarina Ekta Kapoor churned out saas-bahu soaps at the turn of the millenium in what was a prime-time explosion of the kind Indian couch potatoes hadn’t seen before many sensible viewers excoriated her shows as regressive, wishing for the return of acclaimed dramas like Buniyaad and Hum Log. In 2013, that wish was granted and Buniyaad was welcomed back for a rerun. And just last year, it was brought back again on public demand to ward off lockdown blues, joining Ramayan and Mahabharata. In a press conference in 2013, with his cast and crew in attendance, director Sippy had hoped that new generations would rediscover his labour of love.

The cast of Hum Log. (Photo: DD National)

The cast of Hum Log. (Photo: DD National)

One can’t be sure if the younger audiences are still interested in Partition though writer Christopher Hitchens, in a Vanity Fair essay titled ‘There’ll Always Be an India’ wrote that survivors of this great tragedy mentioned it “as if they were talking about yesterday.” To artist Krishen Khanna, the Partition is a lingering memory. He once remembered disturbing sights at the Ambala railway station as he watched from the sidelines several hapless women waiting for their husbands to arrive, a scene that Khanna recreated later. “Many trains didn’t arrive,” he said, sadly. Khushwant Singh has written about being hopeful that this massacre “would pass, that India and Pakistan would be free members of the Commonwealth and that I would stay on where I was in Lahore.” But that’s not how history played out. This was the “shab-ghazida seher” (night-bitten dawn) that left the revolutionary poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz bitterly heartbroken. Saadat Hasan Manto, the enfant terrible, took the other approach. He poured his Partition frustration into the madly satirical, Chekovian short story Toba Tek Singh. Either Manto was bonkers, or the world was. Mostly, it’s the latter.

Reading about Partition, one feels that perhaps the memories of survivors like Khanna are still fresh and their wounds unhealed. For those like Sippy, who were born in 1947 and grew up hearing stories of Partition from their parents, the turbulent days following India’s independence was a personal tragedy. Those who didn’t witness it first hand or whose families didn’t have to go through it can fall back on such Partition tales as Buniyaad, Dharmputra, Garm Hava and Tamas or see a Khanna painting to imagine the extent and magnitude of the anguish and sufferings. At least, such an exercise can help masses empathise with the victims as well as the remaining survivors of one of the greatest human calamities and the unspeakable pain inflicted on them.

Continue with Facebook

Continue with Facebook Continue with Google

Continue with Google