While the DNA Technology Regulation Bill will help India’s sparse infrastructure and promote scientific crime investigation, it needs adequate safeguards to prevent misuse and allay privacy concerns, India Police Foundation, a Delhi-based multidisciplinary think tank, told the Parliamentary Committee on Science and Technology regarding the bill.

The Foundation warned that sensitive DNA information can reveal family ancestry, skin colour, behaviour, illness, health status, and susceptibility to diseases. This can be used to specifically target individuals of their families using their genetic data.

Lawful and effective use of DNA technology can happen with trained and reliable officials and experts, tools, protocols, and sampling methods. “Most importantly, protocols establishing a trusted chain of custody of samples, reliable and clearly defined processes for analysis, and proper use of expert evidence in court are critical to ensure their evidentiary value. Any gaps in chain of custody will cast suspicion on the integrity of the sample itself,” the Foundation said.

The Jairam Ramesh Committee submitted its report (see our summary) on the DNA Technology Regulation Bill in February. Among its core tenets is the creation of data banks that will house the DNA profiles of not just convicts, but also undertrials, suspects, missing people, and of samples gathered from crime scenes. It was referred to the Parliamentary Standing Committee headed by Ramesh in October 2019. The Committee consulted 15 experts on the bill (see full list here). In addition, Ramesh sought the views of some distinguished jurists and police administrators, including Justice Srikrishna.

Specific changes: consent, board, safeguards for misuse

Stated objective should be limited: The stated objective should specify that use of DNA technology will be limited to establishing the identity of victims, offenders, suspects, undertrials, missing persons and unknown dead people, instead of saying that its “for the purposes” of the same. The Foundation said that this would “shut the possibility of any mischief through universal application of these provisions”.

Regulatory Board: Most board members from the central government or its organisations, “there is scope for more decentralisation”; there is no representation of the Union Home Ministry, it is also “desirable” to have a judicial member from the High court or District Session Judge, it said.

Changes needed around DNA sample collection, consent, and protections: Offences under the Indian Penal Code which permit collection of body samples without collection should have been clearly specified in the Bill’s Schedule. Currently, the Schedule mentions that DNA testing can be used in IPC offences “where testing is useful for investigation of offences”.

- Section 21(1) needs to have safeguards to prevent obtaining consent through coercion, the Foundation suggested.

- Under Section 22, any person who was present during a crime, is being questioned in connection with an investigation, or wants to find a missing relative can voluntarily give written consent to get their bodily substances collected for DNA testing. If such a person is a minor, and a parent refuses consent, then the investigator can approach a magistrate to order the collection in any case. According to the Foundation, for the first criteria, it’s possible that the person in question is a witness, not necessarily a suspect or accused.

There is “no need to openly extend” DNA sample collection to the crime scene index or to include witnesses in it. The second criteria (connection with investigation) is “too wide and subject to misuse”; this can be safeguarded “through a scheme for obtaining permission of a jurisdictional judicial magistrate for collection of samples”, it said.

- The presence of a lady doctor/forensic scientist must be mandatory for collecting intimate bodily substances or carrying out intimate forensic procedures on a women. Intimate bodily substances and forensic procedures include collection of blood, semen, tissue, fluid, urine, pubic hair, swabs from an orifice other than the mouth, swabs from external genital area or breasts, or a photo/video recording, or skin and tissue from an internal organ.

Safeguards needed to prevent misuse of data and information in the custody of the DNA bank. To access information in the DNA Data Bank, law enforcement authorities / investigating agencies must submit a written request with adequate justification and FIR number under investigation, and signed by a police officer of prescribed rank only.

When it comes to access of DNA profiles to foreign or international agencies, strict and clear protocols must be established. “Information should be handed over only after obtaining an order of an Indian Court having jurisdiction. This is the procedure that other democracies follow,” it said.

Extension of DNA Tech to multiple laws questionable: The bill has not provided a justification for why use of DNA technology has been extended to certain laws special and local laws. “How can DNA evidence help resolve cases of medical negligence?” the Foundation asked, noting that federal laws around termination of pregnancy and the law prohibiting sex determination are already included.

- How can DNA help in the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955 (no injuries are caused-only spoken words)

- No justification of collecting DNA information for routine MV Act cases (death or injury because of accident are already covered under Sections 304 A, 337/338 of IPC)

- Immigration/emigration cases – while DNA information may help in some cases, setting up a data bank of all immigrants or emigrants is likely to be contested; this needs clarification

Suspects’ Index must be temporary and must be automatically deleted in case of no arrest, it should not give other handles to extort bribes.

Judicial review: Under Section 57, no court has jurisdiction to entertain any suit or proceeding in respect of any matter which the Board is empowered to do. This is totally unwarranted, as it excludes the jurisdiction of courts, including high courts and the Supreme Court.

Penalties for offences: Penalties provided theft, leaking, or unauthorised sharing & usage of DNA information should be a minimum of 10 years of imprisonment extendable to life, and a fine up to 1 lakh for each instance involved. The proposal of imprisonment up to 3 years and fine up to 1 lakh for collective data isn”t deterrent enough, the Foundation said.

Private DNA labs should be audited regularly by well qualified technical staff of FSL, following an established procedure.

UN standards: The bill must meet the UN standards of security and privacy.

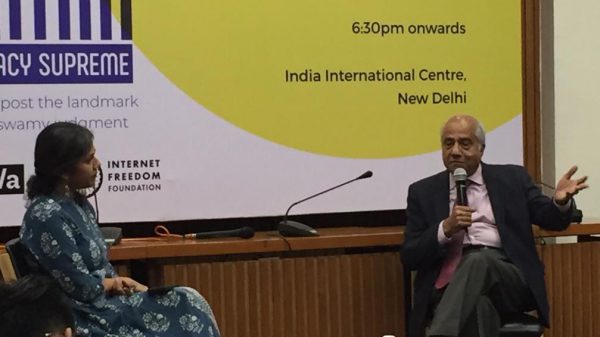

Former CBI director RK Raghavan: ‘Law nearly perfect’

According to former CBI director RK Raghavan, the DNA Technology Regulation 2019 is “nearly perfectly” drafted and does not need “any drastic changes”. While there are the usual apprehensions about misuse of DNA data bank by law enforcement or adversaries of suspects whose data are stored, these exist world over, he said.

“These exist the world over. There is nothing like a foolproof law just as there is no perfect human being who will not be swayed by pecuniary considerations or personal prejudices.”

Lawmakers can be faulted if they do not provide safeguards against the possibility of authorities coercing people into giving DNA samples, or if they fail to secure systems that store DNA. The requirement of written consent of a suspect for an offence that is punishable with imprisonment of seven years is enough guarantee against coercion, Raghavan said. He then went on to say that DNA samples are also used to acquit those wrongfully charged of crimes.

Raghavan also downplayed fears of possible vulnerabilities in the DNA data bank. “The DNA data bank is a computerised system. It is as safe as the best computer systems in the world are. And it has been well established – particularly after Wikileaks- that to expect 100 percent security is preposterous. Ultimately a system is as strong as its weakest link,” he said.

Also read