In the Absence of Light: celebrating the history of black artists in America

“I get up at 7.30 in the morning and then I’m at my computer working, thinking about new ideas, pushing along the projects that I’m involved in,” 70-year-old Sam Pollard explains. The documentary film-maker, as an editor, continuously collaborated with Spike Lee on movies akin to Mo’ Better Blues, 4 Little Girls and Bamboozled. His storied directing profession options the seminal civil rights docuseries Eyes on the Prize, the electrifying blues documentary Two Trains Runnin’, and the Academy Award-shortlisted MLK/FBI.

Speaking by video name from his New York City residence, Pollard’s hearty snigger accompanies a nonetheless buoyant curiosity. “Even at this stage of my career, I still love what I do. That’s a big part of keeping me in the game. I love making films. I love talking about films. I love the process of showing how films are put together,” he says. His boundless power – which features a day by day schedule of interviewing by Zoom, selling and creating new initiatives, and instructing at NYU – has propelled him to launch 10 separate documentaries over the final six years that captures each the distinguished and little-known figures in African American history.

His new HBO-produced movie Black Art: In the Absence of Light, in that very same spirit, recounts David Driskell’s groundbreaking Two Centuries of Black American Art. First mounted at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) in 1976, it’s an engrossing survey of African American artwork since 1750 that impressed attendees and future artists, and spurred questions surrounding illustration.

“Originally, Henry Louis Gates and myself thought we should build it around Thelma Golden’s 1994 exhibition that was at the Whitney, The Black Male. She was the one who suggested we reach out to David Driskell,” recollects Pollard. “I met up with David at his apartment on 100th Street and Central Park West. We had a very nice dinner and talked about the genesis of Two Centuries and the artists that he included in the exhibition.” Driskell’s eager curation supplied Pollard’s movie with a simple entry level to not solely unearth the legacy of the Lacma occasion, however to doc foundational black artists like Elizabeth Catlett, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Selma Burke and Norman Lewis. A group of creatives specializing in portray, structure, ornamental arts and drawings who used the arts to claim their energy.

Pollard may have constructed a documentary solely regarding Two Centuries. The exhibit is so wealthy in breathtaking works by nonetheless usually unknown black artists, as evidenced by the movie’s luxurious montages of the items. Pollard, nonetheless, ambitiously opted to increase the movie’s scope to incorporate up to date artists who may additional communicate to the occasion’s legacy.

He interviewed Carrie Mae Weems, Hank Willis Thomas, Jordan Casteel, Faith Ringgoldand Amy Sherald in New York City. Then traveled to Maine to fulfill with David Driskell. Flew to Chicago for Kerry James Marshall and Theaster Gates, then to Atlanta to see Radcliffe Bailey, Los Angeles for Betye Saar and her daughter Alison Saar, and at last to San Francisco to talk with Richard Mayhew and Mary Lovelace O’Neal. These inclusions allowed Pollard to flex Black Art: In the Absence of Light right into a memorialization of Two Centuries whereas investigating the current panorama in the artwork world for African American artists.

Pollard, for example, nimbly critiques gatekeeping white critics and curators by first spotlighting the 1969 exhibition Harlem on My Mind. The curation led by Thomas Hoving included little or no enter from black voices, and took an unsettlingly anthropological strategy to highlighting the history of Harlem, ensuing in protests surrounding the Met. Later whereas reviewing Two Centuries, white critics akin to the New York Times author Hilton Kramer bewilderingly requested: “Black Art or Merely Social History?” “The question used to be ‘What critics write anything about black art?’ It was such a rare occurrence. Then it became, ‘They really don’t know what they’re talking about when they do.’ That’s not universal, but there were a lot of things that they missed,” explains the conceptual artist Fred Wilson, who’s featured in the documentary.

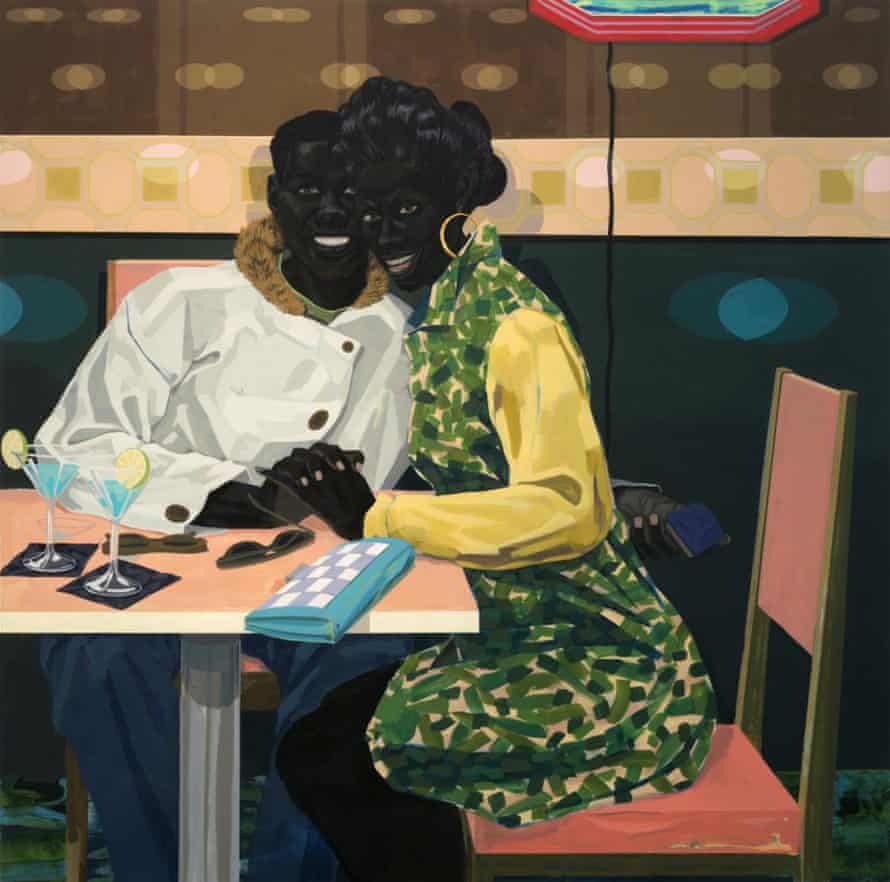

The lexicon to critique black artwork partly stems from a vital query posed by the artist Norman Lewis: is there a black aesthetic? “The notion of a black aesthetic was something that was very important in the 60s and 70s coming out of the civil rights struggle and the black power movement,” says Pollard. In Black Art: In the Absence of Light the various textures of that aesthetic are placed on full show. From Kara Walker’s provocative black cut-paper silhouettes to Kerry James Marshall’s emphatically black-painted figures to Theaster Gates’s evocative sculptures composed of clay, tar and reclaimed constructing supplies.

“The next iteration of the discourse that the film could engender is thinking about the idea of diaspora. For example, I was very much influenced by the transatlantic. Meaning someone like Isaac Julien or the late, great Stuart Hall. They had a much more nuanced understanding of say blackness, if you will, or queerness, in terms of gender,” clarifies the artist Lyle Ashton Harris. His arresting collection of black-and-white photographic prints, Constructs, generated acclaim and rebuke from critics in the Thelma Golden-curated Black Male exhibition, which is featured in Pollard’s movie. “Initially as someone who was young at the time, it was challenging to have this amazing yet vitriolic response. Not only with racism from the art world toward Thelma, the Whitney, etc but also the critique of the community, whether that’s the Whitney or the west coast.”

Black Art: In the Absence of Light demonstrates how illustration in its multiplicity is distinctly empowering. Take Kerry James Marshall’s wide-eyed enthusiasm when relaying how, at 21 years previous, he attended Two Centuries. “The scope of the show, the amount of work that was available that you’d only seen in books before. For an artist … seeing the real thing matters a lot,” relates Marshall. Or how Pollard’s movie opens with the erudite Driskell showing in a cream-colored go well with on nationwide tv with Tom Brokaw to eloquently focus on the goals of his exhibition. The second is twofold: Driskell is sharing the inherent illustration at the coronary heart of Two Centuries whereas being a black man chatting with a wider viewers on The Today Show. Both proliferate the consciousness of black individuals in completely different, vital methods.

Pollard additionally carves out sections to underscore Faith Ringgold’s feminist inventive wrestle to narrate the significance of feminine artists, and to make identified the significance of herself, even in the face of the male-dominated energy construction prevalent in the artwork world of the Nineteen Sixties. He additionally follows Richard Mayhew, Driskell, Radcliffe Bailey and Gates into their studios to seize them at work. “For me, it really opens the film up so you’re not just listening to them talk about their work, but you’re seeing them at work, which is very important,” says Pollard. Seeing black artists mine their craft is as substantial as when somewhat woman sees Amy Sherald’s Michelle Obama portrait or somewhat black boy comes into contact with Kehinde Wiley’s Barack Obama or once they see Marshall’s informal work set in barbershops and barbecues.

Pollard additionally relates the significance of black patronage by that includes avid superstar collectors to postulate about the oncoming gold rush of black artwork. “There have been generations of Afro-American collectors, for example, Clarence Otis, the former CEO of Darden restaurants. He and his wife Jacqui, have put together an extraordinary collection,” explains Ashton Harris. “Even when he didn’t have money, Driscoll as a young man started buying art. If someone watches this film and sees Swizz Beatz is collecting art, it may motivate them to want to go out and collect,” shares Pollard.

While as soon as black creatives struggled to interrupt into the mainstream, now museums are working to amass works and add black members to their boards. This pattern, nonetheless, isn’t completely novel. “This has happened more than once. It happened in the 1940s after the war. Then it went back to the normal disappearing act of black artists. Then it returned in the 1970s for a brief moment. People became interested in African American art because of the black power movement,” notes Wilson. “This current situation has gone much deeper than before. Every institution that I know is being very self-reflective. They are really trying to catch up.”

Pollard himself, who witnessed the first black cinematic wave, and is now seeing one other, is aware of the cyclical nature of illustration in the arts. “All of a sudden you had Boyz n the Hood, Straight Out of Brooklyn and Juice. And then we didn’t see it any more. But now it’s come back again. Now you’ve got Ava [DuVernay] and Regina [King],” he observes. “But I’m too cynical to believe that it’s just going to stabilize. It doesn’t work like that.”

In some methods, the documentary is just not solely a celebration of how far black artwork exhibitions have come since Driskell’s Two Centuries, it’s additionally an insurance coverage coverage in case this inclusive surroundings doesn’t stabilize. In case the wider world retracts into the acquainted sample of exclusion. And whereas there’ll at all times be incubators like the Studio Museum in Harlem, impartial black-owned galleries, and Barack and Michelle Obama’s placing portraits hanging in the National Portrait Gallery – the obligation remains to be incumbent upon conservationists like Driskell and Pollard to edify the already hard-won victories. “The only thing you had after the Two Centuries of Black American Art appeared at the museums in Los Angeles and toured in Dallas and Atlanta, and then came to Brooklyn, was the catalog,” explains Pollard. “Now you have not just a catalog, but a documentary that speaks to the lasting legacy of David Driskell and the importance of his work. And how it’s absolutely important now.”