Former Bank of England governor Mervyn King liked to compare the setting of interest rates to the dribbling of the late football legend Diego Maradona.

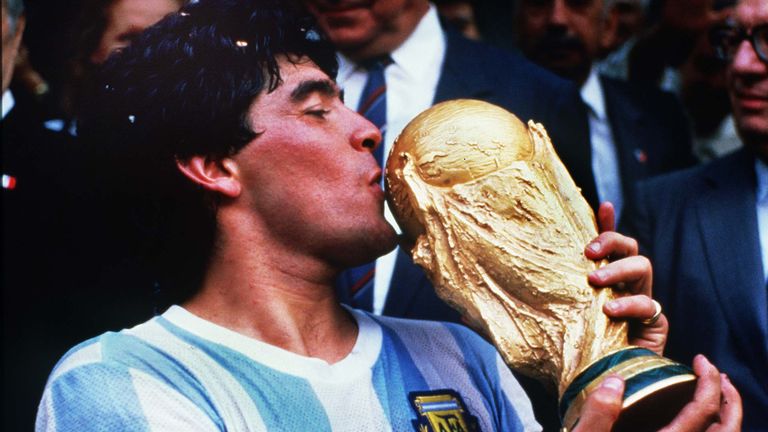

This wasn't just because he had a habit of inserting gratuitous sporting analogies into most of his speeches. Think of that famous Maradona goal in that infamous 1986 World Cup match against England - the one he scored with his feet rather than his hand.

In that second goal, frequently voted the best of all time, Maradona dribbled past much of the England team before slotting the ball past Peter Shilton. It was a virtuoso performance, but King noticed something interesting.

When you looked back at the replays what you saw was that far from dribbling around players, drawing a mazey line towards the goal, Maradona ran in nearly a straight line from the halfway line to the goal.

Far from dribbling around the England defenders, Maradona feinted this way and that while carrying on at precisely the same angle.

Central bankers, said King, do much the same thing.

Even when interest rates are left unchanged for long periods of time, the Bank's monetary policy committee (MPC) still had the power to influence spending and activity in the economy by feinting this way and that.

To put it another way, merely hinting that it might tighten monetary policy or loosen it could actually become a self-fulfilling prophecy, prompting households to respond as if the Bank had actually changed interest rates.

What then, is one to make of today's news from the Bank of England? Interest rates and monetary policy remained unchanged but, as we know from Maradona, that's not the whole story.

And the most striking bit of news today looks a lot like one of those feints: the announcement that Britain's banks should prepare to be able to implement negative interest rates within six months.

On the one hand this seems quite prudent: Bank rate is currently at 0.1%, which is already the lowest in its history. It cannot really get any lower without hitting zero or going below.

Negative rates - where banks theoretically pay customers to lend them money - are already in place in some areas of the world; it is only right to find out whether the financial system here could handle it. The Bank's conclusion is that it probably can.

But here's the thing: on the basis of the Bank's forecast, in six month's time the economy will be recovering rapidly from the current slump. In other words, it seems deeply unlikely that negative rates would be needed at that point. If anything, rates might need to be lifted.

Which brings us to the other interesting bit of footwork from the Bank today: it is also signalling that it might change its guidance about when people should expect a rise in interest rates.

Take a step back and this looks rather odd. On the one hand, the Bank is hinting we should be ready for rates to go below zero. On the other hand it is dropping a hint that we should be ready for rates to go up. Go figure.

In the event. Investors seemed to be most struck by the latter message than by the former.

In the minutes after the Bank's Monetary Policy Report was released, the pound strengthened - often a sign that traders are betting on higher borrowing costs in the future. In other words, what looks on the surface of it like a dovish signal, as economists might call it, looks a lot more hawkish.