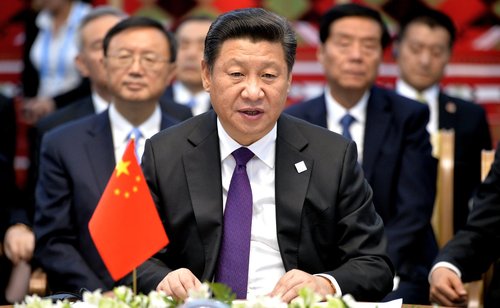

Perusing the day's news in their palatial homes, China's "communist" leaders must love to gloat about the bungles and misfortunes of their Western geopolitical foes. This month's storming of the US Capitol would have provided a few chuckles about the dysfunctionality of the world's proudest democracy. China's government-controlled reporters gleefully pen stories about the superiority of China's authoritarian system.

The Global Times was this week chiding US telecom authorities after the country's latest spectrum auction generated bids worth roughly $90 billion, nearly three years' worth of global investment in the radio access network (RAN). Europe also came in for censure. British operators have already shelled out £1.35 billion ($1.53 billion) for new 5G spectrum, noted the report. They now face another resource-sapping auction after the UK government rejected calls for a less costly giveaway.

Propaganda aside, the Chinese have a point. China's preferred system of handing out spectrum for a token fee has fueled a splurge on 5G infrastructure this year. Its operators have already erected as many as 700,000 5G basestations, dwarfing rollouts elsewhere. Thanks to all that activity, the global RAN market is likely to have grown 8% last year, said market-research firm Dell'Oro in a previous forecast. Take out China and sales would probably be flat.

RAN austerity

People who sell networks outside China feel aggrieved. Parallels have been drawn between the $90 billion sale in the US and the European 3G auctions that happened early this century, when telco resources went mainly for astronomical license fees rather than network investment. The clear risk is of a repeat in the pandemic-hit US. In a LinkedIn post, Sasha Javid, the chief operating officer of broadcast data network BitPath, said auction results "could result in slower buildout, high prices for consumers, less stock buybacks and missed targets for debt reduction."

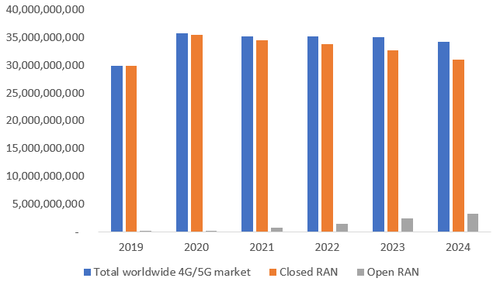

Competition in the US mobile market means operators are likely to prioritize capital expenditure over debt reduction, according to Fitch Ratings. But the outlook for companies that develop network equipment and products was already austere, despite the ongoing rollout of 5G. Based on Dell'Oro forecasts, Ericsson thinks the global RAN equipment market will show no growth between 2019 and 2024. Omdia, a sister company to Light Reading, reckons spending on 4G and 5G RAN products will drop from about $35.8 billion in 2020 to $34.2 billion in 2024.

One problem is that many operators outside China are in no desperate hurry to deploy 5G networks. Spectrum fees, falling data prices and teetering piles of debt are all constraints, while the absence yet of any 5G killer application is a disincentive. Meanwhile, most spending on 5G just replaces investment in older network technologies at the same mobile sites. Michael Trabbia, the chief technology officer of Orange, sees little need to build new ones.

All this explains why Ericsson and Nokia, the world's largest, non-Chinese equipment makers, are taking a run at the enterprise sector. Sales of network products to carmakers, energy firms and other industrial giants are rising. That has helped to compensate for a slowdown in the main addressable market. In the future, enterprise could be an even bigger deal.

But life for anyone in the mainstream telco market will be tough. Besides flat or dwindling sales, equipment companies are also being challenged by new rivals touting open RAN (O-RAN), a hyped technology that operators look determined to use despite lingering doubts. Orange has even gone as far as saying that any equipment it buys in Europe will have to be O-RAN-compliant starting in 2025. All of Europe's telco giants have been demanding O-RAN alternatives to Ericsson, Huawei and Nokia, the three dominant vendors of RAN equipment today. If O-RAN can perform as well as traditional RAN – something Orange expects by the mid-2020s – pricing pressure will grow.

The black hole of O-RAN

Anyone that stubbornly refuses to join the O-RAN program faces a shrinking market, according to Omdia. Its latest forecast, produced in November, anticipates a 13% decline in sales of 4G and 5G closed RAN products between 2020 and 2024. As nervy as they may be that O-RAN gives rise to new challengers, Ericsson and Nokia do not want to ignore their customers and risk missing out on future business. Both have joined the O-RAN Alliance, a group developing specifications, and promised O-RAN products. But China's Huawei has done neither, insisting O-RAN does not measure up. Right now, it has more pressing problems of a geopolitical nature.

While traditional revenues decline, Omdia expects O-RAN sales to soar over the forecast period, rising from about $252 million last year to around $3.2 billion in 2024. Yet this business may be contested by dozens of hardware and software firms. Altiostar, Mavenir and Parallel Wireless, three US companies, are the best-known software specialists today. But European operators want authorities to cultivate a local open RAN supply chain, ensuring Asian and US vendors are not the only alternatives to Ericsson and Nokia. All this could make for an extremely crowded $3.2 billion market.

Light Reading.

Barring the failure of O-RAN, the chief danger for upstarts is that operators stick with their usual vendors in the 5G era. Orange, for instance, has only just named Ericsson and Nokia as 5G suppliers in France. Over the next three years, its main priority will be to roll out a near-nationwide 5G network based on their traditional products. A major switch to other suppliers before the late 2020s is highly improbable. Far likelier is that O-RAN specialists will be restricted to new indoor deployments in factories or industrial parks. There could also be a role for network application developers. Introducing those would be easier with an O-RAN feature called the RAN intelligent controller (RIC).

Perhaps the biggest question is whether service providers will really embrace the "disaggregated" model they talk about so much. To avoid compatibility problems, operators usually buy all the RAN components for a particular site from the same vendor. With its new interfaces, O-RAN would allow a mash-up. But operating a network built by a legion of suppliers could be a management headache.

Howard Watson, BT's chief technology officer, is unconvinced. "It's unlikely that all of us will start deploying equipment from four or five different vendors because the operational challenge of the person in the van maintaining that tends to limit you to a choice of two," he told a recent committee of UK politicians. A market for the single- or dual-vendor open RAN could be an even harder one for a new entrant to crack.

Related posts:

- Orange issues 2025 O-RAN ultimatum to big kit vendors

- Europe's telco giants come together over open RAN

- UK love affair with open RAN goes on despite telco reservations

- Telefónica Deutschland wants Europe's COVID-19 funds for open RAN

- Open RAN might not save you much after all

— Iain Morris, International Editor, Light Reading