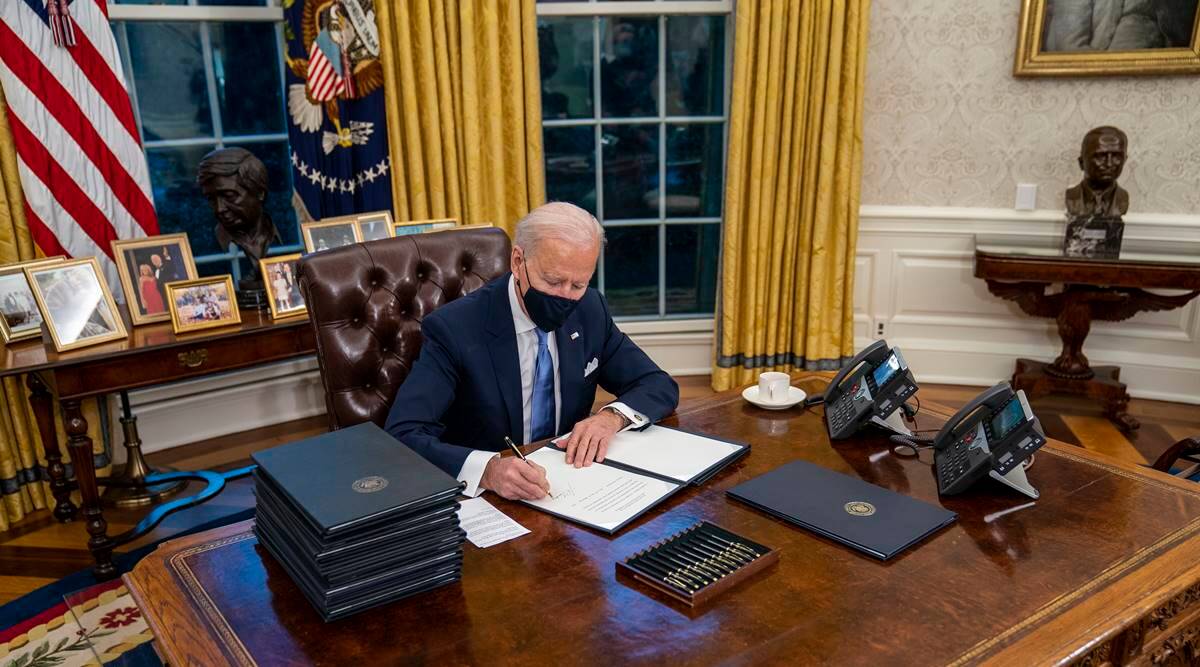

President Joe Biden signs executive orders during his first minutes in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, on Inauguration Day, Wednesday, Jan. 20, 2021. (Doug Mills/The New York Times)

President Joe Biden signs executive orders during his first minutes in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, on Inauguration Day, Wednesday, Jan. 20, 2021. (Doug Mills/The New York Times) Written by Lisa Lerer

As a child, Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. wrestled with words, grappling with a boyhood stutter. Years later, as a young politician, he could not stop saying them, quickly developing a reputation for long-winded remarks.

It was words that undercut his first two campaigns for the White House, with charges of plagiarism ending his 1988 bid and verbal missteps that hampered his 2008 outing from nearly the first moments.

Through a nearly half-century long political career marked by personal tragedy and forged in national upheaval, Biden’s struggle with his own words has remained a central fact of his professional life and of the ambition he harbored for nearly as long: the White House.

Yet Biden, the nation’s 46th president, has transformed himself into a steady hand who chooses words with extraordinary restraint.

The self-described “scrappy kid from Scranton,” Pennsylvania, who called former President Donald Trump a “clown,” refused to take the political bait laid by Trump for weeks after the election with his attempts to overturn the results. Rather than get sucked into the Trumpian chaos, Biden focused on announcing his Cabinet and helping his party win two runoff races in Georgia. And with a second impeachment trial looming in the Senate, Biden, 78, has maintained his steadfast faith in the political center, positioning himself as a champion of all Americans and a deal-maker between the left and the right.

His ability to steer and stay the course calmly through such turbulent times is a testament, say friends and family, to both Biden’s unabashed optimism and his deep belief in the importance of American political norms and traditions. The man who came to Washington at age 30 as one of the youngest senators in history now enters the White House as the oldest president in history, with more experience in government and legislating to guide his path than any leader in decades.

That Biden finds himself in this role at all is an unlikely turn of events for a man whose political career seemed to have stalled or ended so many times. But after 36 years in the chamber and eight years as vice president, he became a familiar figure in the country’s political consciousness.

To Biden’s friends and family, his success at winning the White House is proof that there is something fundamentally reassuring about his character — his loyalty, his empathy and his experience — that Americans want after four years of an unpredictable and chaotic administration. Even when he misspeaks, they argue, it underscores his authenticity, the journey of a man who moved through the darkness of the losses of his young wife, baby daughter and adult son to remain optimistic about politics, the country and his own destiny.

Throughout a long campaign, a global pandemic, a racial reckoning and a riot at the Capitol, Biden’s central message of moral and political restoration never wavered: Renew American decency. Return to good governance. And heal a divided nation.

While Biden has pivoted left with his party, he remains a centrist at his core, determined to unite a frayed body politic and persuade some Republicans to support his agenda. For much of the past half-century, Biden has found himself in the literal middle of American politics: in the central seat on the Judiciary Committee, in the center of policy debates in the Obama administration, at center stage in the presidential debates and now at the White House. He is a man both of and apart from Washington, deeply immersed in the mores, manners and maneuvering of the Capitol even as he spent decades commuting home to Delaware on Amtrak.

The political traits that would come to define Biden were present from the start. A Catholic son of Scranton and Wilmington, Delaware, he has long mythologized his childhood in stump speech tales of “Grandpop Finnegan” and virtuous sayings from his father, a car salesman who struggled to find work.

After being sworn in Vice President Kamala Harris gives Joe Biden a fist bump at the Capitol in Washington in Washington on Wednesday, Jan. 20, 2021. For many in an exhausted, divided nation, the inauguration was a sea change, not just a transition. (Ruth Fremson/The New York)

After being sworn in Vice President Kamala Harris gives Joe Biden a fist bump at the Capitol in Washington in Washington on Wednesday, Jan. 20, 2021. For many in an exhausted, divided nation, the inauguration was a sea change, not just a transition. (Ruth Fremson/The New York)

Even in the 1960s, Biden was something of an institutionalist in a blow-it-up generation. He rambled around the University of Delaware and Syracuse University College of Law with little connection to the civil rights movement and the other social activism of the time. Biden told reporters in 1987, “Other people marched. I ran for office.”

After marriage, graduation and a brief stint at a Wilmington law firm, Biden won a seat on the New Castle County Council. He entered the Senate in 1972 just weeks after the death of his wife Neilia and daughter Naomi in a crash with a tractor-trailer. Reeling from the tragedy, Biden would make only a six-month commitment to the Senate, taking the oath of office from the hospital bedside of his two young sons. He eventually found himself swept into the business of the body with a plum seat on the Foreign Relations Committee — an early move that would later cement his reputation as an expert in U.S. foreign policy.

His personal life stabilized after his marriage to his second wife, Jill, and the birth of a fourth child, their daughter Ashley. But his political career continued along an uneven course.

Joe Biden is sworn in as the 46th US President on Wednesday, Jan. 20, 2021, in Washington.(Saul Loeb/Pool Photo via AP)

Joe Biden is sworn in as the 46th US President on Wednesday, Jan. 20, 2021, in Washington.(Saul Loeb/Pool Photo via AP)

Biden’s greatest early failure and biggest success intertwined in 1987: the humiliation of a failed presidential bid and his victory as the new chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee in stopping Robert Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court. Biden announced his campaign was over during a break from the hearing, where his strategy focused on persuading Republicans to block President Ronald Reagan’s nominee.

As he progressed through what would ultimately be six terms in the Senate, Biden became known for his willingness to reach across the aisle to craft legislation like the Violence Against Women Act and the 1994 crime bill and as a crucial voice in U.S. conflicts overseas.

Another presidential bid in 2008 ended in failure. But his years on Capitol Hill and in foreign policy and his connection with white working-class voters later won him a place on former President Barack Obama’s presidential ticket.

In 2015, Biden mulled making a third bid for the White House, but the death of his son, Beau, from brain cancer that May was a devastating blow that Biden said left him emotionally unable to mount an effective campaign.

By the time Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in a surprise ceremony at the end of his second term, praising his vice president as a “lion of American history,” the event seemed to mark a tearful end to Biden’s political ambitions.

It was that faith in his own character and experience that persuaded Biden to make a third run at the White House. Five months before announcing his bid with a 3 1/2-minute video casting the election as a national emergency, Biden described himself as the “most qualified person” for the job. When confronted by a moderator with a list of his possible political liabilities, he dismissed them all as minor issues compared with the huge problems faced by the country.

“I am a gaffe machine, but my God, what a wonderful thing compared to a guy who can’t tell the truth,” he said during a stop on his book tour in 2018. “The question is, what kind of nation are we becoming?”