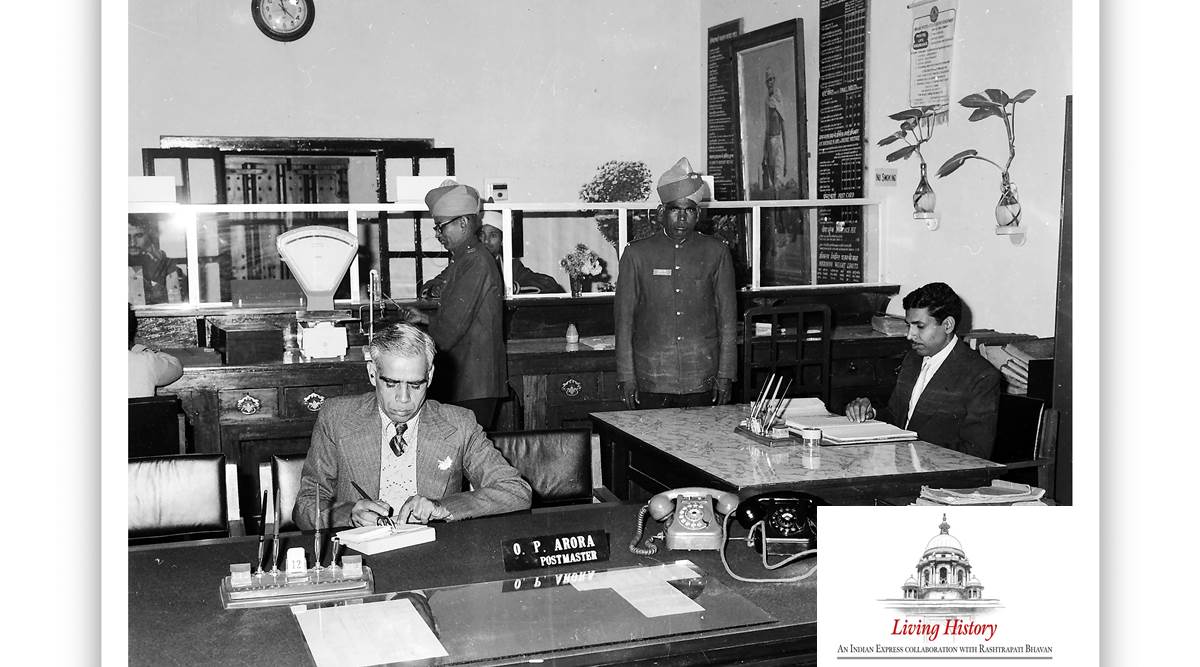

The Rashtrapati Bhavan Post Office in 1979. (Photo courtesy: Rashtrapati Bhavan)

The Rashtrapati Bhavan Post Office in 1979. (Photo courtesy: Rashtrapati Bhavan) By Jagannath Srinivasan

Even the most avid students of history may not have heard of Munshi Abdulla Khan, Babu WC Chakravarty, L Amarnath and Mathra Das. To allow these gentlemen to shimmer through the mists of time, one must step back to the Viceregal Lodge, Shimla, in 1904.

On July 24, 2014, the then President Pranab Mukherjee inaugurated a new post office in the President’s Estate, and tweeted: “The Rashtrapati Bhawan Post Office started as the Viceroys Camp Post Office in Shimla on 10.6.1904 and has historical records.” This statement was accompanied by a photograph of a note by the Postmaster, Shimla, in the Order Book of the Viceroys Camp Post Office (VCPO). It noted that the office was in good order, and that the first two letters received and stamped were for Lady Ampthill, wife of Lord Ampthill, Governor of Madras and acting Viceroy, and Major Strachey, Comptroller of the Household.

It is in this Order Book that those four gentlemen appear, as sub-postmasters and clerks of the VCPO. Since this was a touring post office, they travelled with all the paraphernalia between Calcutta, Shimla and Delhi, catering to the communication needs of the Viceroys. They came in for praise from the inspecting officers for the “good order” of the post office. An entry from 1932 records, “This office opened in 1904, has had a good career, free from any fraud and with but few irregularities.” In 1927, the inspecting officer states, “I have no doubt that Babu Woomacharan Chakravati Sub Postmaster, takes a keen interest in his work, and appears to be the correct man in the correct place, as he has an abundance of common sense and intelligence.” In his reply, the sub-postmaster writes, “I feel thankful to note that, at your first visit of my office, you have been able to carry a happy impression with you, and I am glad to mention that my co-partner, Babu Mathra Das, can be a co-sharer in the credit that you may give for this office working.”

Apart from Chakravarty’s work ethics, what these records also reveal is the importance of the post office for the Viceroy. Until 1854, postal service was a chaotic medley, with varying rules and postage rates in different provinces. Regular mails were available between a few important centres, and the district collectors were responsible for their local post-offices, with a senior military officer being postmaster for cantonments. The postal reforms in Britain, with the introduction of the “Penny Post” (uniform postage across the country), hadn’t been replicated in India. Lord Bentinck made initial attempts, but it was Lord Dalhousie who in 1854, established the Imperial Postal Department under a Director General. In the midst of the Anglo-Sikh War in 1848, he had written from Ambala to the Governor of the North-Western Provinces (NWP) to replicate the English system of a unified post office. The expansion of the railway network also made the task easier.

You’ve Got Mail: The Rashtrapati Bhavan Post Office now (Photo courtesy: Rashtrapati Bhavan)

You’ve Got Mail: The Rashtrapati Bhavan Post Office now (Photo courtesy: Rashtrapati Bhavan)

The strategic importance of the post office was made apparent in 1857. The British army in India was then deficient in two key areas, intelligence and transport. But the postmasters were able to provide information on the spread of the revolt, especially where there were no telegraph lines. A highly organised horse transport and bullock trains, part of the postal network, aided the army in troop movements and evacuation of the wounded and the refugees, including the successful transport of ladies and children of Lucknow to Calcutta, after the siege was broken by Sir Colin Campbell.

The VCPO was so important for the viceroys that the military secretary in 1920 ruled that only the best officials with at least 10 years of service be posted there. The Record Book in its early days attests the importance of the Viceroy’s mail. An order of 1910 directed the “Town Inspector of Post Offices to convey the foreign mails of the Viceroy to the VCPO by hired rickshaw (kept ready beforehand for that purpose) and to convey his outward mails under receipt to the Overseer on the Kalka Shimla Train.” Multiple entries recording the inspector’s receipt of the “Viceroy’s Secret Bags” appear in the Order Book. The importance of efficient delivery of mails within the Viceroy’s Camp is attested in Babu WC Chakravarty’s request for efficient postmen in view of the irregularities committed by the temporary postmen attached from the local post office when he was on tour.

The telegraph, proven indispensable in 1857, continued to gain importance. A 1909 order gave preference in promotion to officials trained to operate the telegraph. The VCPO had a telephone and the Record Book notes an exchange about whether the police could use it free of cost.

The post office did not renounce its peripatetic nature even on shifting with the Viceroy to Delhi. In 1935, for example, it was in Calcutta in January, Delhi in March and Shimla in May. Finally it settled in the Viceroy’s Estate, and services beyond the mail and money orders started appearing. The Deputy Postmaster General, Panjab and NWP, in 1937 educated the staff on life insurance and asked them to ensure availability of “Bijoya” telegram forms. As Indians started opening savings bank accounts, there are references to translating addresses from the “vernacular”.

In 1947, it was rechristened the Governor General’s Camp PO, and soon reflected new realities. An inspection report mentions Mohammad Alam, sub-postmaster, who opted for Pakistan and was relieved on August 9. Even during the chaos of Partition, it continued to provide “exemplary” services, and the private secretary to the Governor General expressed pleasure on the neatness of the office. After a brief appearance as the President’s Camp PO, in 1950 it became the Rashtrapati Bhavan Post Office, and ceased annual pilgrimages to Shimla. The RBPO is now a service provider for the head of state of democratic India, and the residents of the President’s Estate.

(Jagannath Srinivasan is Officer on Special Duty in the President’s Secretariat)