This extreme global price volatility can be seen across farm commodities. (Representational)

This extreme global price volatility can be seen across farm commodities. (Representational) First, it was the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) that, on December 4, revised downwards its GDP de-growth projection for 2020-21 from 9.5% to 7.5%. On Thursday, the National Statistical Office (NSO) pegged the current fiscal’s GDP growth at minus 7.7%. The figure was even better, at minus 7.2%, after netting out taxes and subsidies on products.

These official estimates — along with data pertaining to the purchasing managers’ index, electricity and fuel consumption, goods and services tax collection, Google mobility index and other high-frequency indicators — confirm one thing: The extent of negative growth induced by Covid-19 and the lockdown hasn’t been as much as was initially feared.

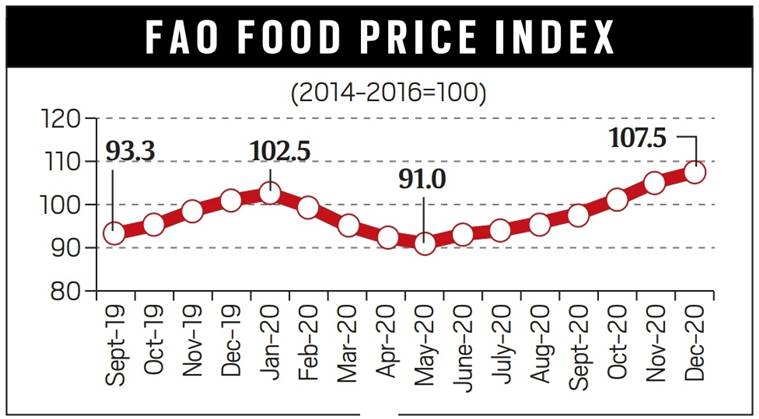

Food and Agriculture Organisation’s food price index highest since 2014.

Food and Agriculture Organisation’s food price index highest since 2014.

The NSO’s first advance estimates suggest that the Indian economy may even register a small 0.3% year-on-year growth in the second half (October-March), after contracting minus 14.9% in the first half (April-September) of 2020-21.

But this relative optimism on growth — economic activity seems inching towards its pre-pandemic levels — is tempered by an emerging challenge: food inflation.

This also makes it difficult for the RBI to further cut interest rates or even continue with its accommodative monetary policy stance.

The NSO’s GDP data came the same day the UN Food and Agriculture Organization released its latest Food Price Index (FPI) number for December. This index – reflecting international prices of a basket of food commodities against a base year (2014-16) value of 100 – averaged 107.5 points for the month. It was the highest since November 2014.

What is significant is how the FPI has soared since May 2020 (see chart). From falling to a four-year low of 91 points then, it has hit a more than six-year high in December.

This extreme global price volatility can be seen across farm commodities.

Wheat, corn and soyabean prices at the Chicago Board of Trade exchange (for the most actively-traded futures contracts there) are ruling at $6.42, $4.94 and $13.55 per bushel, respectively, as against their corresponding year-ago levels of $5.50, $3.84 and $9.44. The price of raw sugar futures traded at the Intercontinental Exchange has similarly gone up from 13.59 cents to 15.60 cents a pound in the last one year. So has crude palm oil from 3,042 to 3,817 ringgit per tonne at Kuala Lumpur’s Bursa Malaysia Derivatives exchange.

Export prices of rice (Thai white grain with 5% broken content) and cotton (the benchmark Cotlook A index of Far East landed rates) are also higher compared to a year back: $512 versus $418 per tonne and 86.55 cents versus 78.75 cents per pound, respectively.

Skim milk powder prices at Global Dairy Trade, the fortnightly auction platform of New Zealand’s Fonterra Cooperative, averaged $3,044 per tonne on January 5. That is a steep jump from $2,373 eight months ago.

There are three main reasons for international agri-commodity prices firming up in the past few months.

The first is a steady normalisation of demand as most countries, including India, have unlocked their economies after May. Even as demand has gradually recovered, restoration of supply chains post-Covid is taking time. Dry weather in major producing countries such as Thailand, Brazil, Argentina and Ukraine, plus a shortage of shipping containers, has only aggravated the supply-demand imbalances.

The second reason is stockpiling by China, which has stepped up imports of everything – from corn, wheat, soyabean and barley to sugar and milk powder – to build strategic food reserves amid rising geopolitical tensions and pandemic uncertainties. Last month, the country published a new draft law taking into account “new situations and questions” posing severe challenges to its “grains stockpile security”.

The third reason may have to do the ultra-low global interest rates and floodgates of liquidity opened by major central banks. This money, which has already flowed into equity markets, could well find a home next in agri-commodities – more so, in a scenario of tightening world supplies.

Household inflation expectations in India have traditionally been shaped by food and fuel prices. Retail prices of petrol and diesel in Delhi have, since last year, moved from Rs 75.74 and Rs 68.79 to Rs 84.20 and Rs 74.38 per litre, respectively. Annual consumer food price inflation stood at 9.43% in November. That number, more than GDP growth, is the one worth tracking in the months ahead.