Inside the archive museum.

Inside the archive museum. An eyewitness account of Maratha king Chhatrapati Shivaji’s “humiliation” in Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s court; Maratha king Sambhaji’s eloquent Sanskrit letters to Mughal mansabadar (vassal) Ram Singh on why he had foregone Mughal riches; Mirza Raja Jai Singh’s leave application to Aurangzeb; Shah Jahan’s farmaan (royal edicts) to his Rajput mansabdaars for uninterrupted supply of Rajasthan marble for the Taj Mahal; Amber king Jai Singh’s attempt to woo businesses with a bait of tax rebates; and a courtesan’s letter interspersed with 108 idioms to a Jodhpur king.

These are some snatches of little-known histories running into 1.4 crore pages that have been dusted off, digitised and microfilmed by the Rajasthan Archives Department. These archives running into 40 crore pages cover a period from 1623 to the British India and include census reports, land revenue records, administrative orders, account books, cartography, copper plates and most importantly 327 Mughal farmaans in Persian.

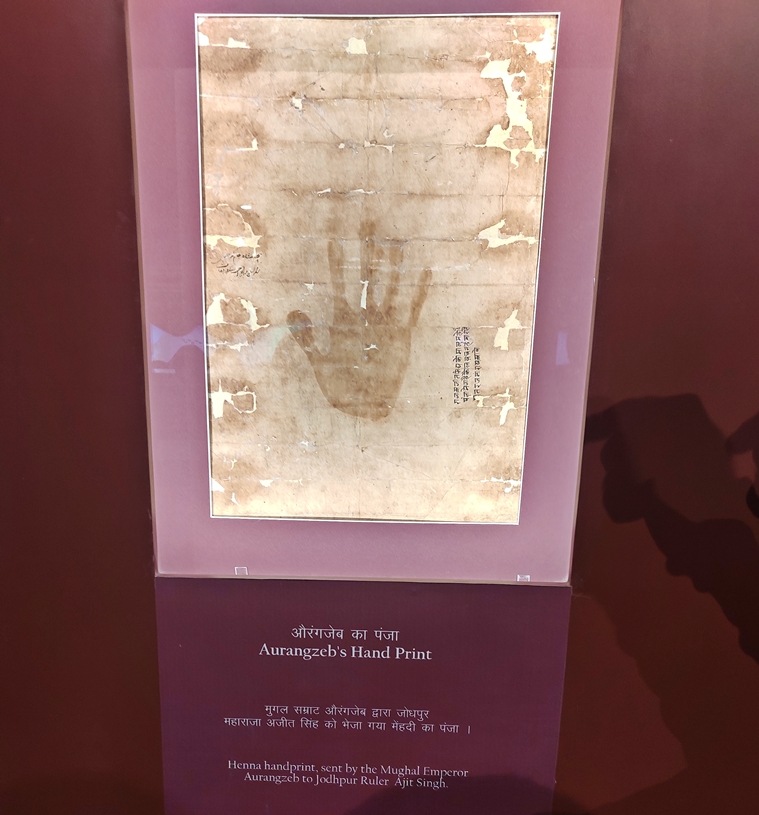

Aurangzeb’s hand print

Aurangzeb’s hand print

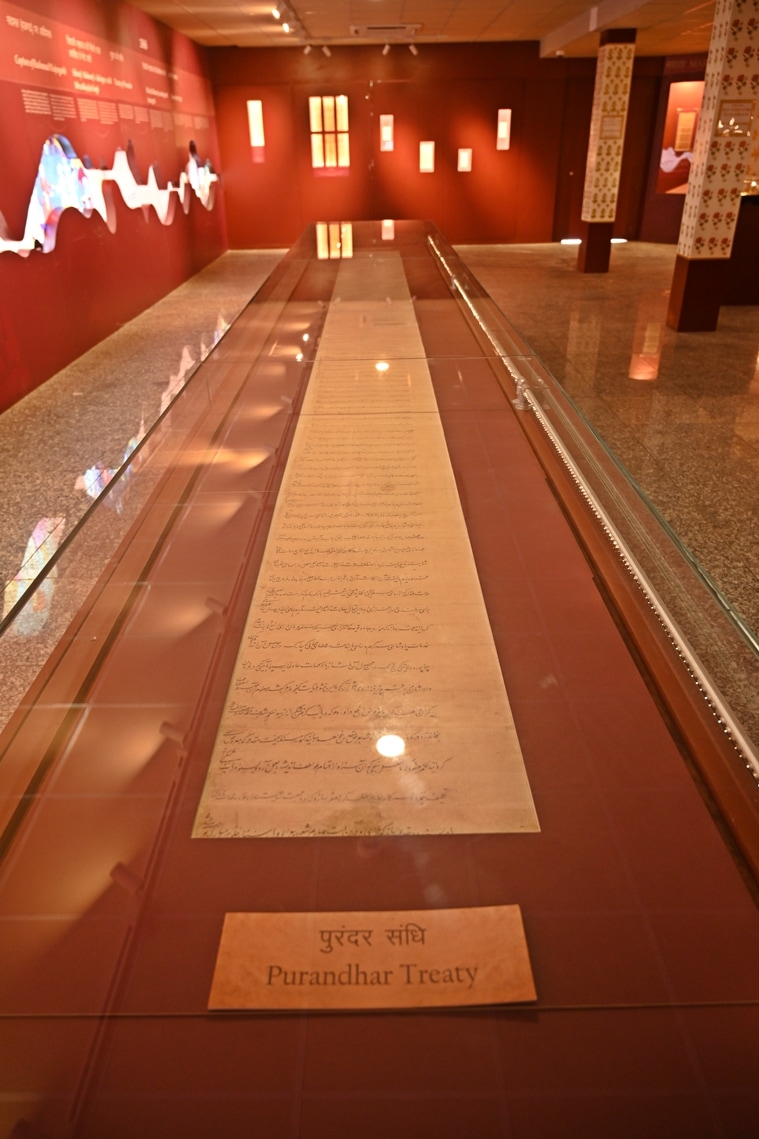

Some of these farmaans resplendent with gold and floral prints, copper plates and the Treaty of Purandar (between Mughal mansabdaar Jai Singh I and Chhatrapati Shivaji) are displayed at museum galleries in the department’s Bikaner headquarters. Copper plates of Mewar tell the tale of economic and political churn of the 16th century. One of them notes Maharana Pratap’s beneficent gesture to donate land and cattle to Brahmins after the Battle of Haldighati with Mughal Emperor Akbar’s forces.

“The digitisation project aims to unlock a vast knowledge about the Mughal-Rajput and Rajput-Maratha ties for the public. Few know that Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s son Akbar accused him of a latent Hindu bias. Such vignettes can reveal more insights and give new perspective to our medieval and contemporary histories,” says Mahendra Khadgawat, director of the department.

Of the four crore archival pages selected for digitisation, the department has put over 1.4 crore online at a cost Rs 2.5 crore.

A copy of the Treaty of Purandhar.

A copy of the Treaty of Purandhar.

The journey to digitise centuries-old fragile pages was arduous if not insurmountable, recalls Khadgawat. It all started in 2005 when the department’s Bikaner headquarters started digitising land deeds dating back to the 1600s. “We have digitised around 20 lakh of archival land deeds. We have set up a kiosk which can be used to locate land deeds. We issue a copy of the ownership title within a day after an applicant fills up requisite forms. Before digitisation, it would usually take four to six months to secure ownership documents,” he says.

Buoyed by such a response, the department turned to its archives. In 2013, under a pilot project, 35 lakh pages were digitised. “In that year, we were perhaps the first government department to digitise archives on such a large scale. We had to acquire hands-on experience and learnt minute details about digitisation and microfilming. For example, we learnt that overhead scanners were better suited for such an exercise compared to flatbed or auto-feeder scanners,” says Khadgawat.

A view of the stake room.

A view of the stake room.

“We have indexed the subjects on our website. The website has 100-200 visitors daily compared to in-person 100 visitors annually in the pre-digitisation period,” he says.

Other states and foreign universities have taken note of the feat.

The Comptroller and Auditor General of Indian has recently lauded the state archives department’s project and sought its help for digitising “records relating to pension and GPF (General Provident Fund)”. Before this, UP and Haryana auditing departments had shown interest in emulating the Rajasthan model. Far from home, Khadgawat was invited by the University of Exeter and the University of Pennsylvania to share his experience.

Besides the archives department, Rajasthan oriental research institutes and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Arabic Persian Research Institute in Tonk are opening their vaults of centuries-old wisdom in the form of manuscripts, folklores and encyclopaedic knowledge on botany and zoology, says Mugdha Sinha, Secretary of Arts and Culture Department, Rajasthan.

“The state government has taken a conscientious step to preserve, digitise and microfilm our rich heritage especially in terms of archival records written in various languages… Once researchers translate these works into language readable to the public, this knowledge can be shared across Indian and the world,” she says.

According to her, the first step towards digitisation was taken in 2008 when the then Finance Commission set aside funds for the same. It was followed by regular budgetary allocations by the state government.