Ganesh Prasad, 52, earns a living through his small kirana store in Bakutagam village, on the border of the Ganjam and Khorda districts in Odisha. Life in Bakutagam remained normal until June: Prasad’s shop was open and he was able to run his business. Things began to change, however, as migrant workers from the village began to return. The Central government had been running Shramik special trains to ferry these migrant workers, who were out of work and stuck in big cities.

This region of Odisha, despite its paddy cultivation, handlooms, beaches and the famous Chilika lake, remains backward. Thousands of people migrate to faraway States such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka in search of work.

When they returned, the migrant workers also brought with them the dreaded coronavirus. The two districts of Khorda and Ganjam alone contributed about 558 or close to one-third of the 1,829 deaths in Odisha.

Prasad — and people like him — is highly vulnerable to the infection given his age and the nature of his livelihood. The infection eventually reached the family — what followed was utter misery, as they found that getting healthcare wasn’t just an emotionally draining experience, but one that pushed them into a poverty and debt trap as well.

The path to poverty

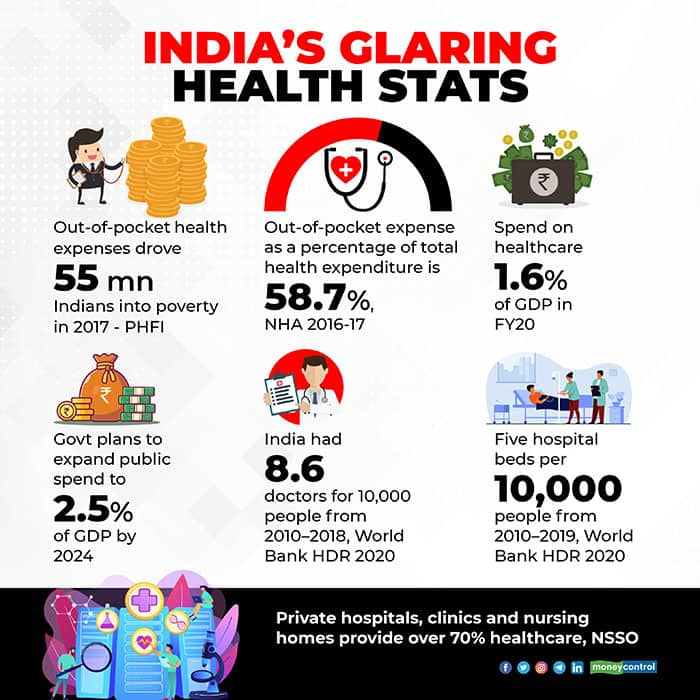

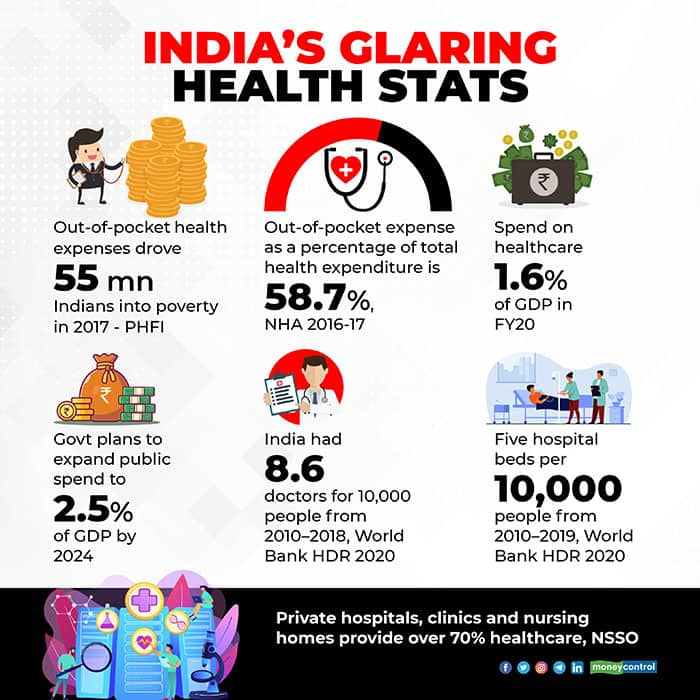

Despite State and Central health insurance schemes, and a vast network of government hospitals, out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure remains one of the biggest reasons for people falling into poverty. The Covid-19 pandemic made matters worse for thousands of families.

A 2018 study by the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) has estimated that out-of-pocket health expenses drove 55 million Indians into poverty in 2017.

As per the National Health Accounts (NHA) 2016-17, Out of Pocket Expenditure (OPE) as a percentage of total health expenditure is 58.7 percent. There was a small decline from the highs of 64.2 percent in 2013-14, but it still remains one of the highest.

With a few exceptions such as AIIMS–Delhi, government hospitals have been on the path of deterioration due to chronic underfunding, shortage of doctors and nurses, a lack of state-of-the-art medical equipment, hygiene and accountability, as well as corruption.

A system in decline

The Central government’s spend on healthcare amounted to 1.6 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in FY20. The government said it plans to expand the public spend to 2.5 percent of GDP by 2024.

The supply-demand imbalance of doctors and hospital beds in India is quite stark. According to the latest World Bank Human Development Report (2020), India had 8.6 doctors for 10,000 people from 2010–2018, and five hospital beds per 10,000 people from 2010–2019. In terms of bed availability India ranks 155th among 167 countries.

Meanwhile, governments have slowly shifted gears from being providers to payers of care. In addition, the rise of health insurance has led to the expansion of private hospitals and diagnostic chains. The National Sample Survey Office’s 71st round data shows that private hospitals, clinics and nursing homes provide over 70 percent of healthcare in India.

The trust in government hospitals has been eroded further by most politicians and bureaucrats getting treatment in private hospitals. But private care, especially corporate hospitals, is unaffordable for most Indians.

The pandemic has exposed the faultiness of the Indian healthcare system. So far, close to one crore Indians have tested positive for the Covid-19 infection and about 1.5 lakh have died.

Moneycontrol spoke to some of the affected families, lawyers, hospital executives and health activists to find out what ails the system. It also saw copies of PILs, bills, and discharge summaries of the people.

Chasing impoverishment

One day, Prasad felt feverish and had chills. He took common fever pills for a couple of days but the fever persisted. He was taken to a nearby primary health centre, where he was diagnosed as having typhoid. Prasad was given medication but his condition deteriorated. He stopped eating and had difficulty in breathing. The family took him to Balugaon government hospital in Khordha district, which was closest to their village.

Prasad’s oxygen level had dipped to an alarming level of 76 and he was having symptoms of pneumonia. The hospital asked them to immediately take him to Bhubaneswar, the largest city and the capital of Odisha, where much of the state’s health infrastructure is based.

Prasad’s elder son Babul Supriyo Sahoo, 25, hired an ambulance, and took his father to Capital Hospital in Bhubaneswar, nearly 100 km away. He was told there were no beds available. From Bhubaneswar he took his father to SCB Medical College and Hospital in Cuttack, about 30 km away, but couldn’t find a bed there either. He returned to Bhubaneswar, and his search for a bed took him to SUM Hospital, Care Hospital, Vivekananda Hospital, AMRI and Apollo Hospitals. Everywhere the stock answer was: “No beds.” Meanwhile the oxygen cylinders in the ambulance were exhausted, and time was running out for Prasad.

Prasad’s son Babul said they decided to return to Berhampur, the headquarters of Ganjam district. They finally got a bed in the Covid ward at the government’s MKCG Hospital. Prasad underwent a Covid-19 test but his report came back negative. The hospital authorities asked the family to shift Prasad to a non-Covid ward. The staff at the non-Covid ward refused to give him a bed. Despite testing negative, Prasad’s condition didn’t improve.

To get him better treatment, the family decided to shift Prasad to Visakhapatnam, the closest other big city with decent health infrastructure, but still 280 kilometres away in Andhra Pradesh State. But Visakhapatnam, too, had been battered by Covid-19, especially during September and October, and was facing an acute shortage of beds.

When they got to Visakhapatnam, Babul took Prasad to Seven Hills Hospital. Immediately an HRCT (high-resolution computed tomography) scan was carried out, and they were told Prasad’s Covid was at CORADS-5 level. CORADS is an assessment system to measure the level of Covid-19 involvement in the lungs and CORADS-5 is the highest level of risk assessment for Covid-related pneumonia.

Seven Hills, however, told Babul that its ICU beds were full. Once again the chase for a bed began. The hospital would first ask for a deposit of Rs 1 lakh. Babul said he even sold his mobile to pay for the ambulance charges.

In Visakhapatnam, he shifted his father to three private hospitals, including Apollo Hospitals. Babul said that by the time he was admitted to Apollo, his father’s condition had stabilised, but the family had run out of money. So, Prasad was shifted to the government’s King George Hospital (KGH). At KGH, Prasad made a good recovery and was discharged.

Babul says the family has spent about Rs 7 lakh, of which it borrowed Rs 4 lakh. With interest he says it has now become Rs 5 lakh. The remaining money was arranged by relatives, friends and others.

Covid, laments Babul, has turned the clock back for the family.

Overcharging

State governments that are aware of the ground realities of unaffordability of Covid care in private hospitals have resorted to capping the charges for treatment and diagnostics. But there are still huge gaps in implementation, and enough loopholes for exploitation.

In July, K Lakshmi Narasamma, 65, from Chintal, a working class neighbourhood in Hyderabad surrounded by an industrial cluster, began suffering body pain and fatigue, which progressively worsened.

Her family rushed her to a nearby nursing home. At night her pulse dropped and she complained of breathlessness. The nursing home didn’t have oxygen support, and asked the family to take her to a hospital that had such a facility.

Thus began the family’s nightmarish ordeal. Narasamma’s kin began calling hospitals to see if there was a bed available to admit her. After calling at least a dozen hospitals, and using whatever connections they had, one private hospital, 25 kilometres away, agreed to offer a bed.

But when they got Narasamma to the hospital, the authorities there said the patient needed ICU care and that they did not have any vacant ICU beds. The family once again had to make frantic calls. To their relief another private hospital, closer home, agreed to admit her, but with conditions.

The hospital asked the family to deposit Rs 5 lakh, and Rs 50,000 per day. Given the urgency of the situation, the family paid Rs 4 lakh, and admitted the patient. Soon her swab samples were taken, and an RT-PCR test confirmed it as Covid-19.

“After four days of her admission, we got a call from the billing section. They told us the deposited money is exhausted and demanded we pay another Rs 1 lakh. We weren’t given any provisional bill, so we really didn’t have any idea for what they were charging,” said Sai Balaji, nephew of Narasamma, who was dealing with the hospital.

On the tenth day, the family decided to shift the patient, as they had run out of money. Balaji said the years of savings pooled to buy a house were used-up in paying the hospital.

The hospital’s total bill came to around Rs 6,70,000.

In its discharge summary, the hospital wrote that the patient was classified as CORADS-3, a mid-level risk assessment as per the HRCT scan. Narasamma was kept on Bipap or non-invasive ventilation.

“Patient needs hospital stay, but attenders are not willing for further hospital stay. So patient being discharged,” the summary sheet read.

The family shifted Narasamma to the government’s Gandhi Hospital on August 8. She died later that day.

During this time her nephew Balaji came to know that the Telangana government had capped the rates of Covid-19 treatment in June. When he compared the Telangana government rates to the rates charged by the hospital, Balaji said he found discrepancies and the hospital flouting Telangana government price-cap norms.

The Telangana government capped ICU isolation with ventilator at Rs 9,000 per day, which included monitoring and investigations such as CBC, Urine routine, HIV spot, Anti HCV, HbsAg, Serum Creatinine, USG, 2D ECHO, drugs, consultation, bed charges, meals, procedures such as Ryle’s tube insertion and urinary tract catheterisation. He found that the hospital was charging Rs 33,000 per day. It created several subheads for this purpose. For instance it is charging Rs 7,000 per day as ICU isolation care and charging separately for ventilators.

The biggest surprise for Balaji was the hospital charging Rs 12,000 per day on PPE kits. Balaji alleges that he was overcharged even on medicines and consumables.

Balaji took to microblogging site Twitter to draw attention to the hospital’s actions. The Telangana government responded and deputed an official, Dr G Srinivasa Rao, to conduct an inquiry into the allegations. But Balaji says nothing happened thereafter. What makes matters complicated is that the hospital is owned by a politician from the TRS, the party ruling the State.

With not much happening from the government side, Balaji filed a writ petition in the Telangana High Court, making the Telangana government, Union Health Ministry and the hospital respondents.

Balaji told Moneycontrol that he has been getting calls from the hospital for talks but is determined to seek justice in the court.

Insurance is not enough

Talha Abdul Rahman, a Delhi-based advocate, has taken up the case of a Covid-19 patient. Rahman says that his client’s father was hospitalised and passed away with Covid-19 complications at a large corporate hospital in Delhi.

“My client’s father was covered by medical insurance up to Rs 5 lakh. He was admitted to a large private hospital in Delhi. The hospital tried experimental drugs on him but he succumbed. In the end my client got a bill of Rs 9 lakh.

He was in for a shock as the insurance company paid less than Rs 2 lakh of the bill, asserting that it would only pay in accordance with the capped rates of the Delhi government. “The rates the private hospital charged my client were rack rates, and not the Delhi government-capped charges. The hospital says that the price cap does not apply to patients who subscribe to insurance as a mode of payment,” said Rahman.

“I wrote to the Insurance Regulatory Development Authority (IRDA) seeking clarity, but am yet to get any response from them,” he added.

Rahman says there was confusion, as the Delhi government has asked private hospitals to reserve 40 percent of their beds for Covid-19 patients. Later it capped the Covid treatment charges for 60 percent of beds in hospitals.

So, if a private hospital has dedicated 100 percent of its beds to Covid-19 patients, it can charge rack rates for 40 percent of the beds. There is a substantial price difference and many patients did not understand this. Rahman alleges that private hospitals would say that 60 percent of their beds were full, but there was no way to verify this. It was found that people who could afford to pay and are politically connected were getting beds.

Symptoms of a larger malaise

Dr Alok Roy, Chair, FICCI health Services Committee, and Chairman of Kolkata-based Medica Superspecialty Hospital, disagrees with the argument that private healthcare is responsible for the impoverishment of people. He also refutes allegations of overcharging.

“The rates for Covid care have been very restrained and well controlled from the private sector. The government has opened multiple Covid care centres and people can go there; they don’t have to come to private hospitals. Today, every State government has its own hospitals, which are capable of treating patients,” he said.

Roy added: “It’s not that Covid requires 2,000 medicines; four-five medicines are enough. The best part: 80-85 percent of people require nothing. So, only 5 percent require admission, and these are distributed among both government and private hospitals. Where is the pressure on people?”

Roy added that there isn’t any profiteering as claimed by numerous people.

“Doctors are expensive. Nothing is manufactured in India, and we import everything (equipment). The cost of medicines, the government controls. Government charges 18 percent GST on everything I purchase. If the bill is 5 lakh, 1 lakh is the government’s take. We operate on 10 percent EBITDA; PAT is 4 percent. Healthcare is not a profit game, it’s a valuation game,” Roy added.

The costs incurred by healthcare providers have jumped by at least 20 percent following Covid-19, he asserted.

Rajendra Patankar, CEO of Pune-based Jupiter Hospitals, says one cannot generalise about private healthcare using a few cases. “It is always the patient’s choice to take services from a private hospital,” he pointed out.

“Patients have the right to know the tentative estimate of the services they wish to avail before making the decision,” he added. Patankar denies use of strong-arm tactics with patients. He says private hospitals actually “end up losing many times, as patients don’t pay or honour payments.”

But health activists say that the above cited cases are not exceptions. “Overcharging and flouting of rules is rampant across the hospital industry. The individual cases are mere glimpses of the much larger corruption and dishonesty in corporate healthcare. These stories are definitely a hallmark of the Covid era,” says Malini Aisola, Co-Convenor, All India Drugs Action Network (AIDAN).

Aisola says that the argument that people have a choice between public and private healthcare isn’t true. “Over the period (since the Covid outbreak), many patients were pushed towards private healthcare due to a range of factors. For example, stoppage of non-Covid services in government hospitals that were converted to Covid designated hospitals or unavailability of beds,” Malini says.

"For families with elderly or critical patients, there was often a mistrust in Government services. Public confidence suffers when politicians and bureaucrats make a beeline for prominent private hospitals for their treatment,” she adds.

AIDAN, along with Jan Swasthya Abhiyan (JSA), has intervened on the civil society side in a public interest litigation (PIL) filed by advocate Sachin Jain, which is seeking a directive regulating the cost of Covid treatment at private hospitals. NatHealth, AHPI and General Insurance Council have impleaded themselves in the case.

(This is the first in a series of reports on hospitals. The second report will look at how private hospitals have performed during Covid-19)

_2020091018165303jzv.jpg)