On December 17, 2010, a young Tunisian who sold vegetables set himself on fire in front of the governor’s office in the central Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid to protest police harassment. Mohamed Bouazizi’s was not the first self-immolation in the region, or even in Tunisia, yet it sparked a rage never seen before. Nor was his story caught on camera — but it went viral nonetheless.

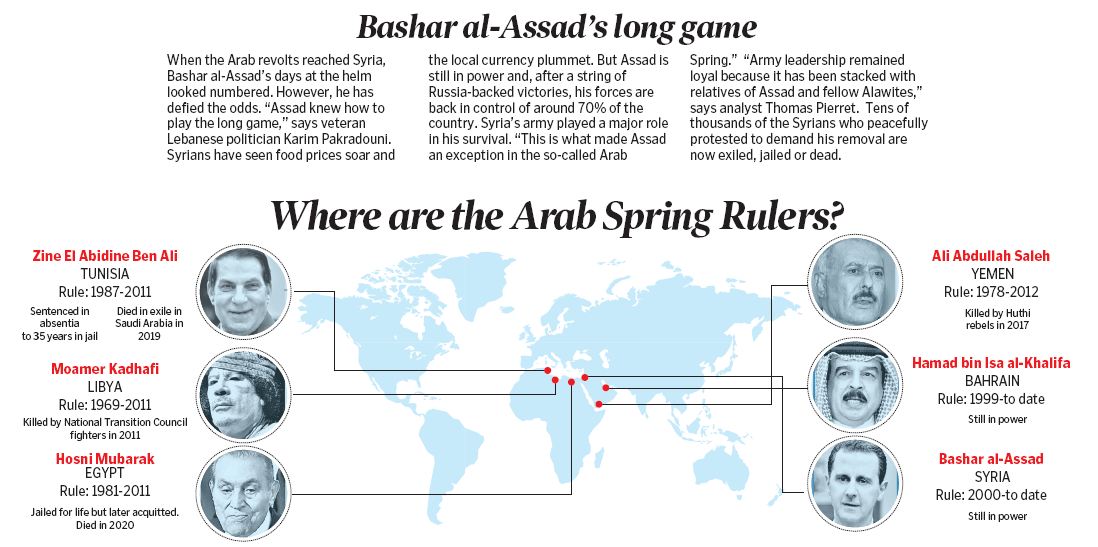

By the time Bouazizi died of his wounds on January 4, the protest movement against President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who had been in power for 23 years, had spread to the entire country. Ben Ali’s 23-year rule ended 10 days later when he fled to Saudi Arabia, becoming the first leader of an Arab nation to be pushed out by popular protest.

The spirit of the “Jasmine Revolution” spread. Within weeks, pro-democracy protests broke out in Egypt, Libya and Yemen. When the rage spilled into the streets of Cairo, the region’s largest city and its historical political crucible, the contagion earned its “Arab Spring” moniker. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in Egypt to demand the removal of Hosni Mubarak, president since 1981.

“Look at the streets of Egypt tonight; this is what hope looks like,” celebrated Egyptian author Ahdaf Soueif wrote in The Guardian then. On February 11, as more than a million took to the streets, Mubarak resigned. The voice of the people was rising across the region, toppling some of the most entrenched dictatorships.

One sentence became the slogan as the Arab Spring rippled across the region: “Al-shaab yureed isqat al-nizam” — Arabic for “The people want the downfall of the regime”. A new paradigm was being born in the Middle East with the realisation that its tyrants were not ten foot tall and that change could come from within.

Besides Ben Ali and Mubarak, Libya’s Moamer Kadhafi, Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh and Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir (1990–2012) were the other significant scalps claimed by the Arab revolutions. The five of them combined a whopping 146 years of rule, not counting Saleh’s 12 years as president of North Yemen before the country’s unification in 1990.

Arab Winter?

The term ‘Arab Spring’, which started first appearing in late January 2011, is now seldom used in the Arab countries — where the words uprising and revolution are preferred — and has since been criticised as a misnomer. Noah Feldman’s 2019 book on the subject is titled Arab Winter, a catchphrase that started being used almost immediately after the phrase ‘Arab Spring’ caught on. In a cover blurb for the book, prominent academic Michael Ignatieff says it highlights “one of the most important events of our time: the tragic failure of the Arab Spring”.

The vacuum created by the downfall of reviled regimes was not filled by the democratic reforms protesters called for, instead in many cases turmoil ensued. In Egypt, a brief and exhilarating experience in self-rule was soon soured by brutal police repression. In 2012, Egyptians elected Mohammed Morsi, an Islamist whose programme was met with fierce opposition from part of the protest camp, paving the way for a 2013 coup by the defence minister. Retired general Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is still in power today and his rule is arguably more autocratic than Mubarak’s ever was.

In Bahrain, the only Gulf monarchy to experience mass protests, the uprising was brutally quashed with the help of Saudi Arabia, which preempted any revolutionary inclinations on its own soil with massive cash handouts. Protests in civil war-scarred Algeria did not catch on, those in Morocco were doused with cosmetic reforms and repression through courts. Libya’s erstwhile revolutionaries split into myriad militias that fragmented the country and Yemen slid into a sectarian-fueled civil conflict.

But the place where the Arab Spring died was Syria. Few of the region’s leaders seemed more difficult to unseat than Bashar al-Assad when 2011 started, but within weeks of the first protests, the writing was on the wall for the former London-based ophthalmologist. Literally. “Your turn, doctor.” The words, inspired by the undoing of Ben Ali and Mubarak, were spray-painted on a wall in the southern town of Daraa. The teenagers guilty of such lese-majeste were swiftly detained and tortured, prompting a wave of angry protests that sparked a nationwide uprising. Assad’s turn never came however.

With the exception of Tunisia where there is now a fragile democracy, each of the revolution countries collapsed in their own way. As protest movements were brutally repressed and sectarian hatred ignited, jihadists — in Syria and elsewhere — found fertile ground. “It didn’t take long for the protesters’ non-violent ethos to flicker out in the battle zones of Libya, Syria, and Yemen,” author Robert F Worth writes in A Rage for Order.

“Under the convenient cover of street protests — where they could travel without being recognised — the jihadists were suddenly watching the collapse of the state in all three countries.” Their growth culminated with the 2014 proclamation by the Islamic State group of a “caliphate” roughly the size of Britain straddling Syria and Iraq.

The ultra-violence that IS craftily propagated on social media and the group’s ability to attract thousands of fighters from Europe and beyond instilled a fear in the West that wiped out the early pro-democracy enthusiasm. The world’s focus shifted to the fight against terrorism and away from the removal of autocratic regimes, which quickly recast themselves as the last rampart against Islamic extremism.

The West, led by the US administration of Barack Obama, failed to see the Arab revolts coming, initially voicing support for protesters. But they stopped short of direct intervention, with the exception of the controversial Nato-led raids which dislodged Kadhafi in Libya.

A decade on, one would be hard-pressed to look at the Arab revolts as a success. The conflict in Syria has left the country in ruins and triggered the worst human displacement since World War II. In Yemen, children are starving to death, and Libya has turned into a lawless and fragmented battleground for militias and their foreign sponsors, in which democratic aspirations have been buried deep.

Springing Again?

The popular protests that erupted a decade ago were followed by disappointing reforms at best, dictatorial backlash or all-out conflict at worst. Yet the spirit of the revolts is far from dead, as evidenced by the second wave of uprisings that caught on in Sudan, Algeria, Iraq and Lebanon eight years later. Something “in the fabric of reality itself” has changed since then, says Lina Mounzer, a Lebanese author whose family has roots in both Egypt and Syria. “I don’t know that there is anything more moving or noble than a people demanding a life of dignity in a single voice,” she adds. “It proves that such a thing is possible, that people can revolt against the worst despots, that there is enough courage in people standing and working together to face down entire armies.”

“The emergence of the 2019 wave of the uprisings in Algeria, Sudan, Lebanon and Iraq showed that the Arab Spring did not die,” says Asef Bayat, an expert on revolutions in the Arab world. The countries swept up by the latest revolts had initially stood on the sidelines as a contagion of uprisings gripped Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, Libya and Yemen in 2011.

“The main drivers of the Arab Spring… continue to bubble under the surface of Arab politics,” points out Arshin Adib-Moghaddam, a professor at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. “2011 yielded 2019 and 2019 will merge into a new wave of protests,” says the author of the book On the Arab Revolts and the Iranian Revolution: Power and Resistance Today.

The trauma of the civil war (1992-2002) “prevented the Algerians from going out in the streets” in major protests, says Zaki Hannache, a 33-year-old activist. But on February 22, 2019, fear gave way to anger as President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s plans to run for a fifth term after 20 years in power prompted demonstrations in key cities. The uprising, later become known as the Hirak protest movement. The Algerian army, like its counterparts in Tunisia and Egypt, withdrew its support for the regime, causing Bouteflika to resign on April 2, 2019. One of the most important Arab Spring lessons, Hannache says, came from Syria. “We learnt that the only option was to keep the movement peaceful”.

The 2003 US invasion had long rid Iraq of dictator Saddam Hussein by the time the Arab protests started toppling seeming invincible regimes like dominoes. “We saw the Arab Spring uprisings as an opportunity to rescue democracy in Iraq,” says Ali Abdulkhaleq, a 34-year-old activist. Protests broke out again almost every other year, but anger finally boiled over in October 2019. An unprecedented nationwide uprising demanding a complete political overhaul forced the government of then-prime minister Adel Abdul Mahdi to resign.

The clearest indication of the “influence of the Arab Spring uprisings” on Sudan came in 2013. People took to the streets against skyrocketing petrol prices, revealing the revolutionary fervour brewing beneath Sudan’s surface. Protests broke out again five years later over soaring food prices and continued into 2019. On April 11, 2019, the army announced it had put Bashir under house arrest. Military and protest leaders signed a “constitutional declaration” in August and a sovereign council was formed for power-sharing before transition to civilian rule.

Lebanon saw a wave of protests in 2015 over a garbage management crisis. It culminated in October 2019, when a government decision to tax WhatsApp calls sparked an unprecedented nationwide movement demanding the wholesale removal of the ruling elite. The movement took aim at the entire political class, forcing the government of then-prime minister Saad Hariri to bow to street pressure. A year on, Hariri looks set to return as premier.

For Imad Bazzi, a Lebanese activist and advocacy expert, who had organised the first series of protests, the episode marked the third chapter of a revolutionary process that started in 2011. “It’s a continuous thing. The waves come one after the other and they are all connected.”

Arab Spring Effect

The Egyptian author Ahdaf Soueif argues it is still too early to tell what its legacy will be and that the revolts are still a work in progress. “The conditions under which people had lived from the mid-70s onwards led to revolt. It was unavoidable. It continues to be unavoidable,” she says.

“The people of the region set a new yardstick for the politics and governance that they demand. Since then, all politics has been measured against those demands,” stresses Professor Arshin Adib-Moghaddam. “The core demands of the protests are still bubbling under the surface and will boil over at the next opportunity like a political tsunami…any state that doesn’t understand this new reality is bound to be confronted,” he says.

Lina Mounzer, who has lived through Lebanon’s revolt in 2019, concurs that whatever comes next, the way people view their leaders and perhaps more importantly themselves has been durably affected. “We have lived so long in a world that has tried to instill in us the idea that communitarian thinking is suspect and that individualism is synonymous with freedom. It’s not. Dignity is synonymous with freedom…This is what the Arab Spring, not only taught us, but confirmed… What we do with that lesson — bury it or build on it — is something that remains to be seen.”

Now you can get handpicked stories from Telangana Today on Telegram everyday. Click the link to subscribe.

Click to follow Telangana Today Facebook page and Twitter .