American Airlines' Market Losses Will Aid Competitors' Recoveries

The covid-19 financial crisis facing airlines will result in significant market changes.

American Airlines has financially underperformed in a number of key markets for many years.

While many airlines will benefit from American's weakness, some airlines will benefit more than others.

As covid-19 continues to negatively impact the airline industry, significant long-term strategic changes are becoming apparent at multiple carriers. Even in the best of times, not all markets and routes performed as strongly as others and major crises like covid-19 lays bare those parts of airline route systems that did not perform well before covid-19 and likely will be smaller parts of those networks as the industry recovers.

American Airlines (AAL) execs have given indications on multiple occasions regarding financially underperforming parts of its network, some of which can be verified in their filings with regulators. I have written several Seeking Alpha articles highlighting the negative financial impact some parts of American’s network have had on the company for a number of years. The American – USAirways merger seven years ago was intended to compete with earlier mergers between Delta/Northwest and United/Continental which allowed them to become some of the largest global carriers and yet American’s merger has not produced either the financial benefits and large portions of its network have continued to underperformed financially, according to data which American provides to the U.S. DOT.

As I have noted in previous articles, American has lost billions of dollars trying to develop its own route system in the Asia-Pacific region. In Europe, American has lagged Delta (DAL) and United (UAL) on flights to The Continent, leaving American with just breakeven earnings across the Atlantic even in the last five years, which were some of the industry’s best before the covid era. Domestically, American management has indicated for several years that some of its hubs are much stronger financial performers, indirectly saying that some of its hubs operated at breakeven levels of profitability. The company said prior to covid that the focus of its network would be Dallas/Ft. worth (its largest hub and headquarters), Charlotte, and Washington National airports. It is by far the largest airline at all of those airports. It has indicated that its hubs in New York City (both LaGuardia and JFK airports), Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles are financially weak.

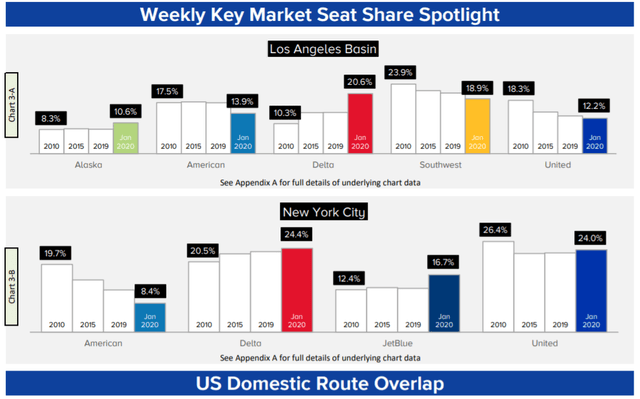

American’s flight schedules for the winter of 2021 highlight that it is cutting capacity in several of the cities where it has previously indicated weakness. New York City’s quarantine and lockdown requirements have decimated travel demand for all carriers but American’s capacity cuts in NYC are 15-20 percentage points deeper than other carriers at the same airports. At Los Angeles, American was the largest carrier prior to covid but has cut capacity much deeper than any of the other big 4 carriers. At its Chicago and Philadelphia hubs, American is operating flights to its non-hub cities on certain days each week, or rather, its Chicago and Philadelphia hubs are only hubs on certain days of the week. No other carrier has cut as deeply as American in so many of its largest cities and it is very unlikely that American will be able to restore its capacity in each of these markets when demand begins to return to the industry.

Airline blogger Cranky Flier and Visual Approach have recently teamed up to produce the Cranky Network Weekly, a new, subscription-based, in-depth analysis of airline schedules including the changes that are released each week. The December 6th edition of their report includes this insightful summary that will support our discussion.

American’s Financial Situation

AAL was the lowest margin U.S. airline in 2019 and in several years prior to that with a 2019 net income margin of 3.7% compared to over 10% for Southwest (LUV) and Delta . AAL’s debt is the highest in the industry and AAL spent over $1 billion on interest expense in 2019, multiples of times higher than any other airline. Since the pandemic began, AAL has consistently had the industry’s highest cash burn and that distinction does not appear to have an end in sight with fourth quarter cash burn guidance near $30 million/day. AAL has the most amount of debt and the U.S. Treasury now holds approximately $10 billion in AAL assets as collateral for debt AAL has taken on through the CARES Act. In contrast, Delta and Southwest did not accept Treasury loans under the second phase of the CARES Act, instead placing debt in the private capital markets.

Why are American Hubs Underperforming?

In order to understand the reasons that American’s hubs are in the condition they are in today, we need to peel back twenty years of airline history. American’s financial performance has not been comparable to its legacy/global airline peers for much of the past 20 years – or since 9/11. American engaged in an acquisition of TWA’s assets just before 9/11 and was saddled with not only adapting to the enormous economic changes of 9/11 but also attempted to salvage what had value from TWA and absorb it in into American’s network. In 2003, American attempted an out-court-restructuring instead of filing for chapter 11 bankruptcy as United had already done but AAL did not gain most of the benefits that other airlines gained through chapter 11. As most of the legacy airlines later filed for chapter 11 and then merged with other airlines, American’s costs grew even more uncompetitive through the 2009 financial crisis until they finally filed for chapter 11 in 2011. American’s chapter 11 process was intended to allow American to emerge as a standalone carrier but USAirways’ Doug Parker convinced creditors, with the support of employees at both airlines, that a merged American and USAirways would provide a greater likelihood of success than an American standalone plan. Delta and Northwest kicked off the megamerger cycle several years before American emerged from bankruptcy and merged with USAirways. American’s cost advantage from chapter 11 lasted less than two years; despite being the product of the most recent large U.S. airline merger, American’s unit costs were already the industry’s highest prior to covid. As the covid era began, American had no choice but to start cutting its least-profitable routes with the entire future of hubs at stake even if AAL has yet acknowledged that it is closing hubs.

In order to win the support of labor for the merger, Doug Parker did not make the necessary labor costs, including reducing the size of the merged workforce, to give American a chance to be cost-competitive with nimbler Delta and United. As a consequence, American could not cut the underperforming and duplicated routes that each carrier brought to the merger. American is the only one of the big 3 global carriers that did not close any hubs prior to covid.

American’s high unit costs were most apparent in highly competitive markets such as New York City and Los Angeles, ironically the markets that American most needed to win in to compete with Delta and United. While airlines don’t report profit margins by hub, average fare data is available and it is very likely that American’s New York and Los Angeles hubs became some of its biggest financial drains. A series of missteps in each of those two cities put American at a distinct disadvantage on top of its own cost issues. In New York, American could have been a much larger airline if USAirways had not engaged in a slot swap with Delta that traded one-quarter of the slots at LaGuardia airport for a much smaller amount at Washington National where USAirways was already the largest carrier with a majority of the slots. Delta was already the largest carrier at JFK airport in New York but became the largest carrier at LaGuardia as well with the slot deal, although it did not have a majority of slots at either airport. Ironically, American and USAirways were required to divest slots at Washington National as part of their merger roughly equal to the number of slots that USAirways gained from Delta in the slot deal. Not only had USAirways traded away valuable assets that allowed Delta to dramatically grow in New York City but the slot deal set USAirways up to be unable to grow any larger at Washington National due to competitive concerns from the DOJ, eliminating any benefit of the merger at Washington National.

American had made many of its own strategic errors in New York prior to the merger. It had never done well in continental Europe while Delta and United grew stronger in that region in part due to their continental European joint venture partners. Since the merger, American has suspended a number of destinations from New York and moved them to other hubs, including Philadelphia, attempting to find a niche where it could compete to Europe; yet, the New York market is critical to negotiated business and American was increasingly forced to fly routes that were likely not profitable in order to keep corporate accounts.

Domestically, the transcontinental routes from JFK to Los Angeles and San Francisco were problematic for American before the merger despite being backbones of its historic route system. The early 767s that American used on those routes were configured with a high proportion of premium seats and proportionately low numbers of economy seats, making American’s unit costs ever higher on aircraft that already had high unit costs. As low-cost carriers with a focus on discounted premium cabin services such as Virgin America took larger shares of the transcon market, American decided to replace its older 767s with new A321s, still with a large percentage of premium seats but eliminating a large portion of the coach cabin seats, a formula that by itself would have pushed American’s unit costs on its transcontinental A321s (designated A321Ts) to the top of the industry. However, shortly after American launched its A321T strategy, JetBlue added its Mint premium cabin product on its A321s in a strategy that had a far lower number of premium seats than American but priced at an aggressive discount while retaining essentially the same number of economy seats that JBLU had on its smaller A320 aircraft without Mint cabins. In the transcon markets, American’s unit costs rose even as average fares fell providing a drag not just on the New York end of the routes but also in California.

Like Delta, American has historically obtained fairly equal points of sale on its transcon services at both ends of the route, in contrast to United which has west coast strength and JBLU which is stronger on the east coast. American tried to leverage its position in the transcon markets (among the largest in the country) to grow into other markets, including Asia. Post-merger, American engaged in an aggressive build up of flights from Los Angeles to Japan, China, Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand, as well as to Argentina and Brazil. Even before covid, American execs began to disassemble their Los Angeles to Asia network due to low fares and American’s inability to compete with Delta and United, both of which had multiple western U.S. gateways to Asia. American also had to compete with Asian carriers which, like Delta and United, have multiple west coast gateways to Asia while American poured all of its efforts into LAX.

As the covid era arrived, American had no choice but to dramatically cut the largest money-losing routes from both New York and Los Angeles, including reducing service between the two cities more than its competitors, making the dozens of other routes to other cities from those hubs much less valuable. At LAX, American is now flying approximately two-thirds of the capacity that Delta, previously the second largest airline at LAX, is now flying. At both JFK and LGA in NYC, American has cut its capacity more aggressively than other carriers, including Delta at both airports and JBLU at JFK.

American Airlines new terminal at New York LaGuardia source: AAL

American Airlines new terminal at New York LaGuardia source: AAL

In Los Angeles, it made the decision to exit its Beijing route. By July 2020, American decided to end its Los Angeles to Shanghai flight and request that it be transferred to Seattle. American has proven that it does not do well in highly competitive markets; although American was the only U.S. airline that flew LAX to Beijing, both Delta and United also flew LAX to Shanghai, making the route one of the flew that the big 3 U.S. global carriers all served in addition to foreign competition. American’s average fares on those two LAX to China routes were well below DAL and UAL on identical or comparable routes.

New Partnerships

In pinning its hopes on building a presence in Seattle as well as restructuring its shrinking operations at Los Angeles and New York City, AAL turned to two smaller airlines to help gain something from its market exits. American has had a codesharing/marketing arrangement with Alaska Airlines (ALK) for a number of years and reduced it after the American/USAirways merger. Now, American wants to make Seattle as its west coast gateway to Asia even though Delta has its second largest Pacific gateway in Seattle and also has build enough domestic service to have 70% of the local Seattle market revenue that ALK has (ALK is headquartered in Seattle) and half of ALK’s local passenger share. AAL’s plan is to use ALK flights to help provide connecting passengers to AAL’s new Pacific flights (currently proposed to be Shanghai and Bangalore, India).

In NYC, AAL has developed a marketing and codesharing plan with JetBlue (JBLU) which is the second largest carrier at JFK, smaller than Delta but larger than American. American proposes to use JBLU to feed AAL transatlantic flights which could potentially grow by a dozen new flights. Unlike on the west coast, JFK and LaGuardia airports are slot-controlled and both AAL and JBLU have indicated they would like to be able to swap slots at the two airports, although neither airline has provided details for slot swaps or trades which might require DOJ approval. JBLU presumably could operate from LaGuardia to Florida more profitably than American but JBLU has a very small pool of LGA slots.

Both the ALK and JBLU marketing transactions are problematic in several respects. First, AAL would still have a smaller presence than now and to competitors in the local market (either Seattle, Los Angeles, or NYC), making it even less likely than now for customers to choose American. Very few international routes are operated from non-hub cities and yet American is essentially proposing to have no (or a very small) local hub from JFK, LAX or Seattle. In addition, American’s plan to use a partner airline to deliver connecting passengers bumps against the reality that the fare that is allocated to the domestic portion of a longhaul international trip is fairly small since fares are usually allocated based on the distance of each segment necessary to get a passenger from his origin to his destination. Global airlines that operate their own domestic and longhaul international service use their position in the local market as well as the system value of an international passenger to help justify the low portion of the fare that is carried on the domestic flight. In a joint venture, a U.S. airline might connect a passenger to a foreign joint venture partner but the two then split the total revenue – but that model doesn’t exist outside of joint ventures which AAL cannot have with ALK or JBLU. Further, JBLU and ALK both have a long list of foreign codeshare partners so they have to balance the demand for passengers by American along with their other partners, all while maximizing their revenue, usually by maximizing the number of their own local market passengers. Domestic codeshare arrangements have existed between U.S. airlines and rarely have resulted in significant benefits to the larger carrier.

In fact, ALK and JBLU are most likely to benefit simply by AAL leaving markets which they have each served competitive with American. However, AAL’s dual choice of ALK and JBLU – each on separate sides of the U.S. – raises the conflicts of interest that AAL has in partnering with two different domestic airlines which are competitors to each other as they are to AAL. ALK’s transcon network has lost significant ground since its merger with Virgin America, in part because ALK chose not to equip any of its fleet with the lie-flat premium product which has become the norm in the transcon market. UAL, JBLU and DAL have been the beneficiaries of ALK’s smaller transcon network. ALK has also tried to split its NYC presence between all three NYC airports, badly fragmenting its presence in markets where it is outclassed by larger airlines. AAL has indicated that it will partner with JBLU on the JFK transcons, choosing the stronger of the two in that market segment but potentially leading to a further deterioration of ALK’s position. Not to be relegated just to the east coast and transcons, JBLU has recently announced or started a number of new routes from Los Angeles, in some cases directly competing with ALK. JBLU recently closed its largest west coast base at Long Beach, gained gate space at LAX, and wants to grow LAX into a focus city even though it will still be one of the smallest carriers in the S. California market even if it succeeds at all of the routes it has indicated it will fly. AAL’s plans to salvage its own position in two of the largest markets is already leading to incursions between both of its two partners which are only certain to grow.

As the largest current player at both NYC airports where AAL has significant operations as well as at LAX, Delta stands to gain the most. In both cities, AAL and DAL fly (or flew) many of the same markets so AAL’s suspension of service leaves Delta in the position of being the only legacy carrier in many markets. Destinations such as Austin, New Orleans, Nashville and Orlando all saw both American and Delta service but only have Delta service now. In the three major airports of New York City, based on current schedules, Delta offers more than 24% of seats, the highest share in the market, while American’s share has fallen the most over the past 10 years, even before the covid era. Perhaps more interesting is the fact that DAL has become the largest carrier in the Los Angeles basin, not just displacing American at LAX but also LUV which offered scores of high frequency flights which do not work in the current era. Even if LUV returns a percentage of its short-haul, high frequency capacity, DAL’s gains from AAL’s reduced service in NYC and LAX are likely to be permanent.

United is jockeying to get a larger percentage of the NYC market, in part due to AAL’s weakness as well as because of more than a dozen new JBLU routes from Newark, UAL’s largest operation in the NYC area. United has stated for years that they wanted to return to JFK airport but could not obtain gates and slots. It has now obtained both and will serve the Los Angeles and San Francisco markets using a premium heavy-configured 767 which will add hundreds of premium cabin seats/day to a market where there is little premium demand. Like AAL, UAL’s aircraft configuration will have high unit costs making it hard to believe that they, like AAL, can be successful against both Delta and JetBlue which use more densely configured aircraft which seem more appropriate but esp. in the current environment.

Compounding the changes in competitive dynamics in some of the country’s top markets is uncertainty not just about how much business travel will return when most perceive it safe to travel but also how many people have moved out of high cost, high tax cities including New York City Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area. Corporate travel policies that have been released indicate a long recovery for business-related travel esp. from some of the top travel markets. Oversupply in some of the historically large business markets is certain to persist, making it harder for the financially weakest carriers to defend their markets.

Given American’s weak financial condition as well as its size – only slightly smaller than Delta in terms of 2019 revenues – other carriers stand to gain potentially billions of dollars in 2019 revenues at AAL’s expense. NYC and LAX each represented about 7-8% of AAL’s system revenues which amounted to more than $40 billion. In an industry where recovery will be determined by every new long-term passenger won from a competitor, the competition to win over passengers that AAL likely will no longer carry will be intense. It is not unreasonable to believe that ALK DAL and JBLU could see 3% or more additional system revenue just in the New York and Los Angeles markets. Because AAL’s global attractiveness will be reduced as it reduces its presence in top markets, DAL and UAL could gain in other markets at AAL’s expense. Because American and Delta’s domestic route systems more closely compete with each other, Delta has the potential to gain an even larger share of American’s revenue. Add in that Delta and Southwest are both adding Miami service which have the potential to further weaken American’s presence in Miami and the amount of AAL revenue at stake is higher than ever.

source: Routes Online

source: Routes Online

AAL valuation

Seeking Alpha contributor Matthew Zeets recently looked at AAL’s enterprise value in order to derive a stock valuation for the company in this engaging article Avoid American Airlines: A Study Of Enterprise Value And The Nature Of Leverage (NASDAQ:AAL). Matthew arrives at an $11 price target for AAL in 2022 while acknowledging that he can’t accurately predict some factors that could drive AAL’s share performance such as the rate of return of business travel or the competitive environment, which some readers addressed in the comments section.

In fact, it is certain that AAL is far more likely to be a net loser competitively in the next few years not just in NYC and the LA Basin but also in its other competitive hubs including Chicago, Miami, and perhaps Phoenix. AAL and UAL both are facing the same heightened degree of competitive capacity additions that will make recovery more difficult. Unlike AAL, UAL has a much larger cash cushion and appears to be doing a better job of reducing costs in the covid era.

Many investors continue to lump AAL DAL and UAL into the same group and expect similar types of financial outcomes for each even though the competitive and financial outlooks for each of those three is very different.

Matthew Zeets’ PT for AAL might be generous; if revenue recovery sips for another several months – which is very likely – AAL will be simply digging a deeper hole from which it must emerge, regardless of government aid or not.

The competitive environment in the U.S. airline industry is intense and will only increase as demand returns. American Airlines is unique in the industry in its financial fragility and the negative competitive environment that is unfolding in many of AAL’s top markets including AAL’s reduced presence in the NYC and Los Angeles area.

Disclosure: I am/we are long DAL, LUV. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.