MANILA, Philippines — Chinese workers employed by local offshore gaming firms never left despite some of these companies closing shop when the pandemic struck.

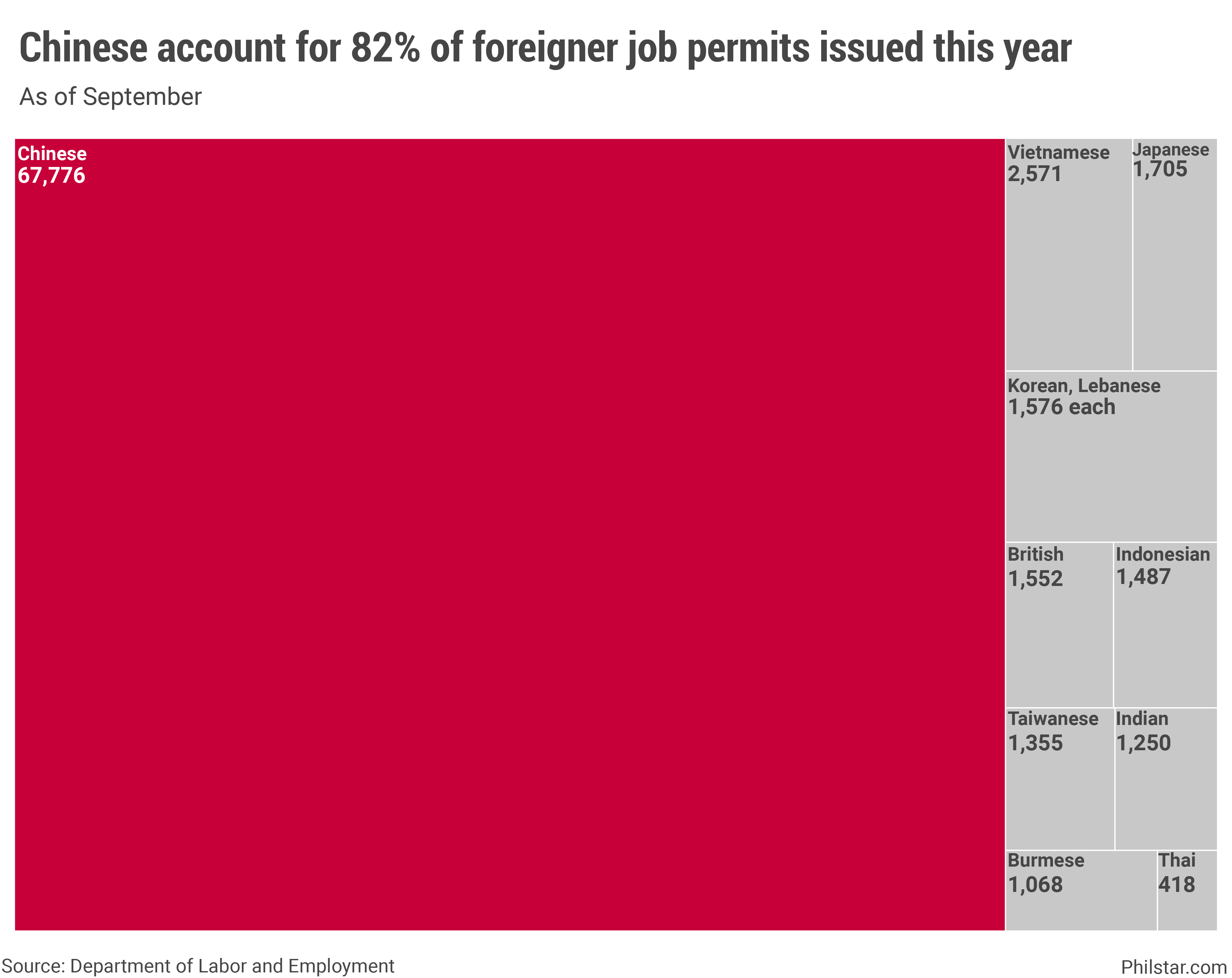

Their decision to stay, in turn, kept the labor department issuing alien employment permits (AEP) to foreign workers even at the height of lockdowns. From January to September, 83,204 AEPs had been issued, inching up from 83,057 same period a year ago, 82.2% of which went to Chinese nationals.

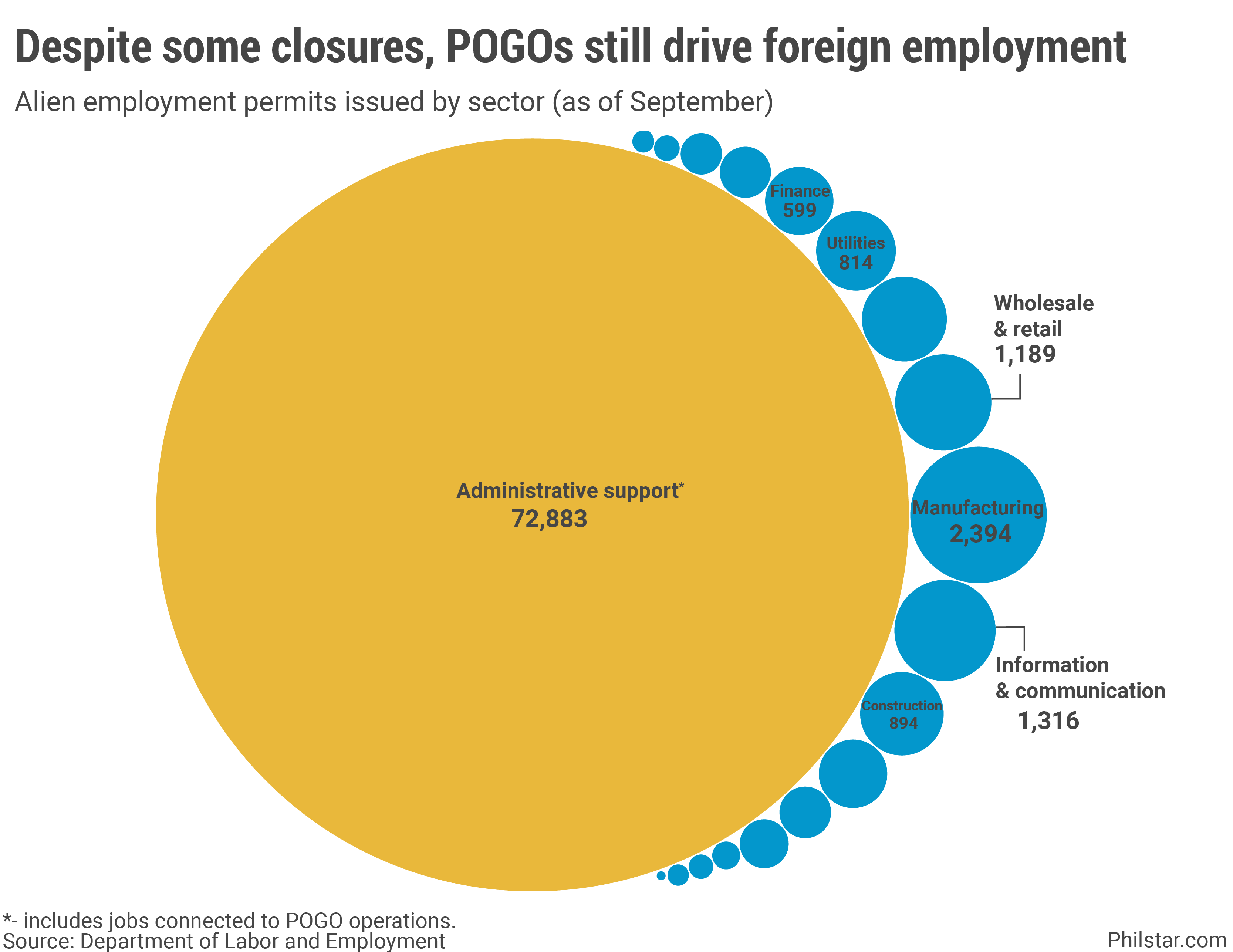

By sector, a huge chunk of workers with fresh AEPs were employed under “administrative and support service activities” at 72,883, a segment that Labor Assistant Secretary Dominique Rubia-Tutay said included workers in Philippine offshore gaming operators (POGOs).

“To us, it’s (number of AEPs) not high. If you look at it in our overall employment situation, it’s less than 1% (of total jobs)…,” Tutay said in a phone interview.

“But these are regular employment of foreign nationals allowed under existing law and policies of the Philippines,” she added.

A number of factors help explain the current rise in Chinese workers while POGOs are reportedly shutting down. One of which is the likelihood AEPs were applied months ago when restrictions were still not enforced, and only approved thereafter, Tutay said.

POGOs also did not entirely leave the Philippines. As per gaming regulator’s data, 36 of 55 accredited POGO operators were permitted to resume operations as of November. The number increases to 152, albeit down from 338 before the pandemic struck when other services critical to POGOs are considered, including IT systems used for betting that also employed people.

“No Filipinos can take the job in operation of POGOs,” Tutay said.

“POGO operations (are) mainly driven also by Chinese players, which (are) offshore. And then the programs being developed are also in Chinese, so the characters, the programming, the IT, these are all in Chinese,” she explained.

Under the Duterte administration, the exponential rise of Chinese workers locally has only fueled Filipinos’ adverse attitudes toward the Chinese, a direct consequence of China’s aggressiveness in the West Philippine Sea.

This, in turn, has turned Duterte’s pivot to China a tough sell to the Filipino, exacerbated by anecdotal reports of Chinese misbehavior on tourist destinations, mainlanders taking jobs away from Filipino, and even tax evasion committed by some POGO firms ran after by the finance department.

Apart from Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, Koreans and Lebanese top the list of foreign workers in the Philippines. Aside from POGOs, foreigners were also mainly employed in manufacturing, information and communication, wholesale and retail, construction and finance.

In some industries, Leonardo Lanzona, labor economist at Ateneo de Manila University, said displaced overseas Filipino workers who have adopted skills abroad may help bring back some jobs from foreigners to Filipinos. But not in POGOs.

“I’m not sure if the companies, the POGOs themselves, would be willing to invest in training the Filipino workers, unless the Filipino would make their own investment,” he said in a phone interview.

“It’s easier for the company to just hire Chinese, especially if they’re looking for language. So in effect, they could save on training and other types of cost,” he said.

- Latest

- Trending