The workhorse of equity investing – mutual fund – is probably past its prime. There are forces at work that may relegate the actively managed mutual fund to being largely a retail investor’s instrument, next to the trusted insurance-cum-investment policy. Savvier investors are likely to move on.

Passive is in – the Indexing Revolution

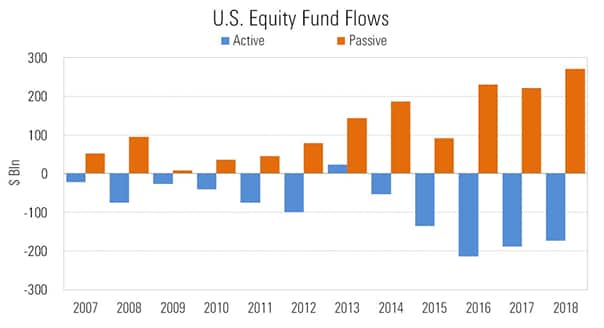

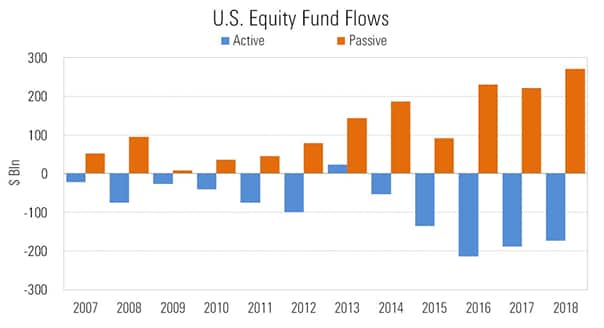

September 2019 was a turning point in the history of money management. The AUM (assets under management) of passively managed funds in the US crossed that of the active schemes for the first time. Looking at the AUM alone may mislead one into thinking that these two modes of investing are now equals. Far from it! The flows into actively managed funds over the last 10 years have been negative in all but one year. The opposite is true for passively managed funds – they saw inflows in each of the last 10 years. What is driving this steady march of passive funds?

Source: Morningstar Direct

Source: Morningstar Direct

Financial Economics – the theory underlying investment management amongst other things – has been evolving over last five decades. Two theories that won Nobel prizes – Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and the Fama-French Multi-Factor Model – led to two interesting paradigm shifts in investment management. CAPM was accompanied by the so-called Efficient Market Hypothesis. This is the idea that you can’t beat the market in the long term and consistently. The basis of this thinking was that any performance that deviates from the index is a zero-sum game – for every outperformer, there has to be an underperformer somewhere else, by definition. Taken in the aggregate, this means that the collective of equity investors can never outperform the market.

A subset, i.e., mutual funds initially claimed to be smarter than the average retail investor and thus expected to be on the better side of this zero-sum game. However, detailed research proved otherwise. The average equity mutual fund at best performs at par with the market – before costs. Take out the fees and costs and the average fund always underperforms. The claims of some mutual fund managers that they were smarter than their peers were also proven false. The winners of a given year didn’t remain so in the next and the losers often enough came to be winners in the subsequent year. You just couldn’t pick a consistent winner amongst mutual funds!

All this held true largely for the more efficient developed markets. It led to the first of the two phenomena that the developed markets are witnessing today – indexing! John Bogle, with his deep faith in Efficient Market Hypothesis, set out to create Vanguard – an investment management company that would offer only index funds. It took a long while for investors to bite into the idea, but they finally did, at least in the developed markets. Index ETF providers became even more cost-efficient with time and AUM – there is an index ETF in the US that charges literally nothing as management fees; many others charge 0.03-0.1 percent a year.

The sister revolution in smart beta

The second phenomenon is factor investing. This is a sort of compromise between indexing and active management. When told about indexing, people asked – what about the stocks that are obviously superior to their peers in the same industry? Can’t we generate outperformance by investing in companies that are better-run? The Fama-French Model gave some comfort to this line of thinking. It suggested that there are some ‘factors’ (such as value, size, momentum) that can lead to performance that is better than the market. For innovative investment managers, this meant they could invest in ‘factors’ and get some performance above market. Thus was born the sister revolution of indexing – smart beta!

Smart beta is a theme or a rule, as against a generalized active management of a fund. One can be overweight in companies with, say, high Return on Equity (ROE), and underweight on companies with low ROE. This doesn’t need anything more than the initial set-up of how to arrive at the tilt in a portfolio and where to get the data for ROE calculation each quarter. No need for a star fund manager and an army of analysts! The result is lower fees – around 0.25- 0.5 percent a year. Investors are also better off since they can evaluate the idea of a specific theme (such as ROE, growth, value) instead of checking out all the bells and whistles of the story laid out by a fund manager of an actively managed fund.

Smart beta funds make up about one fourth of the total passive AUM in the US – growing at a rate similar to index funds.

The Indian Case

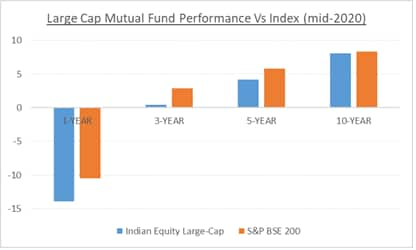

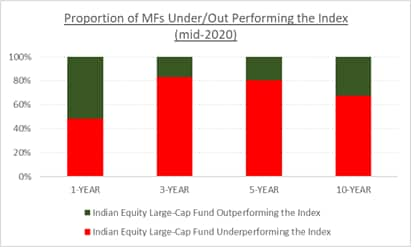

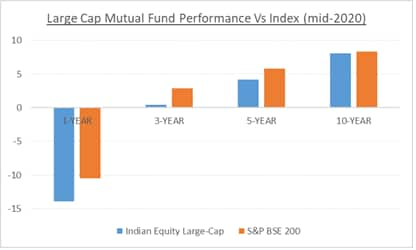

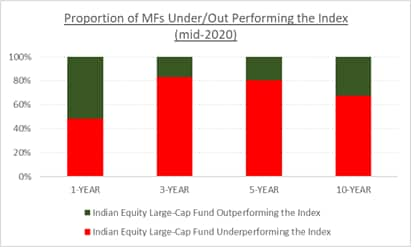

Our research in 2006 suggested that Indian mutual funds were not subjected to the same constraints as those in the developed market. There were consistent winners, and the average fund outperformed the market. Come 2020, however, and the things for Indian mutual funds started to look quite similar to those in the west. The performance of the average mutual fund is now worse than that of the index. The consistency of winners staying winners also came down. Graphs below show this as of mid-2020.

Source: SPIVA® India Scorecard

Source: SPIVA® India Scorecard

What changed? Indian mutual funds were tiny in comparison to the overall market back in 2006. For a small fund it is easy to outperform the market – all the more so in a market like Indian equities which was not quite efficient. By 2020, the Indian mutual fund industry grew to be of much bigger sizes – many individual equity fund schemes now have AUM of more than Rs 10,000 Cr. At these sizes, the efficient market hypothesis becomes all too real! The Indian markets have also become more efficient with higher liquidity and diverse set of participants. The opportunities to outperform have dwindled. The costs have started to eat into whatever small outperformance one could generate.

What next for India?

Three types of investment managers are likely to emerge in the future in India. The first type will be behemoths such as Vanguard and Blackrock in the Indian context – huge index ETF providers that charge next to nothing for indexing and small fees for smart beta.

The second type will be niche managers that have unique strategies of their own – which may or may not outperform the market, but would at least attract enough investors to buy into their story.

The third type will be investment advisors that focus on customization of equity portfolios for investors instead of obsessing about outperformance. This customization can be for emotional preferences such as environment or social impact. It can also be for smart beta themes that an investor prefers. This would be akin to creating a personalized mutual fund of your own – serving the proverbial ‘market of one’!

_2020091018165303jzv.jpg)