arvinder with his parents at his farm in Padlu village.

arvinder with his parents at his farm in Padlu village.Jarvinder Singh, 35

Padlu village, Kurukshetra, Haryana

Total Land: 13 acres; seven acres on lease

Crops: Paddy, chilli, potato, sunflower

On November 25, Jarvinder left his village to march towards Delhi along with other farmers as the group feared losing its land to big corporates because of the three new farm laws.

“Everyone in the village understands the threat. I believe that eventually because of the new laws we will lose our land to corporates such as Ambani-Adani,” he says.

The 13 acres of farming land that the family owns supports his parents, wife, 11-year-old son, his brother who has been largely bed-ridden following an accident last year, his sister-in-law and 20-year-old nephew. Since November 25, apart from Jarvinder’s brother, all male members of the family have been taking turns to join the protests at Delhi’s Singhu border. When Jarvinder returned on December 5 to tend to his crops, his son, nephew and 75-year-old father took his place at the protest.

Padlu, the family’s village, has a population of around 2,000. To supplement the income from their own land, the family has also been cultivating on an additional seven acres of land on lease, that has an annual rent of Rs 45,000 per acre. “I have one full-time helper. I hire daily wage labourers for Rs 200 per day during the harvest season. We may need about 50-60 workers per day when chillies are being harvested,” says the 35-year-old.

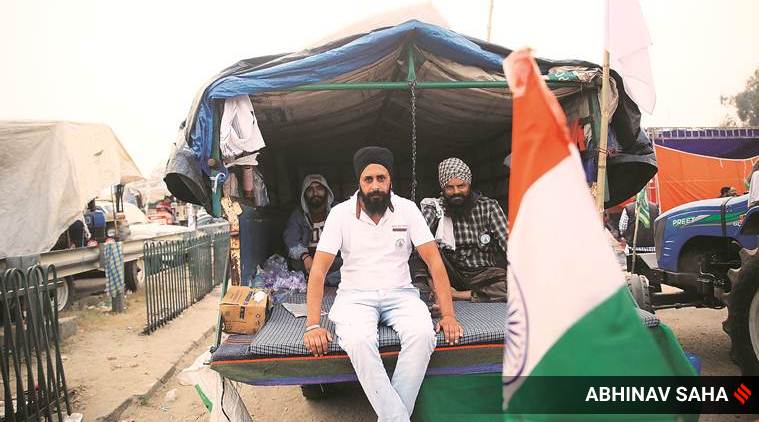

Jarvinder has been protesting at the Singhu border since November 25.

Jarvinder has been protesting at the Singhu border since November 25.

The family owns a tractor which they bought for Rs 8 lakh in 2014, a cultivator, a potato planter, a harrow machine, a rotavator, a land leveler, and a trolley.

Complaining about the poor sale of chillies this year, Jarvinder says, “I was expecting to sell them at around Rs 40 per kg, but instead it sold at Rs 10-12 per kg. I incurred a loss of more than Rs 10 lakh.” In comparison, during the same harvesting season, he made a profit of Rs 50-55,000 from his sunflower crop. And, from potato harvest in last December, he made a profit of Rs 10-11 lakh.

The family of eight lives in a single-storey home in their potato fields. Jarvinder began work on the farm after completing Class 10, but hopes for a “different path” for his son.

“I am sending him to a private school. It’s my dream to see him become an IPS officer. If that doesn’t work out, I hope he finds a job with a good salary at a private company. If that does not happen either, there’s always the Army. Farming is the last option,” he says.

‘If corporates come, they will treat us as employees’

Narpinder Singh, 40

Jatana village, Ludhiana

Total Land: Owns 13 acres

Crops: Grows paddy, including basmati, and wheat

Since November 26, Narpinder Singh and his tractor trolley have been on a different sort of a field — far from his 13 acres in Jatana village in Ludhiana, and parked next to a police barricade at the Singhu border.

Accompanied by villagers, Narpinder says he won’t go back till the farm laws are repealed.

“There is nothing for us in the new laws. The laws have given corporate houses direct entry into agriculture. Already, for crops with no MSP, we are at the mercy of private players. Once these new laws come in, that will happen in case of all crops. I am very worried and insecure about my future,” says Narpinder, who has leased out eight of his 13 acres.

This year, Narpinder sold his basmati at Rajpura mandi, 75 km away, for Rs 25,000 a quintal. He sold paddy at a mandi 2 km from his village for the MSP rate of Rs 1,888.

Narpinder Singh (Express photo by Rakhi Jagga)

Narpinder Singh (Express photo by Rakhi Jagga)

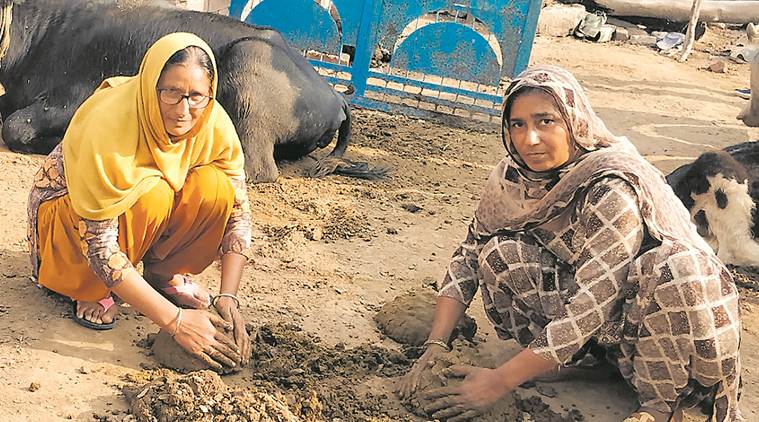

Over 300 km away, at Jatana, in Narpinder’s absence, neighbours and other villagers chip in with offers of help on the fields, with Narpinder’s mother Charanjit Kaur, 65, taking on the supervisory role.

For Narpinder, who dropped after his Class 12, farming is a key source of income. Narpinder’s wife Sharanjit Kaur, 39, is a teacher at a government school in the village. His father passed away few years ago.

Besides the house in the village, the family owns a tractor, a Swift car, and a Happy Seeder ground leveller. Thanks to the electricity subsidy for the agricultural sector in Punjab, they pay no power bills.

Besides work on the fields, Charanjit has to take care of two cows, three buffaloes and three calves. The family sells around 35 litres of milk a day to the Verka cooperative society. “We get Rs 22 a litre for cow milk and Rs 40 a litre for buffalo milk,” says Charanjit.

“I am a heart patient. So my granddaughters and my sister-in-law Daljit help me take care of the cattle,” she says.

“I can’t do much manual work but I go there once a day. Narpinder had sown the wheat before going to Delhi and luckily, the first batch of water and urea goes in only after a month of sowing. So there’s still a week left,” says Charanjit.

In Narpinder’s absence, his mother Chandrika is supervising work at the farm. (Express photo by Rakhi Jagga)

In Narpinder’s absence, his mother Chandrika is supervising work at the farm. (Express photo by Rakhi Jagga)

“Everyone is taking care of each other’s crops. Over 20 people from our village have gone to Delhi and they keep taking turns, but Narpinder has not come back even once,” says Charanjit.

She isn’t complaining, though. “What matters is that farmers are at the Delhi border, fighting…,” she says.

At Singhu, Narpinder says the dismantling of the system of arhatiyas won’t help. “We have an understanding with them. If corporates come, they will treat us as employees,” he says.

‘Hardly made money. Sold bottle gourd for Rs 2 per kg’

Gurtej Singh, 25

Nanheri village, Patiala

Total Land: 10 acres, of which he has leased out 5

Crops: Grows wheat, paddy and garlic on remaining 5 acres

Gurtej Singh first went to Singhu border on November 28. Since then, he has made one other trip, and is now home on a “brief visit”.

A postgraduate in political science, Gurtej worked in a private bank for a year in 2017, before taking to his family occupation of farming. His wife taught in a private school but has been without work since the lockdown.

Besides the house in the village, the family owns a tractor, plough and motorcycle.

Gurtej went to the Singhu border on November 28.

Gurtej went to the Singhu border on November 28.

Gurtej’s mother Paramjeet Kaur, 50, says that since the stand-off began, Gurtej and his three paternal uncles have been taking turns to go to Delhi, and to work in the fields. “We have many relatives in the village and we all take care of each other,” she says.

While Gurtej was away in Delhi, Paramjeet had to manage the garlic crop that they have sown on two acres and which will be ready for harvesting by April. The family has sown wheat on 2.5 acres, and green fodder and vegetables on the remaining land.

“The soil for the garlic crop has to be softened by digging. Since Gurtej was away, I got labourers to do it for Rs 35,000. I too worked with them. There’s hardly any money to be made. This season we grew bottle gourd but only got Rs 2 a kg. The same for maize — we had to sell at Rs 8 a kg. Who will grow other crops if this is the rate,” says Paramjeet.

In Gurtej’s absence, his mother, Paramjeet, has been managing the farm. (Express photo by Raakhi Jagga)

In Gurtej’s absence, his mother, Paramjeet, has been managing the farm. (Express photo by Raakhi Jagga)

Gurtej takes his wheat and paddy to Rajpura mandi, 20 km away, as the nearby Mardanpur mandi (less than 2 km) is always crowded.

“This has not been a profitable year so far, with an average decrease of about 10-15% on returns from paddy. I am running debts of over Rs 5 lakh,” says Gurtej.

‘Private players don’t offer good price for maize, moong’

Surjeet Singh, 47

Ransih Khurd village, Moga, Punjab

Total land: 15 acres

Crops: Grows wheat, maize and moong

A member of the Bharat Kisan Union (Ugrahan), Surjeet has been protesting at Delhi’s Tikri border since November 28. A few days before leaving, he completed sowing wheat on 10 acres of his land. On the remaining five acres of his land, he had sown green moong and maize, “but I did not get good rates for either of the crops,” he says.

On December 9, Surjeet returned to the village briefly to spray urea in his fields, and in the fields of some of his friends too. A father of two who has studied only till Class 12, Surjeet says farming is all he knows.

“I joined the protests because I know that the new laws will reduce my income further. Even now when I approach private companies with my maize and moong crop, they don’t offer a good price. Only the cultivation of wheat and paddy has kept us afloat,” says Surjeet.

At Ransih Khurd village, Pradeep’s wife Karamjeet Kaur (43) has been looking after the family’s cattle in his absence. “We use some of the milk at home and give the rest to the village’s milk society,” she says.

Reiterating the demands of the farmers of the village, she says, “We want the black laws to be scrapped, nothing else.”

Karamjeet says her daughter is interested in farming. (Express photo by Raakhi Jagga)

Karamjeet says her daughter is interested in farming. (Express photo by Raakhi Jagga)

Surjeet says he does most of the work on his field, and hires a few labourers to transport paddy. “I can’t afford anything more. Every year, my input costs increase and I now have a debt of Rs 6 lakh,” he says.

His children, a 15-year-old daughter and a 11-year-old son both study in English-medium schools nearby. Karamjeet says her daughter helps her with dairy work and has also developed an interest in farming.

“We want things to get better for our children. Earlier, I too sat on a dharna at a petrol pump in Moga, but now there’s a bigger morcha in Delhi. Only that will force this deaf government to listen to our demands,” she says.