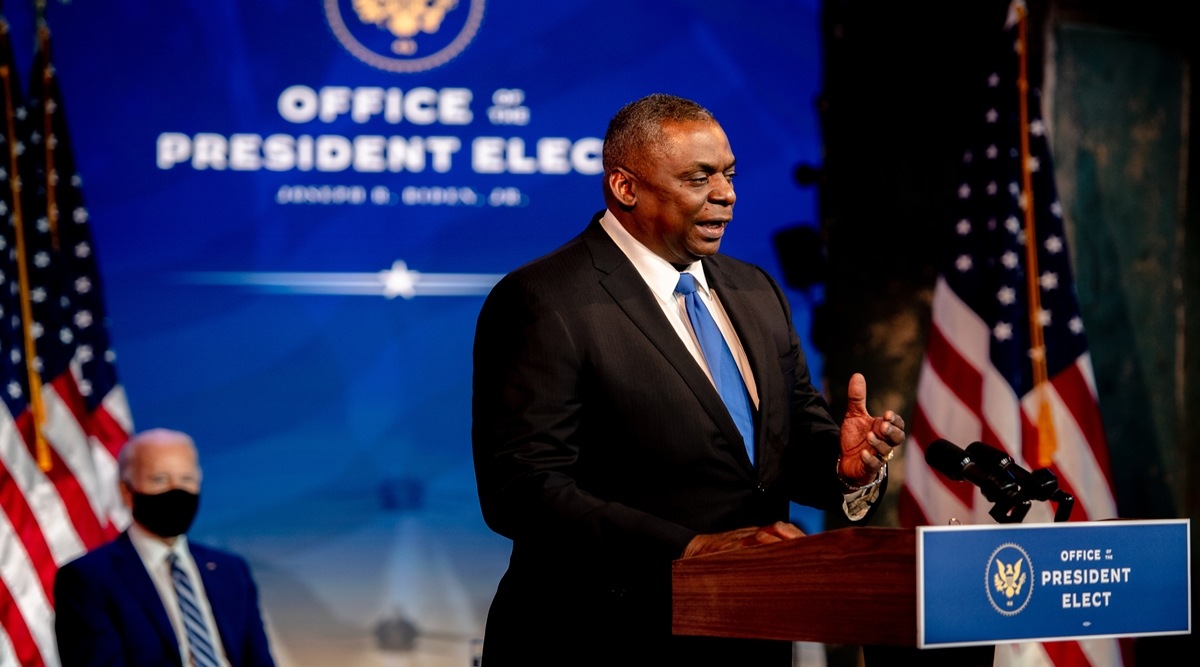

Retired Army Gen. Lloyd Austin, speaks at an event where President-elect Joe Biden announced Austin as his nominee to be secretary of defense, in Wilmington, Del., on Wednesday, Dec. 9, 2020. (Hilary Swift/The New York Times)

Retired Army Gen. Lloyd Austin, speaks at an event where President-elect Joe Biden announced Austin as his nominee to be secretary of defense, in Wilmington, Del., on Wednesday, Dec. 9, 2020. (Hilary Swift/The New York Times)Retired Gen. Lloyd Austin, who is on the brink of becoming the first Black man to be secretary of defense, rose to the heights of a U.S. military whose largely white leadership has not reflected the diversity of its rank and file.

For much of his career, Austin was accustomed to white men at the top. But a crucial turning point — and a key to his success — came a decade ago, when Austin and a small group of African American men populated the military’s most senior ranks.

As a tall and imposing lieutenant general with a habit of referring to himself in the third person, Austin was the director of the Joint Staff, one of the most powerful behind-the-scenes positions in the military. His No. 2 was also a Black man, Bruce Grooms, a Navy submariner and rear admiral. Larry Spencer was a lieutenant general who was the arbiter of which war-fighting commands around the world got the best resources. Dennis Via was a three-star general who ran the communications security protocols across the military.

And Darren McDew, a major general and aviator with 3,000 flight hours, was a vice director overseeing the plans the Joint Staff churns out.

At one point in 2010, the men thought they should capture the moment for posterity since nothing like that had happened before and likely would not happen again. They summoned the man who had made it happen, their boss, Adm. Mike Mullen, President Barack Obama’s chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, into a room for a photo.

“What is this about?” Mullen asked when he walked in.

“History,” McDew replied.

Now Austin is poised to make history again. His ascension to the top Pentagon job would be a remarkable punctuation to a career whose breadth showcases the scope of what the military can do on diversity when senior leaders act. But the singularity of Austin and his Black colleagues’ moment in power also demonstrates the entrenched system that has defaulted to white men at the top when 43% of the 1.3 million men and women on active duty in the United States are people of color.

The photo of Mullen with his senior Black directors and vice directors stands in contrast with another photo, taken a year ago, of President Donald Trump surrounded by a sea of white faces — his senior Defense Department civilian and military leaders. Today’s Joint Staff directors and vice directors are similar: All but one of those jobs are filled by white men. The exception is Vice Adm. Lisa Franchetti, a white woman, who is the director for strategy, plans and policy — a reflection of the inroads that the current chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, has made by appointing women to jobs they have never had before.

But as the country has focused on racial disparities and protests after the police killing this year of George Floyd, Defense Department officials have acknowledged that they have failed to promote Black men, who were fully integrated to serve in the military after World War II. They have offered a host of reasons, from a lower number of Black men in the combat jobs that lead to the top ranks to a tendency by corporate America to raid the best talent, to explain why so few senior leaders are people of color.

In a series of interviews over the past two months, Austin, Mullen and the Black men who ran the Joint Staff 10 years ago — most of whom went on to even higher levels of command — said the reasons given by the Defense Department’s top ranks are excuses.

“It’s a simple issue of leadership,” Mullen said in a recent interview. “If you want to get it done, you can get it done.”

At first glance, Mullen might be an unexpected choice to be the senior officer who would work to break racial barriers at the Pentagon. The son of a Hollywood press agent, he grew up in 1950s Los Angeles, where his high school senior class of 130 had only one Black student.

But the world opened up for him when he got to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1964: One thing the U.S. military does is throw together young men and women of all different races, at least at first.

Mullen was classmates with Charles Bolden, who would go on to become the first African American to lead NASA. The two teenagers had gotten to the Naval Academy via vastly different paths: Mullen through a basketball scholarship, and Bolden only when he wrote a personal letter to President Lyndon Johnson after being turned down for the Annapolis appointment by South Carolina’s congressional delegation, which included a segregationist, Sen. Strom Thurmond.

Mullen’s racial antennae went up slowly as he progressed through the ranks of the Navy. He could not help but notice that the higher up he went, the whiter the Navy got, until soon there were no people of color around him. “I would look up occasionally, and it was an all-white world,” he said.

By the time President George W. Bush appointed him first to lead the Navy in 2005 and then in 2007 to be chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Mullen feared that the Navy and the military as a whole were not keeping up with the country for which they fought. “I felt that the more unrepresentative we were as an institution, the farther we would drift from the American people and the more irrelevant we would become,” he said.

Enter Austin.

Austin, a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, was raised in Thomasville, Georgia, the same town that produced Henry Flipper, who was born a slave and in 1877 became the first African American graduate of West Point and the first Black noncommissioned officer to lead Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry.

Austin had helped lead the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division’s during the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, commanded a light infantry division in Afghanistan after that, and was back in Iraq as a ground commander in 2008 when Mullen arrived for a tour. Bush’s surge had started to quell the worst of the sectarian violence that had plagued the country, but U.S. troops were still dying, and the country was on the verge of a humanitarian crisis.

It was well known among U.S. command staff members in Baghdad that Austin loathed talking to the news media or doing on-demand performances for visiting dignitaries. But over dinner with Mullen at one of Saddam Hussein’s old palaces, he opened a map of Iraq and walked the Joint Chiefs chairman over what the U.S. military was doing on every piece of contested ground in the country.

“I was just blown away,” Mullen recalled. “I hadn’t run into anybody who had the comprehensive understanding of the ground war that he had.”

Austin said in an interview that during the dinner he was just focusing “on the X’s and O’s,” but remembers Mullen telling him “it was the best picture of the fight that he had gotten in some time.” Back in Washington, Mullen called Gen. George Casey, the Army chief of staff who was responsible for compiling names for promotions to Joint Staff’s top jobs.

“Is Austin on your list?” Mullen asked him.

“He said no,” Mullen recalled. “I said, ‘Put him on it.’”

By 2009, Austin was at the Pentagon as director of the Joint Staff, the first Black man to hold the job. Mullen also appointed another Black officer, Grooms, a baby-face Navy submariner whom the admiral had been mentoring for years with public strolls around the Pentagon to make sure other people took note, to be Austin’s vice director. Upon his arrival, Mullen told Austin to make the rest of Joint Staff directors and vice directors more diverse, too.

But when Austin went to the Army, Air Force, Marines and Navy asking for recommendations for high-quality candidates, he ran into a brick wall. Every list he got from the services, he said, was filled solely with white men. He returned to his boss a few weeks later saying he could not find any minority candidates.

The reaction, Austin recalled, “was one of the worst butt-chewings I ever got from Mullen. He said: ‘They’re out there. Go back and find them.’”

Austin went back to the services and told them not to bring him any more lists of only white men. He had learned a lesson: In the U.S. military, if he did not specifically ask that minority candidates be included on the lists for various posts, he would not get any.

“We did a second look and cast a wider net,” Austin recalled, “and found there were folks out there who were supremely qualified.”

The result was Via, who would rise to become the commander of the U.S. Army Matériel Command; Spencer, who would become the vice chief of staff of the Air Force; McDew, who eventually became the commander of the U.S. Transportation Command; and Brig. Gen. Michael Harrison, who became the commander of U.S. Army forces in Japan.

With the exception of Harrison, who retired after he was disciplined as a major general for mishandling a sexual assault case in Japan, all the men rose to become four-star generals and admirals.

On September 1, 2010, at a ceremony at Al-Faw Palace in Baghdad attended by Vice President Joe Biden, Austin became commanding general of U.S. and coalition forces in Iraq. It was the start of what has become a crucial relationship with Biden, now the president-elect.

Biden was already predisposed to like the general; his son Beau sat next to Austin, who is Catholic, during Mass in Iraq when Beau Biden was serving there. Austin and the elder Biden would go on to spend hours together in White House Situation Room meetings discussing Iraq and the Obama administration’s withdrawal of 150,000 troops from the region, developing a level of comfort with each other.

Biden, in an op-ed in The Atlantic on Tuesday, called the Iraq withdrawal, which Austin led, “the largest logistical operation undertaken by the Army in six decades” and compared it to what would be required to help distribute coronavirus vaccines throughout the United States, a job the next defense secretary will find in his portfolio. “I know this man,” Biden said Wednesday, formally introducing his nominee for defense secretary.

When Austin was appointed by President Barack Obama to be head of the U.S. Central Command — the country’s premier military command, and the one that fights the nation’s wars in the Middle East — he had risen higher in the military than any other Black man except Colin Powell, who had been chairman of the Joint Chiefs. Now Austin is poised to rise even higher as the next secretary of defense.

The Joint Staff director job that Mullen gave Austin set him up for all that came after. “You’re involved in the planning of sophisticated issues, interacting with the secretary of defense routinely,” Austin said. “People who might not have known Lloyd Austin began to know him.”

But even if confirmed by the Senate as the Pentagon chief, Austin may find himself running into the usual hurdles promoting people of color. One of Austin’s Black contemporaries on the Joint Staff, Spencer, recalled in an interview what happened when he once tried to fill an executive assistant job — a promising one that would ensure upward mobility.

“They kept sending me lists of all white candidates,” Spencer recalled. When he asked for a more diverse roster, he said, “the officer tells me, ‘Well, sir, it would look bad if you picked a Black EA because you’re Black.’”

Whether views like that handcuff Austin if he becomes defense secretary is an open question. During an interview before Biden asked him to take the top Pentagon job, Austin was adamant that senior leaders have to take responsibility for diversifying the senior ranks.

“People tend to choose the people to be around them that they’re comfortable with, and unless the leadership values diversity, this just doesn’t happen on its own,” Austin said. “It kind of makes you believe that having goals and objectives is a nice thing, but having requirements might be better.”