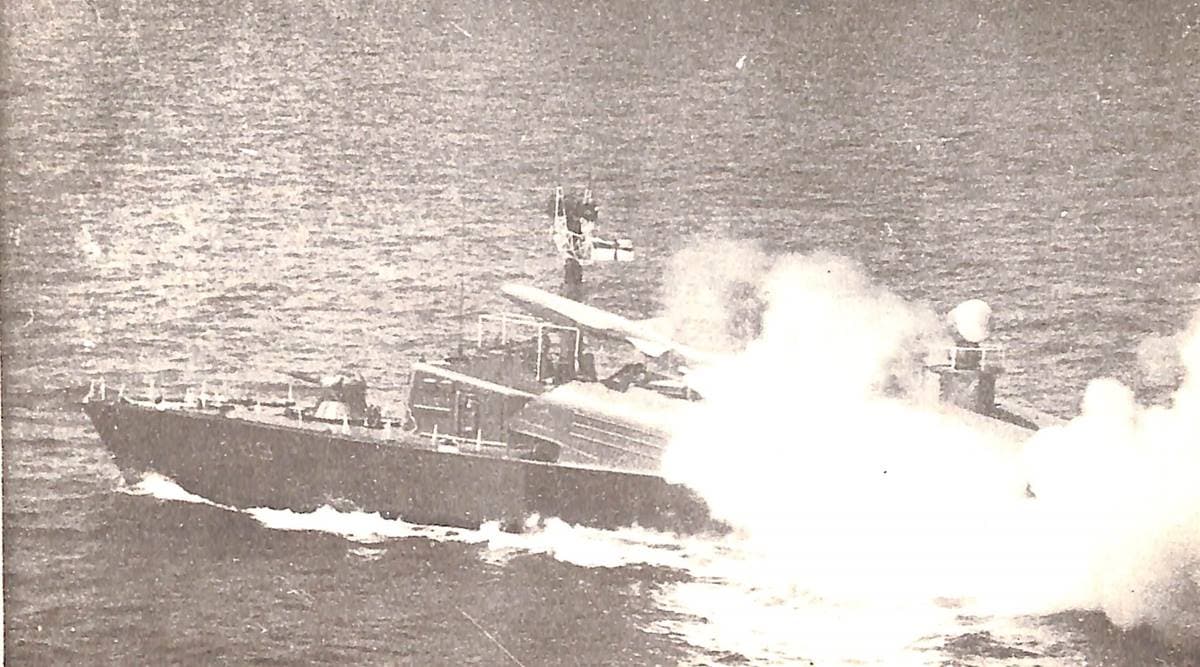

One of the missile boats which participated in the historic Op Trident, during a missile firing.

One of the missile boats which participated in the historic Op Trident, during a missile firing. Written by Lieutenant Commander Ankush Banerjee

The most profound truth of war is that the issue of battle is usually decided in the minds of the opposing commanders.

– BH Liddle-Hart

Through the Looking Glass — slightly obliquely

Our preoccupations are dominated by a conflict’s operational vis-à-vis tactical details whenever we reminisce, talk or write about a conflict – which ship fired how many missiles, how many soldiers fought, and died, which aircraft participated in an engagement, and so on. Numbers are an excellent aid to assess and take stock of scenarios. They are even better at adjudicating winner and loser and subsequently heighten the victor’s sense of triumph or the loser’s sense of despair. However, numbers and stock details only vaguely indicate the essence of the complexity, vulnerability, and intricacy at play behind most higher-order strategic decisions, the outcome of which we either deliriously celebrate or timelessly mourn. From a historical point of view, a qualitative exploration of the thought dynamics behind higher-order strategic decisions is just as critical as gleaning key ‘facts’ about the outcome of those decisions.

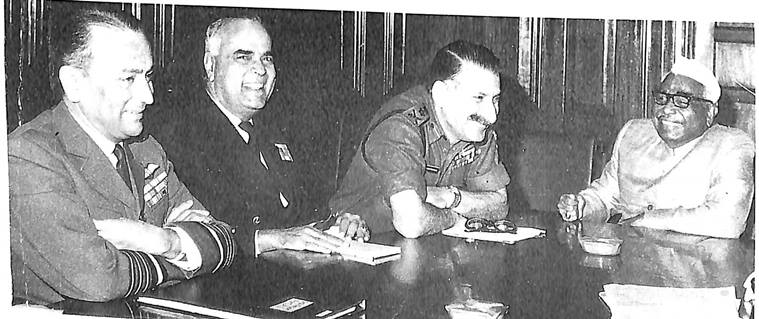

VAdm N Krishnan and Lt Gen JS Aurora call on President of newly formed Bangladesh Mujibur Rehman.

VAdm N Krishnan and Lt Gen JS Aurora call on President of newly formed Bangladesh Mujibur Rehman.

Whatever may be the end-result, sound military leadership has always been characterised by an unlimited moral liability to decide and to act, whenever called upon to do so. However, the soundness of such decisions has impinged, to varying degrees, on the interplay of underlying institutional dynamics and a leader’s personality.This article highlights and explores the complexity inherent in a few of the most challenging decisions faced by senior Indian Naval leaders during the war of 1971. It further describes, examines, and locates the importance of three essential leadership qualities which help in sound decision-making, namely, ‘tolerance to ambiguity’, ‘courage of conviction,’ and ‘the ability to take calculated risks’.

Slow and steady wins (more than) the race

The 1971 War was a watershed in the life of the young, 24-year-old Indian Navy. In both the previous conflicts of 1962 and 1965, the Navy’s role was limited due to their continental focus. Admiral SM Nanda, the Chief of the Naval Staff in 1971, was however, determined to change this situation.

It must be recognised that the Indian Navy of 1971 was very different from its previous avatars. From 1965 to 1971, much thought had gone into how to best capitalise and strategise India’s maritime position, given the available resources and existing threat perceptions. Over these ‘silent’ years, infrastructure was committed, new platforms acquired, and practical knowledge management frameworks were institutionalised. For instance, between 1969 and 1970, the following new acquisitions were made: five Petya class anti-submarine vessels (Kamorta, Kadmatt, Kiltan, Kavaratti and Katchall), four submarines (Kalveri, Khanderi, Karanj, and Kursura), submarine rescue vessel Nistar, two Polish built landing ships Gharial and Guldar, and five patrol boats Panvel, Pulicat, Panaji, Pamban and Puri. Further, in 1970-71, eight Soviet missile vessels (Nashak, Nipat, Nirbhik, Vinash, Veer, Vijeta, and Vidyut) were in various acceptance and delivery stages. Since these vessels were restricted in their endurance and could not have sailed across oceans, they were loaded on heavy lift merchant ships in the Black Sea and unloaded at Calcutta (now Kolkata) being the only port in India having 200-ton cranes that could unload these vessels. To conserve their engine hours, these vessels were then towed to Bombay(nowMumbai), where they were to be based, and where their surface-to-surface missile preparation facility called the Technical Position (later named INS Tunir) was set up. A large contingent of officers and sailors was also deputed to the Soviet naval base, Vladivostok, to undergo training in operating these platforms.

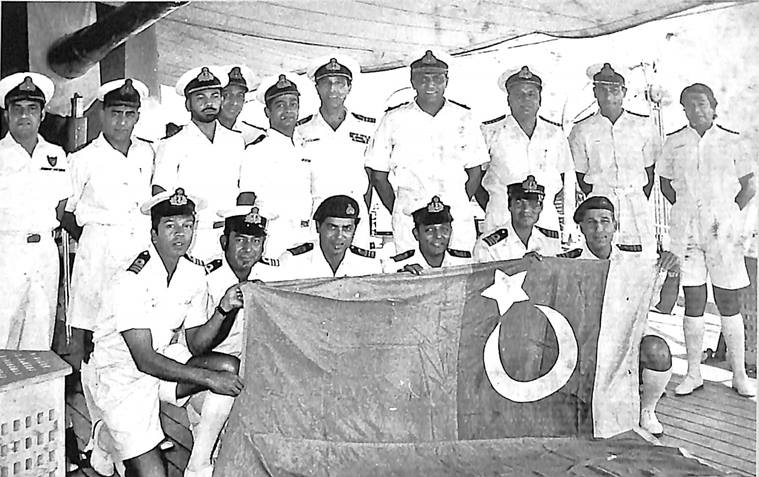

The Flag Officer Commanding Western Fleet with Commanding Officers of Fleet Ships (standing).

The Flag Officer Commanding Western Fleet with Commanding Officers of Fleet Ships (standing).

Such a humongous, long-drawn task of acquiring new units and technology, training human resources, and capitalising on them to gain optimum strategic advantage required meticulous planning at the highest echelons. It is reasonable to surmise that the seeds of Operation Trident and Python’s (daring attacks by these missile vessels on Karachi during the 1971 war) were sown while towing these missile vessels from Calcutta to Bombay. Likewise, the induction of INS Panvel before 1971 paid massive dividends when she played a stellar role during the daring naval commando operations at Mongla-Khulna from December 8 – 11.

Thus, if 1971 saw the Indian Navy operate from a position of strength than in the previous years, it was because of focussed preparation, an excellent strategic mindset, and the ability to anticipate adversity.

Mountaintops inspire leaders…

Most importantly, resolute, determined leadership at the helm supported by a similarly aligned and equally aggressive support system in the form of officers such as Vice Admiral N Krishnan as the Flag Officer Commanding in Chief, Eastern Naval Command (FOCINC East), and Captain Swaraj Prakash, Commanding Officer of INS Vikrant, made all the difference.

Admiral SM Nanda, the Chief of the Naval Staff at that time, was resolute that the Indian Navy must adopt an aggressive posture. This resolve came from awareness of the decisive, force-multiplying effect that such maritime posturing would have on the war’s outcome. One should also remember that this was the first time the nation was being urged to look beyond its continental focus. Such aggressive maritime posturing translated into taking pre-emptive operational offensive, attacking Karachi, enticing the Pakistani fleet to battle, and cutting the sea lines of communication between East and West Pakistan. Each of these strategies translated to effective on-ground tactics, which had a debilitating effect on the enemy’s morale. For instance, the Eastern Naval Command’s articulation of this strategy entailed attacking Chittagong, Chalna, Khulna, and Mongla from the seaward, destroying enemy shipping, and conducting diversionary or real amphibious operations.

The Chiefs of Staff of the 1971 Campaign with Defence Minister Jagjivan Ram. Air Chief Marshal PC Lal.

The Chiefs of Staff of the 1971 Campaign with Defence Minister Jagjivan Ram. Air Chief Marshal PC Lal.

… But valleys mature them

It would be interesting here to delve upon few of the leadership challenges faced by Admiral SM Nanda.

One of the first challenges he faced was to ‘normalise’ the idea that Karachi was penetrable from seaward, and that we could do it. To infuse this idea into the institutional thought paradigm, he devised numerous war games. He pushed his Commanders to think, critically assess and rationally analyse – ranges, payloads, depths, distances, costs – the world seen through the deadly play of numbers; their alignment eventually dictating winner and loser.

It is fascinating to note that Admiral Nanda did not speak through his rank — even though he was the CNS. Instead, he devised simulations and war games, which pushed and empowered his team to think of newer possibilities than those they knew existed; which made them tell themselves: Yes! this can happen, we can do it; yes! the Pakistani Navy obviously could not be everywhere; yes! they would be forced to defend their only harbour; yes! the citadel of Karachi can be stormed! and the rest, as they say, is history.

Wars, they say, are primarily fought and won in the mind. The Indian Navy had already won the first round from the enemy when Admiral Nanda won himself a dedicated, driven, motivated, and focused team, which placed its trust in his convictions.

Courage of conviction is one of the essential traits in Leadership literature. However, what leaders at all levels must understand is that this stellar quality becomes genuinely effective when one nurtures the ability to empathise with the team’s limitations and has the practical knowledge to transmute these limitations into something awe-inspiring. Thus, the obvious prerequisites for ‘courage of conviction’ to work are empathy and sound, practical knowledge.

‘Can she at least steam?’, or the power of the first small step

Vice Admiral GM Hiranandani, in his book Transition to Triumph (2000), univocally describes Admiral SM Nanda’s style of leadership as that “whenever he was confronted with a vexing problem, he would go…and sit down with those he considered knowledgeable…listen carefully to all views…and gradually evolve workable solutions, making it clear that the responsibility for the final decision would be his.”

It would be intriguing to draw attention to another critical conundrum that had vexed naval policymakers in the early part of 1971. Vikrant, the only aircraft carrier of the Indian Navy at that time and the primary unit around which the Navy’s concept of operations was based, had a crack on one of its boilers. Her speed was restricted which implied she might not be able to fly aircraft from her deck and make her vulnerable to detection by the enemy.

Initially, when the problem was discovered, the first question asked by the leadership was, “what if we operate on three boilers?” (she had a total of four boilers). This would certainly preclude its air operations. The follow-up question from the leadership was, “Are we at least able to steam?” to which the answer was an optimistic affirmative. Thus, she was sailed out of Bombay to the East Coast. With more careful consideration across the echelons, it was decided to auxiliary steam with the remaining three boilers. Successive trials proved encouraging. By the end of June 1971, it was clear that the sea trials had been successful. Vikrant was ready for action!

I would argue that the apparent extrapolation of ‘conviction’ lent the ability to the naval leadership to take risks and accept accompanying uncertainty, without being despaired by the inherent unpredictability that comes with those risks. In practical terms, this translates to choosing to approach a little bit of the problem every day – steadily, patiently and resolutely – with the intuitive understanding of when to stop, when to push a little harder, and when to go in for the kill. This also translates to being patient while breaking down a big problem, bit by bit, and gauging how far one can push it. After that, go back to the drawing table, and continue this iterative process over and over until one has a gallantly steaming aircraft carrier, bombing the enemy’s coast. Credit is due to the Indian Naval leadership for addressing the issues with Vikrant in such a mature, patient, resilient manner.

As a footnote, Vikrant’s presence and contribution to naval operations on the Eastern front were a game-changer! She steamed with only three boilers instead of four. However, Seahawk fighter aircraft were launched and recovered on her deck, even as each boiler was strapped with steel bands to minimise damage in case of an explosion. In addition to the deadly air-strikes, Vikrant also blockaded the Eastern seaboard, completely choking the Pakistan Army which was occupying East Pakistan.

Epilogue

This is the raw, unbridled, awe-inspiring power of sound leadership. The irony that one man asking, “can she at least steam?” caused a Domino effect, which led to incessant bombing of the Pakistani Army in Chittagong by fighter aircraft of Vikrant, should not surprise us. Or Karachi, for that matter. However, that is a story for another day.

Lieutenant Commander Ankush Banerjee is a serving Naval Officer presently posted at Naval Headquarters, New Delhi and is keenly interested in Military Ethics and Leadership Studies.