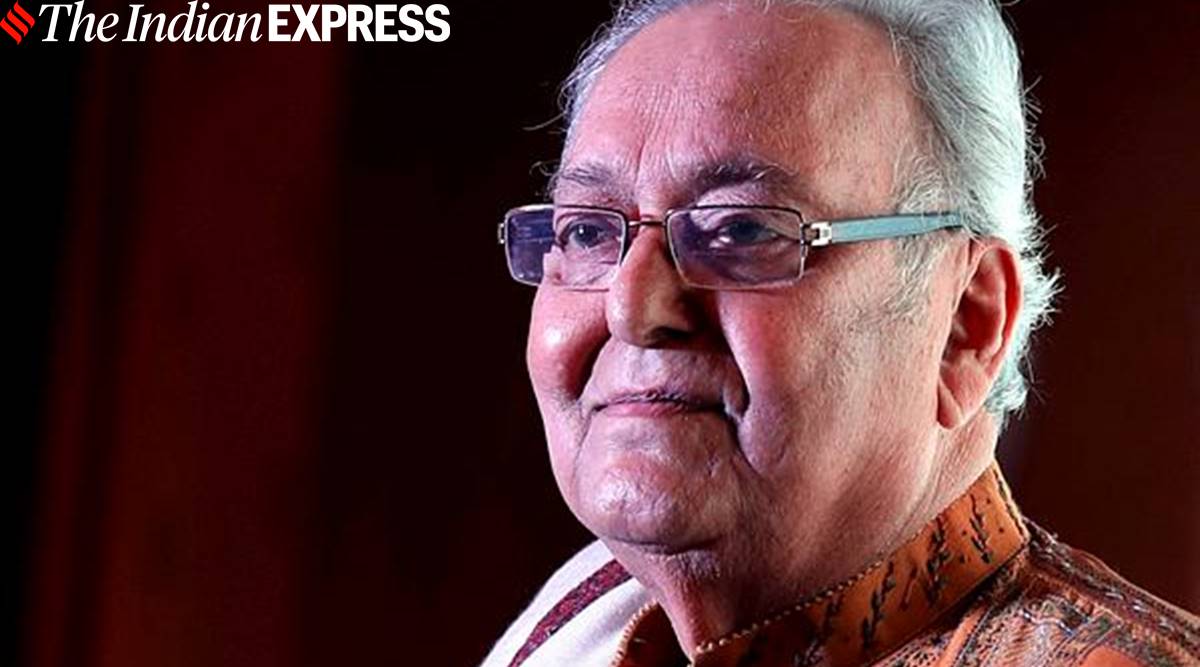

Soumitra Chatterjee was admitted to a hospital in Kolkata on October 6 after he tested positive for COVID-19.

Soumitra Chatterjee was admitted to a hospital in Kolkata on October 6 after he tested positive for COVID-19.There’s a Soumitra Chatterjee story that my septuagenarian father is fond of recounting. It is set in 1965, the year after Satyajit Ray’s Charulata released to critical acclaim. Having acted in films such as Abhijan (1962), Pratinidhi (1962) and Saat Paake Bandha (1963), Chatterjee, then 30, was already a star. Unlike many of his peers, including the matinee idol Uttam Kumar, he was still accessible. So, when a bunch of teenagers, my father among them, landed up at his Purna Das Road apartment to invite him to their high-school social, Chatterjee gave them a patient audience. He would be away at the time of the event, but Chatterjee said he’d be around if an occasion came up again. Some of his friends had dismissed it as bombast, but my father still remembers his surprise when the next year, he heard about Chatterjee participating in street protests in Calcutta against famines and food inflation during the second phase of the Khadyo Andolan (food movement) in Bengal. “Not just a fine actor,” my father likes to rest his case, “but a man of principles.”

In how many ways can one mourn Soumitra Chatterjee? His prodigious talent has been extolled by critics; his colleagues have spoken of his discipline and dedication. A Left ideologue, Ray’s protege wore his politics on his sleeves, showing up at protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act or to speak up for a director who found his film banished from theatres in West Bengal without an explanation last year. But to followers of Bengali cinema, he was that rare creature — an actor who bridged the gap between stardust and reality, and an intergenerational artiste.

In a state soon to witness massive political upheavals, including the Naxalite movement, my father’s generation entered adulthood with Chatterjee’s Apu (Apur Sansar, 1959) and Amal (Charulata, 1964; Pratinidhi, 1965), dreamer and revolutionary; brash Narsingh (Abhijan) and suave Ashim Chatterjee (Aranyer Dinratri, 1970). If his finest work was with Ray, Chatterjee was also equally malleable to the vision of mainstream filmmakers Ajoy Kar, Ashutosh Bandyopadhyay and Tapan Sinha, whose films focused on middle-class family life. And so, in a tumultuous decade, he came to symbolise both intellectual succour and Everyman — often browbeaten by life but indefatigable in his love for life. By the time the Eighties rolled in, Chatterjee came to us as Feluda and Khidda, urging his audience to use their magajastra (intelligence) and to “fight” in the same way that he had taught swimmer Koni in director Saroj Dey’s 1986 film (Koni).

The cultural accoutrements to a middle-class upbringing in Kolkata in the Eighties and Nineties included shruti natoks (audio plays), visits to the annual boi mela (book fair), to Nandan for films and the Academy of Fine Arts for plays and recitals. As much of a cliche as it is about Bengal’s cultural landscape, it was difficult, if not impossible, to avoid the troika of Rabindranath Tagore, Ray, and, over time, Chatterjee. Much before my generation saw him on screen, he was the voice in our heads when we learned Sukumar Ray’s Abol Tabol or read Jibananda Das as an adolescent. We trailed our parents to watch him on stage in productions such as Neelkantha, Ghatak Biday or Tiktiki; his rendition of Amit from Tagore’s Shesher Kabita gave us our first fuzzy idea of love before we watched him in movies and marvelled at his versatility.

If his life remained circumscribed by Bengal, Chatterjee’s oeuvre certainly was not. He remained a bridge between generations, the arc of his characters reflecting the work of time on our lives. He is forever Apu, Amal and Mayurbahan (Jhinder Bandi, 1961), true, but he was also Biswanath Majumdar (Bela Sheshe, 2015), a 75-year-old man who decides to divorce his wife after nearly five decades of marriage, or octogenarian Sushovan, a once formidable professor, whose slow descent into dementia in Atanu Ghosh’s Mayurakshi (2017) is one of the most emotionally-wrought cinematic experiences of recent years. In turning to his artistic journey, I stumble upon odd things — glimpses of familiar faces in the characters he played, memories of lost afternoons with my parents debating Chatterjee’s work, and, poetry, lots of poetry, that I didn’t realise I remembered till I heard it in Chatterjee’s baritone again.

Actor, orator, poet, thespian — there are many ways to remember Soumitra Chatterjee. But there is only one way to mourn him — with gratitude.

paromita.chakrabarti@expressindia.com