The company’s business is structured in such a way that its shares are meant to follow the price of uranium, which makes it a good way to get exposure.

The global uranium market has an annual deficit of around 30 million pounds and prices need to recover to at least $50 per pound to incentivize the opening of mines.

The Athabasca Basin is a terrible place for a uranium mine and the timeline for the recovery of uranium prices is impossible to predict.

With this in mind, I think investing in Uranium Participation provides a very good long-term exposure to the uranium market recovery thesis.

Objective:

• To provide investors with "pure" leverage to the uranium price without taking on mining or resource risk

• To let investors speculate on future changes in the uranium price by way of trading the shares of UPC

Introduction

There are two main companies which aim to provide direct exposure to uranium prices, namely Yellow Cake (YLLXF) and Uranium Participation Corp (OTCPK:URPTF).

UK-based Yellow Cake should be more attractive for European investors, while Canada-based Uranium Participation should be the vehicle of choice for North American investors.

I’ve already written on SA about Yellow Cake twice and in light of the interest in my article on Cameco (CCJ) from November 11 as well as my statement that prices need to return to at least $50 per pound of U3O8, I think it’s worth taking a look at Uranium Participation and the uranium market.

The last great uranium bull market

If you think platinum has been a frustrating commodity to invest in, you should look at the uranium price chart.

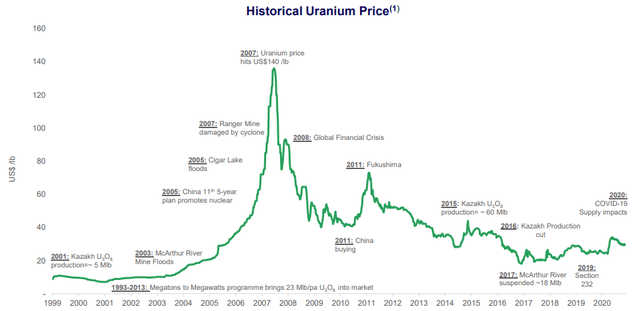

(Source: Yellow Cake)

Best-selling authors like Jim Rickards, uranium company CEOs, as well as investors have been talking about a new great bull market for years, but this has so far failed to materialize. I think it’s important to understand the reasons for the last one, by which I mean the parabolic price increase which started in 2004 and ended with a peak of $140 per pound in 2007.

As you can see from the graph above, the major catalysts were floods at Cameco’s main mines, a natural disaster at Ranger as well as the inclusion of nuclear energy in China’s five-year plans. This means there was disruption in supply as well as a perceived increase in demand, which is the perfect recipe for a price rally in the commodity markets. With the industry relying on long-term contracts, the flooding of Cameco’s mines ironically ended being the best thing that could have happened to the company.

There was no uranium shortage, but the idea of a tightening market took hold of the industry for a few years. I’ve seen the same happen with palladium, cobalt, lithium, and rare earths over the recent years. What this meant for uranium was that utilities scrambled to secure supply, which led to much higher prices.

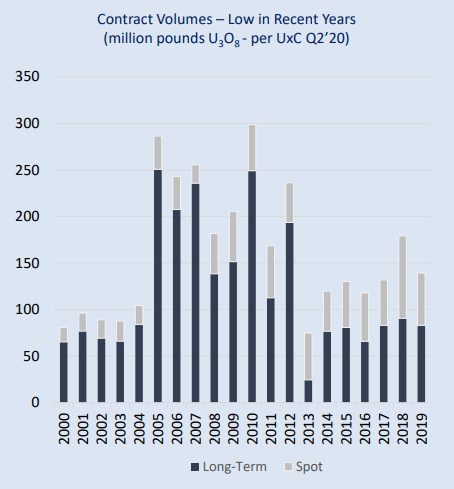

(Source: Uranium Participation Corp)

The current state of the uranium market

In 2019, the reactor requirements of utilities worldwide totaled 169 million pounds of U3O8 and average uranium price paid by US utilities was $36 per pound. Long-term contracts accounted for 85% of purchases. This makes uranium a mere $6 billion market, which is just half of the rhodium market for example. Yet, the market capitalization of Cameco and Kazatomprom alone is higher than the annual uranium sales value due to the widely-accepted idea that uranium is significantly undervalued.

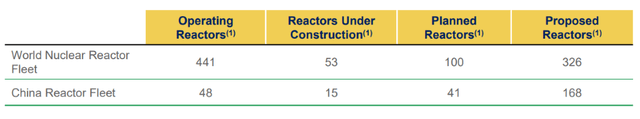

The first most widely mentioned reason for this undervaluation is that there are a lot of nuclear energy reactors being built, which will drive up uranium demand.

(Source: Yellow Cake)

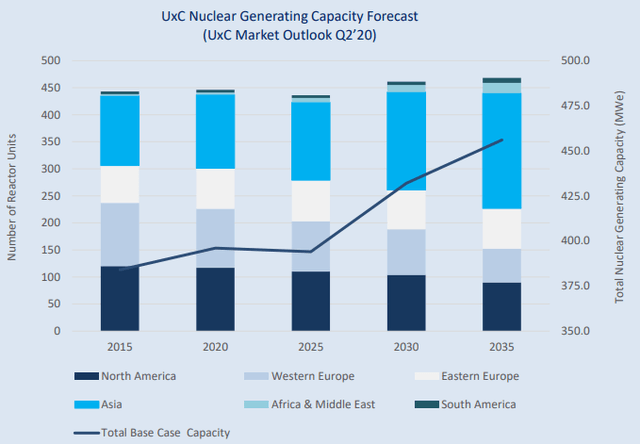

However, this doesn’t take into account the fact that the opening of new reactors will barely compensate for the closure of facilities in Europe and North America.At the moment, UxC predicts a growth in nuclear capacities until 2035 by barely 1% per year.

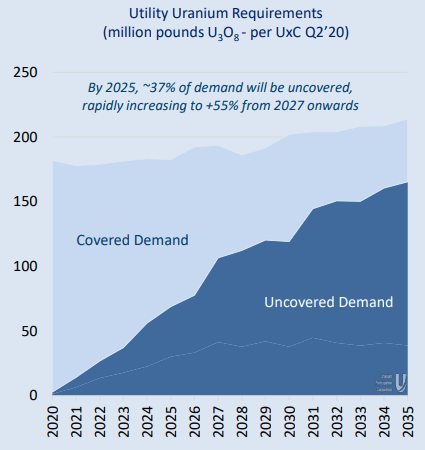

(Source: Uranium Participation Corp, with data from UxC)

The second widely mentioned reason is uncovered demand, with a total of 1.5 billion pounds needed until 2035. However, this is equal to an average of around 100 million pounds per year, which isn’t that far off from the annual volumes on the long-term market from the past several years.

(Source: Uranium Participation Corp, with data from UxC)

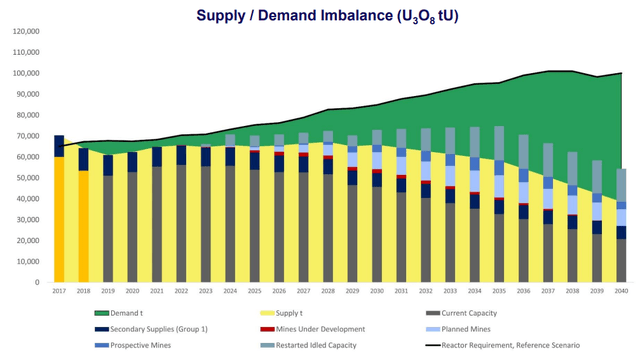

And the third widely mentioned reason is the structural deficit. At the moment, the world requires around 79,500 tons of uranium oxide per year, of which just over 80% comes from mines and the remainder from secondary sources such as civil stockpiles.

(Source: Yellow Cake)

The deficit is set to continue widening and the most important question is this - when is secondary supply going to deplete? According to UxC, global inventories stood at around 1.79 billion pounds U3O8 as of the start of 2018, with 53% held by utilities, 34% by governments and 13% by suppliers, traders and financials.

What to expect in the future

Usually, the pipeline needs around three years' worth of inventory, so we can remove around 500 million pounds. According to UxC, strategic inventories and trader inventories account for another 300 million pounds. There are another 600 million pounds held by the US and Russian governments and the remaining uranium is held by utilities as commercial inventories. However, up to 10% of the commercial inventories of utilities can be considered mobile, which effectively means that the uranium market is currently at the mercy of the governments of the USA and Russia.

With secondary supply covering around 30 million pounds per year at the moment, the USA and Russia can theoretically suppress uranium prices for well over a decade.

The reason that in my article on Cameco I said that prices need to return to at least $50 per pound of U3O8, is that's the level required to stop the shutdown of current mines and incentivize the opening of new ones. At the moment, full costs for around 40% of uranium production are above spot prices.

(Source: Kazatomprom)

Investor takeaway

My thesis is that uranium prices need to recover to at least $50 per pound, but it’s unclear when that will happen. If this is a decade away, investing in uranium companies would be a bad idea because most of them are burning through cash reserves and share dilution is common in the sector. However, an investment in Uranium Participation would still provide a return of around 60%, which isn’t that bad for a ten-year period.

Of course, owning shares in companies provides a higher leverage to uranium prices and would be a much better strategy if the latter soar in the near term. However, I think this is unlikely to happen because the events that led to the last great bull market can’t be repeated. China’s ambitions are already clear and the technically-challenging Athabasca Basin in Canada is barely producing any uranium at the moment.

Speaking of Athabasca, the latter is full of basement-hosted deposits, which are an engineering nightmare, as explained by Baselode Energy (OTCPK:BSENF) CEO James Sykes, who discovered the Arrow deposit.

With this in mind, I plan to avoid investing in the likes of Cameco, Fission Uranium Corp (OTCQX:FCUUF), NexGen (NXE), Denison (DNN), and IsoEnergy (OTCQX:ISENF).

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: I am not a financial adviser. All articles are my opinion - they are not suggestions to buy or sell any securities. Perform your own due diligence and consult a financial professional before trading.

Editor's Note: This article covers one or more microcap stocks. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.