Twenty-five years later, DDLJ more than survives a rewatch, and draws us again into its circle of charm.

Twenty-five years later, DDLJ more than survives a rewatch, and draws us again into its circle of charm.My best friend and I first watched Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge in a rundown single-screen cinema. We were 15 and defiant, a little torn between MTV and antakshari, but quite certain that our destiny was to leave this sleepy town where films arrived six months late and to outgrow homes that were bewildered by our desires. The love story of Raj and Simran spoke to us, as it did to so many more who were a part of that mixed-up cultural moment, though it has been bitterly criticised since as a copout of a glorious Hindi film tradition of rebellious love. Twenty-five years later, it more than survives a rewatch, and draws us again into its circle of charm, with its memorable music and dialogues, and its insistence on the madness of love (pyaar hota hai deewana sanam). Is it a regressive film? DDLJ, of course, takes a sanskari turn for the worse in its final 45 minutes, but is that the only interesting question to ask of this iconic film? That might be a bit like condemning Jane Austen for the deep regard in her novels for property, reason and order, at the cost of missing her tartness and wit.

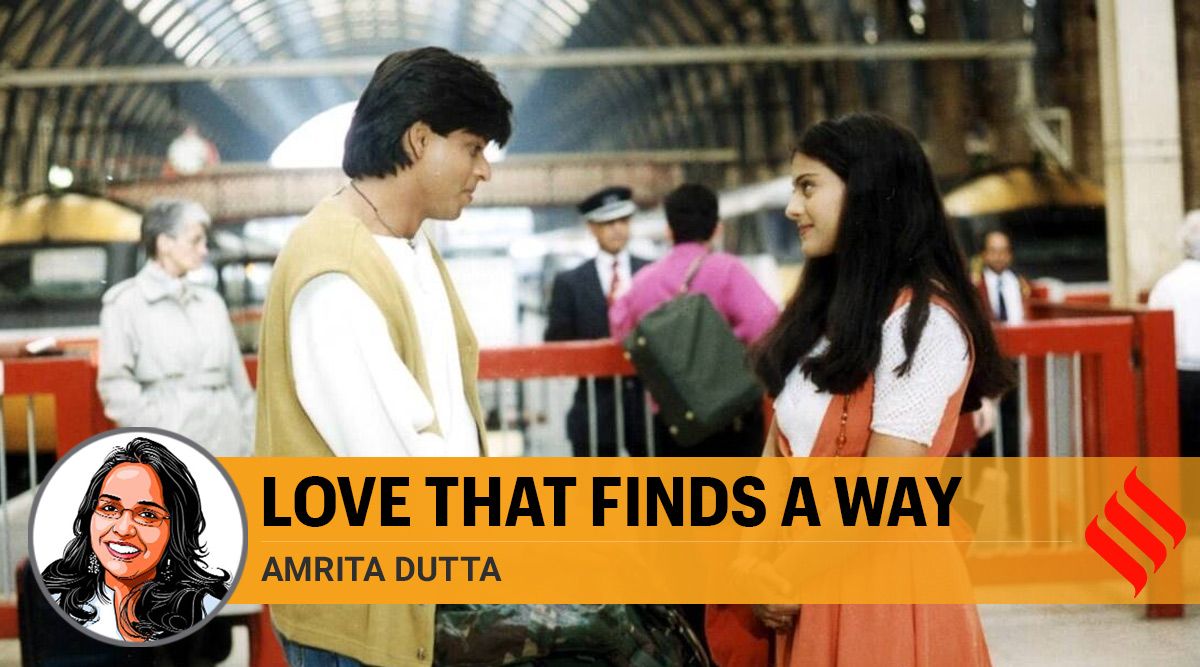

The corpses of star-crossed lovers are littered across Hindi cinema; only about seven years before Raj-Simran manage to catch that train, Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988) had ended in a bloody reinstatement of clan honour. But releasing four years after liberalisation of the economy fractures the Nehruvian consensus by injecting desire, money and speed into our bloodstream, DDLJ refuses to walk that path. It steps into a different world, where the young will not stand to be sacrificed, but are willing to strike a pragmatic deal —on their own terms. Even the actors look far from classic romantic protagonists. SRK’s Raj, who struggles throughout the film to keep his shirt tucked in; Kajol’s dark, unibrowed Simran, who can be bewitching one moment and ordinary as the girl-next-door, nose buried in a book, the next; who is both the sexy towel-wrapped gamine dreaming of love, and the dutiful daughter praying to god. Most touchingly, it’s her mother (Farida Jalal in a glowing role) whose kindness creates a safe space for both these selves.

The power of the film lies in the encounter it stages between these contradictions, between tradition and disruption, an idealised des and a Europe that can no longer be stereotyped as evil, and between romantic love and family — and tells us, with that irreverent Shah Rukh Khan chuckle, that it’s possible to have them both. It had its parallel in the country we were becoming, which needed both new money and old, entrepreneurial spark and social capital.

Much of the misreading comes from scanning stories for messages and morals to determine “whose side” a film is on, when cinema is far roomier, and will often resist such rigidities. The film slides into a politically incorrect plea to tradition but also repeatedly pits young desire against outdated custom. “Are you really going to marry a person you have never met?” is a question Simran is made to ponder, again and again. I would argue that DDLJ is also the education of patriarch Baldev Singh, who comes off as a misguided man who has shut himself and his family in an arid, niras caricature of Indian-ness — and not an unblemished authority figure. Like most love stories, DDLJ takes the side of pleasure. Baldev Singh’s high-minded suspicion of the Western lifestyle is undercut by the delight in Simran and Raj’s journey through gleaming Europe. There is an “official” stance against pre-marital sex being sinful for Indians, but quite a few transgressions play out in a song of intoxication — and a fake bedroom scene, the most intimate in the film, that imagines this illicit desire, before pulling back Raj and Simran into the folds of “Indian-ness”.

Perhaps, then, a film is not only the flag that it appears to wave, or the sermon it readily spouts, but also the longing that makes it turn (palat) to look at forbidden love. Years later, Sairat (2016) would ask devastating questions of the radical promise of eloping for love, given the emotional violence it wreaks on lovers — and of the possibility of love in a caste-wrecked society. Though DDLJ’s spirit is more accommodative, by spurning the so-called revolutionary trope of lovers running away, Raj pulls the film into interesting directions. The macho men go off to hunts. To win his dulhaniya, Raj makes friends with his sasural, and especially its women, by entering the kitchen, grating carrots, helping them pick saris — a kinder version of what the Indian bahu is ordained to do. This is SRK at his best, as writer Paromita Vohra has often argued, creating a fluid space of identities, allowing for mischief and transgression, and shaping a masculinity that is in dialogue with women, that is confident enough to drape a dupatta and break into dance. It does not stay the course, and the film degenerates into a 1980s film in the final minutes.

DDLJ was spot-on in its confidence in the power of post-liberalisation Indian love, which has, since then, bent many rules to make space for pleasure. For a privileged but not insignificant minority, that moment opened the doors to possibilities of living together and pre-marital sex, to marriages that cross communities and languages. Like many others, I have watched this quiet transformation in my own family, though marriage, itself, remains a patriarchal institution run on the emotional and sexual labour of women — and defended against incursions of caste and religion. That’s the conservatism that the film, like many of us, eventually commits to. But it offers a beguiling promise that a changing culture need not have a schizoid split at its heart. The discontents of liberalisation have exposed that promise, and that is, perhaps, where our disappointments with DDLJ too lie.

This article first appeared in the print edition on November 14, 2020 under the title ‘Love that finds a way’. Write to the author at amrita.dutta@expressindia.com.