Every fourth year, on the first Tuesday of November, the United States conducts its presidential election. The expectation is that after months of election frenzy and billions of campaign dollars spent, the US would finally have a president-elect by the end of that Tuesday. However, this time around, that Tuesday never seems to end and neither does the process of counting votes to find out the winner of the 2020 US election — Democratic Joe Biden or Republican and incumbent Donald Trump.

Instead, what we have are waves of ballot counting, electronic, paper and mail-in, staggered over days, and court cases causing collective national anxiety and ennui. But as CNN journalist Chris Cuomo said on Friday, inaccuracy would have caused greater anxiety. For Indians stoically used to multiple phases of polling — three in just the ongoing Bihar assembly election – the spectre of delay in the world’s oldest democracy seemed baffling.

As popular consensus is drummed up for ‘one nation, one poll’ under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, what is especially stark about the American election is the ‘disunited’ nature of election rules and counting procedures.

And for this reason, the US electoral counting is ThePrint’s Newsmaker of the Week.

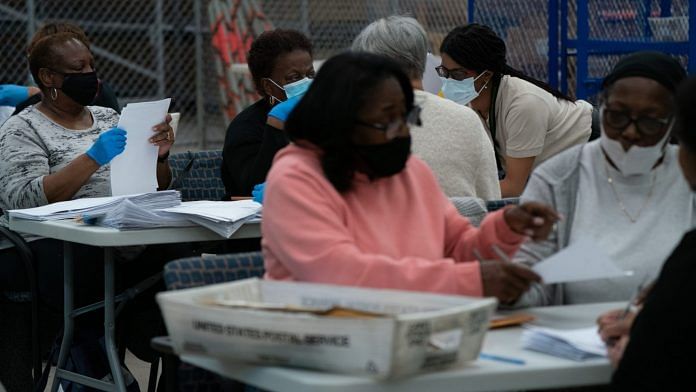

While the hard-working election officials and volunteers continue to get through the hundreds of thousands of ballots still left to be counted, President Trump, not too impressed with the direction of the results, has gone on a rhetorical rampage about “illegal votes”. On the night of the election on 3 November, he demanded counting of votes be stopped and declared his own victory. Never mind that five ‘swing’ states that would eventually decide the 2020 election were still counting their votes. Meanwhile, his campaign has already filed lawsuits in most of these five states, challenging the validity of the mail-in votes.

Back home in India, where people are only too keen to compare themselves with the world’s oldest democracy, an American sitcom-like chaos in the US has polarised an amused Twitterati. While some quip that the ‘leader of the free world’ may very well outsource its electoral process to the Election Commission of India, which is quietly and rather seamlessly conducting the election in Bihar, others are mesmerised by the transparency and the decentralised nature of the US electoral institutions.

Too much decentralisation

For all its flaws, the fervently independent American institutions – from the federal level to various counties – remain enviable for democracies around the world.

In the US, it is hardly unimaginable for an electoral official in some suburban county of Nevada or Georgia to talk down to the president, reminding them of constitutional values. It is only expected then that even as President Trump wrongly announced his victory mid-counting, and went on to question the legality of the votes and electoral process of the country that brought him to office just four years ago, the states quietly kept counting the votes.

But the greatness of the maze-like US electoral system ends here.

The US electoral system and the legislators are routinely accused of voter suppression by tweaking registration laws and gerrymandering by manipulating district boundaries to achieve partisan benefits. These would be unimaginable in India with a central election commission watching over every aspect of the elections in the remotest parts of the country.

But the key issue in the US’ electoral college system stems from its deeply decentralised nature. At its core, the US electoral college – the system in place to elect the president – is too decentralised for its own good.

In India, the Election Commission is a constitutional body that oversees polling and counting in every single state. To the envy of the world, the adoption of electoral voting machines (EVMs) has ensured that no fraudulent voting or counting takes place. It’s a clean process, and notwithstanding the seasonal noise (often right before or after an election) about the fallibility of the EVMs, India manages to poll – sometimes even using horses and elephants to facilitate voting in the remote regions – and count its votes seamlessly.

Contrast this with the US system. Here the old-school ballots are still the order of the day. But that’s not it. There are mail-in ballots, post-dated ballots, drop-off ballots, provisional ballots – and most of these are separate categories of votes. What’s more, states in the US have the right to draw their own voting laws, making the presidential electoral system a sum of varied, sometimes conflicting procedures.

If according to one state’s laws, all the mail-in ballot votes must be received by Tuesday – the date of the election — another state could have laws that accept ballot votes by Friday. Furthermore, state laws also dictate when these mail-in ballots can be counted.

So, many of the states that are still counting the mail-in votes actually received the votes days in advance. But their state laws did not allow them to begin counting them until polling was over on 3 November. As a consequence, in crucial states such as Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Arizona, the mail-in votes are still being counted, causing massive delays and, well, anxiety.

Electoral college’s racist origins

There is no advanced liberal democracy in the world that has an electoral system as messy as the US. But the problem with the US electoral college system is more fundamental in nature, which has to do with its deeply racist origins.

Back in the 1780s, when the US constitutional framers were debating how to elect a president, many opposed a direct election. Some of them felt that a direct election would lead to too much democracy, and might result in a demagogue getting elected, who might turn out to be corrupt or deeply undemocratic. The leaders didn’t trust all the voters to vote ‘right’. But the real reason that direct elections were denied in favour of the electoral college was to do with the Southern US states and their slave owners.

Back then, the Northern and Southern US states had almost equal populations. However, just five of the Southern states accounted for 93 per cent of the Black slaves, who had no rights, and obviously no suffrage. So, a popular election for the presidency would have resulted in voting powers dramatically skewed in favour of the Northern states.

Eventually, a bargain was struck, and what came out was the electoral college. It was agreed that only “three-fifths” of the slave population would be counted – though without any voting rights – which gave the South a disproportionate representation in the electoral college.

Almost eight decades later, the Thirteenth Amendment came into being, which outlawed slavery. But the inherently racist electoral college system stayed on. It’s no surprise that even today, presidential candidates with a higher share of the popular vote end up losing the race.

Views are personal.

Subscribe to our channels on YouTube & Telegram

Why news media is in crisis & How you can fix it

India needs free, fair, non-hyphenated and questioning journalism even more as it faces multiple crises.

But the news media is in a crisis of its own. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism is shrinking, yielding to crude prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the finest young reporters, columnists and editors working for it. Sustaining journalism of this quality needs smart and thinking people like you to pay for it. Whether you live in India or overseas, you can do it here.