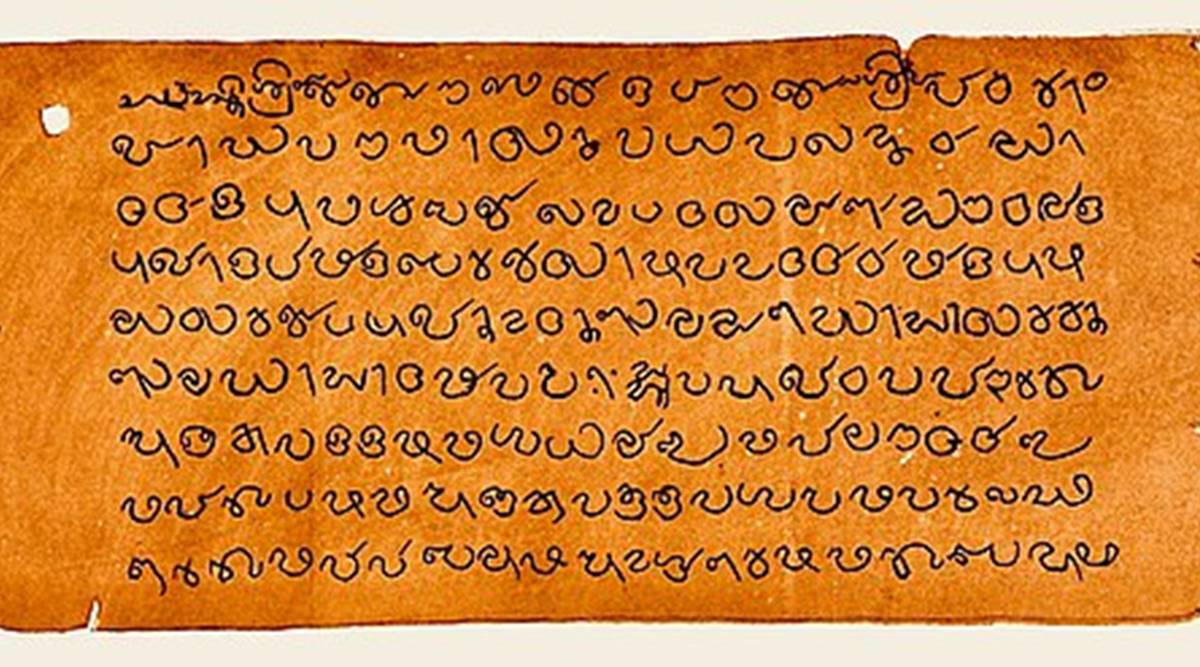

A royal charter in Vattezhuth script issued by Perumal king of Kerala to Joseph Rabban, a Jewish merchant, describing a Jewish colony in Cranganore (present-day Kodungallur) in early 11th century (credit: Sarah Welch/Wikimedia)

A royal charter in Vattezhuth script issued by Perumal king of Kerala to Joseph Rabban, a Jewish merchant, describing a Jewish colony in Cranganore (present-day Kodungallur) in early 11th century (credit: Sarah Welch/Wikimedia)An ancient Dravidian script that’s believed to have flourished for over ten centuries, that ebbed and flowed with shifts in royal dynasties and kingdoms, and is widely accepted as having given birth to the modern Tamil and Malayalam scripts — Vatteluttu, or Vattezhuth, is being slowly salvaged from the annals of history through a concerted effort by researchers, linguists and tech experts in Kerala.

In Kerala, there are innumerable records of the Vattezhuth, or round writing, script in the form of stone inscriptions, edicts and palm-leaf manuscripts that lie waiting to be read simply because there aren’t enough experts who can decode the text. There are a select few living today who have the expertise to handle the script, but their knowledge and know-how remain centralised due to age and various other factors. And so, there remains an imminent danger that if nothing’s done, the historical significance of Vattezhuth and its pointers to our rich past could be lost forever.

It’s in that context that there are now attempts to encode Vattezhuth into unicode so that language experts around the world can learn and understand the script better. Similarly, this week, hundreds in different parts of the world tuned into a virtual seminar series on the possibilities and the historical relevance of Vattezhuth put together by the Malayalam department at St Joseph’s College in Irinjalakuda, Kerala. This is the only college in Kerala and perhaps even in India offering a three-year UGC-approved vocational course in Malayalam and manuscript management in which students learn to understand intricate manuscripts.

“The principal idea is to unify and streamline studies and research around Vattezhuth. A person decoding the script can read it differently from another person. And so, we can get the text right only through regular discussions and exchanges. At the academic level, there is no such opportunity or space. Since we are the only college running a course on manuscript management, we thought we are the right people to organise a seminar series,” said Litti Chacko, the head of the Malayalam department at St Joseph’s.

The first phase of the seminar series, which concluded earlier this week, focused on Malayalam. Subsequent series, later this year, would cast the spotlight on Tamil and Kannada languages, whose origins of the written word also lay in Vattezhuth.

Murukesh S, an assistant professor of Malayalam at the NSS College in Nenmara, said Vattezhuth is believed to have been in use from the 8th century to the 18th century, a period during which some of the finest literature including royal declarations in the entire South Indian region were written.

“This script is proof that it has been subject to changes over generations and old kingdoms getting dismantled and new ones being formed. There have been changes to structures of each letter as time passed,” he said.

“For example, language experts have claimed that the word ‘keralam’ originated from the word ‘cheralam’ meaning land ruled by the Cheras. But when we studied Vattezhuth, we realised that the letters ‘ka’ and ‘cha’ look similar. So the word ‘keralam’ could have been misunderstood as ‘cheralam’. It’s a huge thought. Also, the word ‘keralam’ has found mention in one of King Ashoka’s BC-era edicts. So it could have been some kind of royal name,” added Murukesh, who was one of the speakers at the seminar.

Being a script that was native to the ‘thamizhakam’ region for centuries and used extensively by rulers of Chola, Pandya and Chera kingdoms, Vattezhuth had a politics of its own that rose and fell with regime-changes, he pointed out. Apart from letters, it also had symbols used to indicate amounts of money, timber and rice.

“Today, we cannot read it like reading a newspaper. Sometimes, even a line of the text can take days or weeks to read because it was written 500 or 1000 years ago. Some of the letters are very similar in form. If experts can come together, the process can be easier,” he feels.

“The problem is that knowledge about our prehistoric scripts is not getting decentralised. It’s not reaching everyone. If we have to learn more about our history, culture and lineage, we need to understand the scripts better.”

As part of widening the scope of Vattezhuth research, Chacko said a web portal featuring high-res photographs of inscriptions and manuscripts, is in the works. Following the seminar series, there are also demands from participants for a book that goes beyond an academic level to pack all the information about Vattezhuth.