Are all those accounting-based reported losses are really losses?

The short answer: an emphatic no!

GAAP is a highly deficient, industrial-era accounting system that forces companies to report R&D and other SG&A intangibles as regular expenses.

There's a huge difference between "GAAP losers" and "real losers."

By Feng Gu and Baruch Lev

This is earnings season, and companies reporting losses are a daily occurrence. But even prior to COVID-19, losses proliferated. In 2019, a full 46% of U.S. public companies reported an annual loss, and among high-tech and science-based enterprises losses reached an epidemic level of 70%. And this in the booming pre-Covid economy. A loss creates serious hardship for investors: Popular market multiples, like the price-earning (PE) ratio, are meaningless, and predicting future earnings, or cash flows and their growth from a starting point of a loss is highly problematic. So it’s very important to ask whether all those accounting-based reported losses are really losses. The short answer: an emphatic no!

Consider the software company DocuSign, Inc. (DOCU), which reported a $208 million loss for 2019. DocuSign’s earnings, like those of all U.S. listed companies, were computed after subtracting from revenues R&D ($186 million in 2019) and sales, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses of $727 million. SG&A includes many intangible investments, such as IT, brand enhancement, employee training, etc. These intangible investments plus R&D are, in the 21st century, the main drivers of corporate growth. Only a highly deficient, industrial-era accounting system (U.S. GAAP) can consider such investment to be regular expenses, like interest or wages.

When we capitalize R&D and other intangibles in SG&A (that is, consider these assets, rather than expenses), and subtract from revenues the amortization of the capitalized intangible investments — akin to the accounting treatment of, say, property, plant & equipment — DocuSign’s 2019 accounting loss of $208 million transforms to a profit of $97 million. (Our amortization rate of annual past R&D expenses was 30%, based on the estimated life of acquired software, which usually is three to five years. As for SG&A, we added to earnings one-third of annual SG&A expenses, which is approximately the part of these expenses representing intangibles.)

Accordingly, we can consider DocuSign’s 2019 loss as accounting-driven, and in fact, misleading. For other companies reporting losses, the capitalization and amortization of intangibles often decreases the loss but doesn’t eliminate it. We call these losses “real losses,” in contrast to “GAAP losses.”

Is all this important to investors? Indeed it is. Our recent research (with Chenqi Zhu) on loss-reporting companies — which covers practically all U.S. public companies — shows that of all the companies that had reported annual losses in the past three decades, roughly 40% were, like DocuSign, “GAAP losers.” Namely, they would have reported profits had they been allowed to treat intangible investments as assets. Our soon-to-be-published research clearly shows that the two groups of companies — GAAP losers and real losers — behave very differently in matters important to investors. For example:

Turning losses to profits

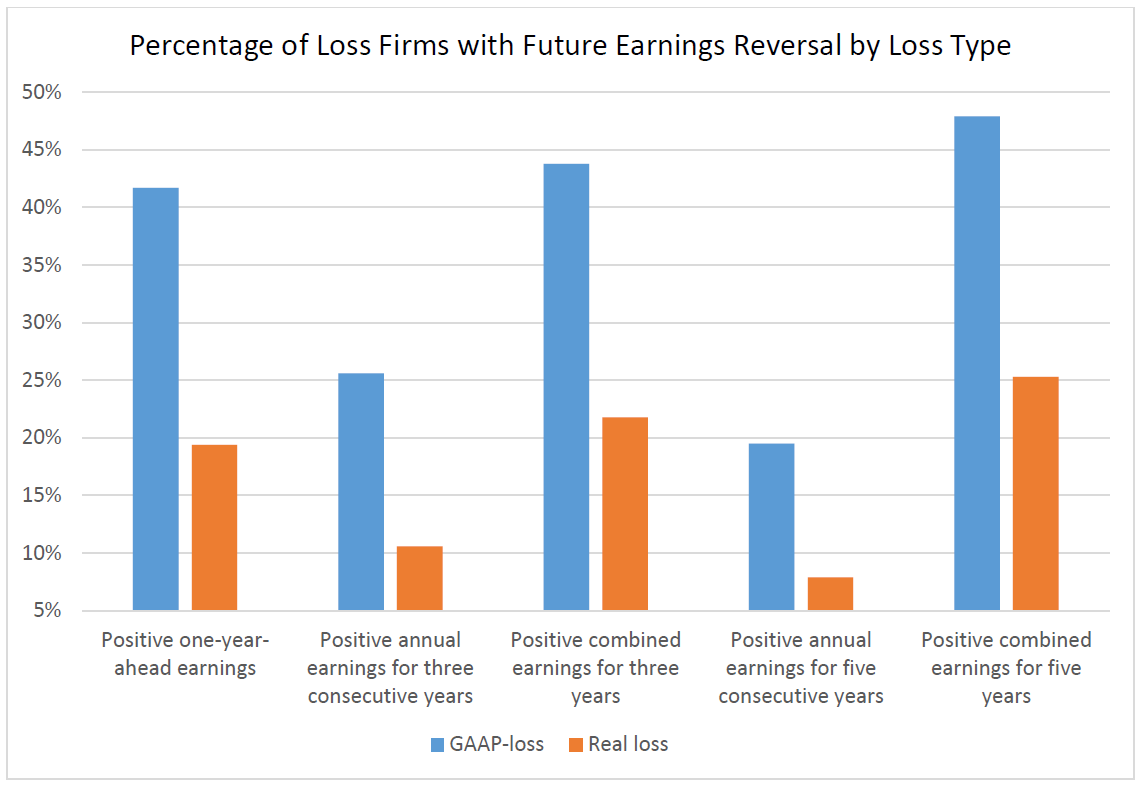

The following figure portrays the subsequent earnings of all companies that had reported a loss in a given year. The two bars on the far left of the figure show that 42% of GAAP losers (companies whose losses would have changed to profits with the capitalization of intangibles) reported a GAAP profit in the subsequent year, whereas only 19% of real losers reported a profit in the subsequent year. That is a significant difference in the future prospects of the two kinds of loss-reporting companies. The second-from-left pair of bars shows that 26% of GAAP-losers report profits for three consecutive years after loss reporting, compared with only 10% for the real losers. And that’s not all.

Source: the authors

Investing in GAAP-losers and real losers

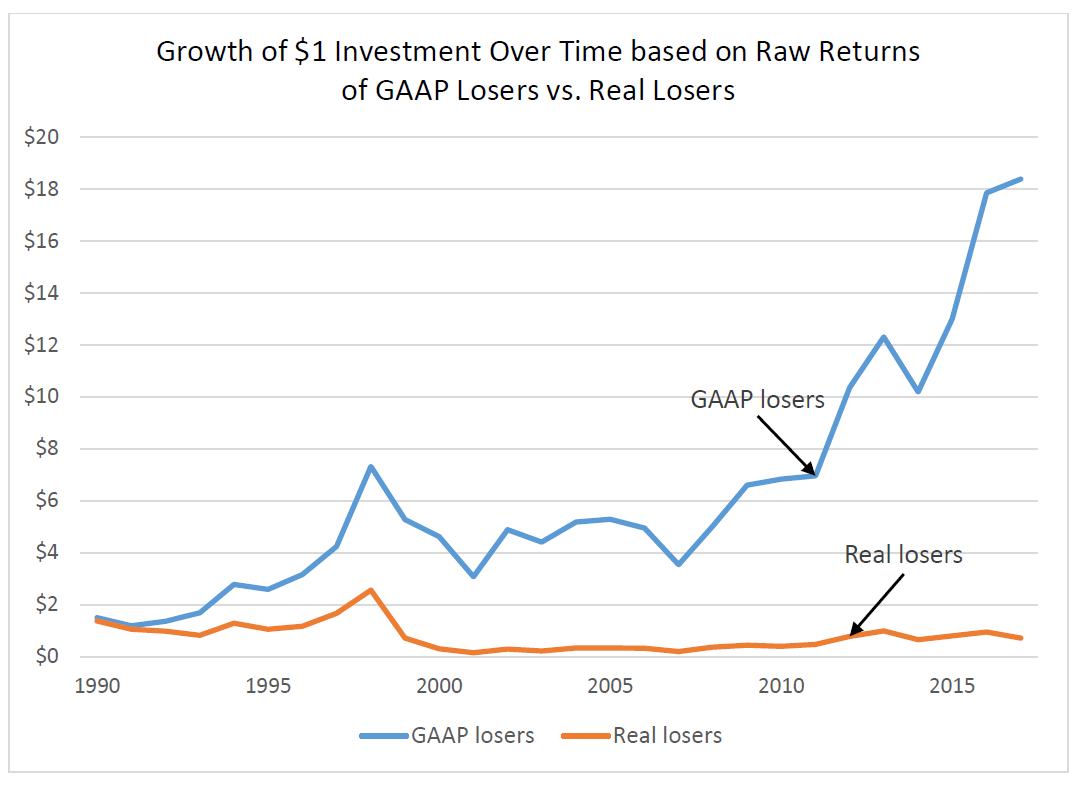

The following figure shows that a dollar invested in GAAP losers in 1990 (with a yearly updating of the investment according to the annual reports of the companies) would have grown to $18 in 2018, whereas a dollar invested in 1990 in the real losers would have gone nowhere over all those years.

Source: the authors

It is important to note that the findings presented in the two figures above are “on average.” There is no guarantee that they will hold for any individual company, like DocuSign.

To summarize, not all companies’ reported losses are born alike. Some are the result of outdated accounting rules, and investment in these GAAP losers should definitely be considered by investors. Other loss-reporting companies — where the loss wasn’t driven by intangibles’ expensing — may require more time and effort to turn operations around. In any case, recognizing the reasons underlying accounting losses is crucial for investment analysis.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.