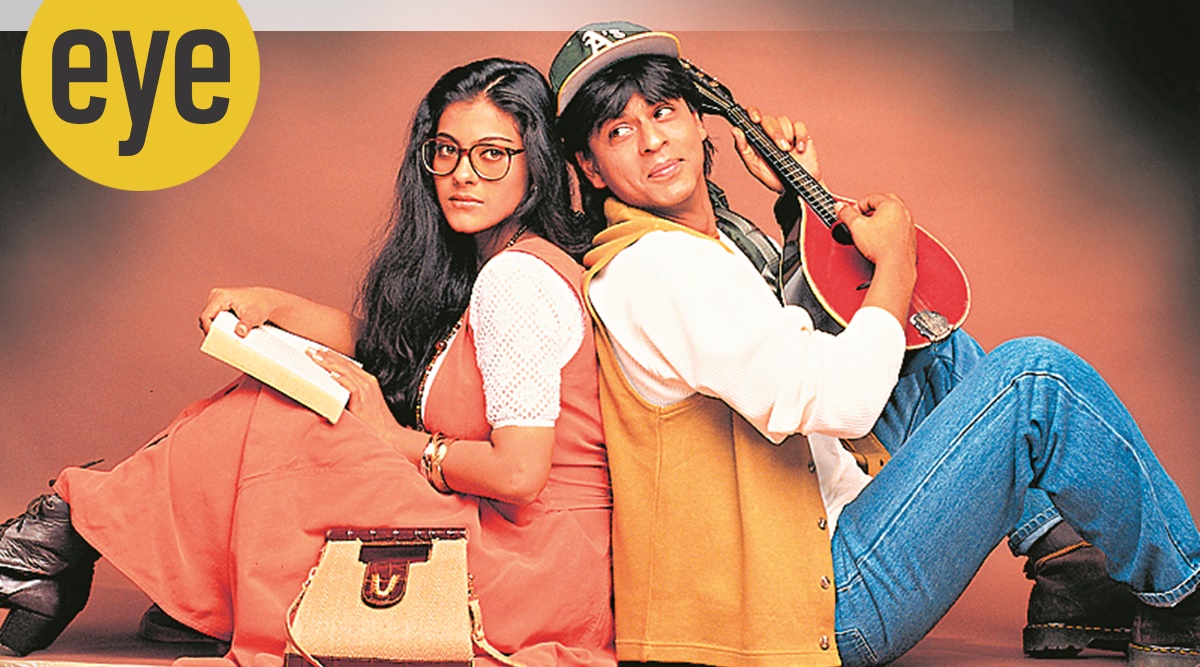

Love, sanitised: Youthful romance was turned into a sanskari, family-friendly construct in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (Express Archive)

Love, sanitised: Youthful romance was turned into a sanskari, family-friendly construct in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (Express Archive)What if Raj hadn’t taken his dulhania away?

I’ve been wondering about this, and a few other things, ever since I watched Aditya Chopra’s debut film, Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge first day first show, on October 20, 1995. It gave us the story of the London-based Raj and Simran, with the tagline “come…fall in love”, and the audience promptly did just that, head over heels. Overnight, Shah Rukh Khan became a superstar, his winsome jodi with Kajol joined the ranks of the ultra-popular pairs of Hindi cinema, and the film turned into a handy short-form for Bollywood romance.

I watched it again last week, and again I was struck by the same feelings that I remember from then, as well as the few re-visits in between: one of abiding freshness, which managed to override the problems, then not as clear as now. A film is always a product of its time, and when we look back, we often forget that crucial fact, of how societal changes colour our view of the past: what was not considered a huge problem a quarter century back is now laden with recently-cemented judgements.

The freshness was evident in the creation of the two young people: Raj Malhotra was a hero Bollywood hadn’t seen before. He was neither a straight-arrow do-no-wrong good guy, nor was he a macho, muscle-flexing fellow: he was silly and callow, at least, to begin with, and the film celebrated both those qualities for him. These are the qualities he holds aloft when he meets-cute with Simran, in the back of a train carriage, where he is much more annoying than cute. It takes a while for the two to spark and sparkle, but once they do, you know it’s a forever thing: SRK and Kajol play really well together.

In that first encounter, Raj is over-familiar, borderline-creepy, crowding Simran into the corner she’s wedged herself in, spouting silly lines in order to impress her. Through the month-long journey through Europe, though, where he, with his group of friends, and she with hers, criss-cross each other’s paths and get to know one other better, he is also revealed as the“susheel, sanskari Adarsh Bharatiya balak”,who will never cross the line. So was Raj the annoying young man who wouldn’t back off when Simran was telling him to, before graduating to easy banter? Or was he this other guy, who would bring his tipsy leading lady back to the bedroom and keep his hands to himself through the night?

The creepiness of that encounter is much clearer today. Back when the film came out, it was just more of the same, where Hindi films mirrored the way young men and women met in the world outside the movies. In a society with practically no opportunities to meet on a level-playing field (Raj and Simran were neither in school or college together, nor were they colleagues), and the only way to “show” a marriageable girl was during a wedding, or other “family” gatherings, young men would hang around outside colleges, or other places where young women would congregate, hoping for eye contact, and more. At a time when even talking to the opposite sex was considered a crime, the chances of young people connecting, and building on those connections were slim to none. And that’s what cinema did, embellishing and exaggerating as it went along: Raj comes off creepy, sure, but is he a creep? Nope, he’s more clown than creep. And the audience watching at that time, could see the difference. No one can love an all-out creep; but can heroes show signs of creepiness? Can we? Of course, we all can. Can we accuse Raj of being a stalker? Not really, and this is where a nuanced view, and an understanding of context, is required. He pursues Simran when he realises that he has fallen in love with her. There’s a difference between stalking and pursuing. SRK had played an out-right stalker in a 1993 film, Darr, also from the House of Yash, directed by Chopra Sr. That “Kkkkk..Kiran” from SRK’s Rahul in Darr, as he stalks Juhi Chawla’s petrified Kiran, still gives me the shivers.

In DDLJ, the essential decency of Raj comes through strongly, and that’s what charmed Simran, and the audience. And that charm has been an abiding factor in Shah Rukh Khan’s long screen journey, along with the fact that we always, at some level, wanted him to be a Raj. What I really hold against the film is its insistence on youthful romance being turned into a sanskari, family-friendly construct. By getting Raj to turn down Simran’s plea of elopement (“Main tumko chheen ne nahin, paane aaya hoon”, declares Raj grandly), an entire generation which included nostalgia-ridden NRIs longing for their roots, as well as modern, “liberalised” desis clinging to their traditions, fell hard for Aditya Chopra’s sanitised version of young love, and a hero who required all-round approvals before taking his dulhania away. So successful was it, that it’s still running in a Mumbai movie-hall, having spawned countless versions of itself in these intervening years. Post DDLJ, the big-budget, starry Bollywood romance got cemented in this template — no rebellion, no giving primacy to sexual longing, all neat and unruffled, all mehendi-and-doli-and-karvachauth.

What, indeed, if Raj hadn’t?