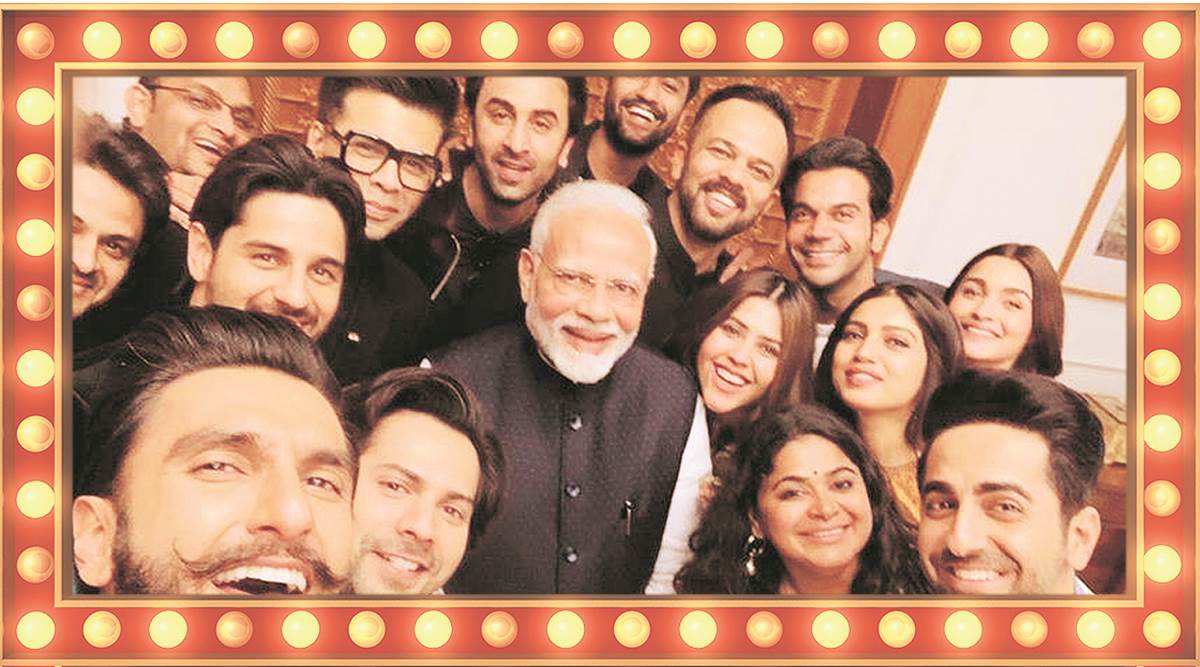

The selfie taken by Ranveer Singh and tweeted by Karan Johar in Jan 2019.

The selfie taken by Ranveer Singh and tweeted by Karan Johar in Jan 2019.On October 2, Karan Johar announced on Twitter that he and some other filmmakers were planning to make “content about the valour, values and culture of India” to mark 75 years of Independence, tagging and thanking Prime Minister Narendra Modi for his “guidance”.

Just days earlier, Johar had made another announcement on Twitter, after one of his employees was arrested as part of an offshoot investigation arising out of the inflating Sushant Singh Rajput death case. He declared he had never consumed drugs, and that he did not know the arrested person. He also threatened legal action against “slanderous” statements.

The employee is now one of 20 held —four are out on bail, including Rajput’s friend Rhea Chakraborty — as part of the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) probe into “the citadel of drugs in Bollywood”.

Johar’s October 2nd tweet was hashtagged #ChangeWithin, a slogan that first started circulating within the film industry last year, when the government kicked off the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. Last October, it appeared at the end of a video on Gandhi by Rajkumar Hirani (whose Munnabhai series was inspired by the Mahatma). The slogan was also the theme of a meeting of Bollywood’s crème de la crème — including Shah Rukh Khan, Aamir Khan, Kangana Ranaut and Sonam Kapoor —with the PM in Delhi in the third week of October 2019, where they thanked the chance to participate in “nation building”.

A year later, Bollywood is battered by Covid-19, with work at almost a complete standstill. But the Rajput case hangs over it as a larger shadow.

This is not the first time the film industry has dealt with blunt instruments of the government — from bans during the Emergency to the Censors, and from Income Tax to Customs. However, it is the first time that it finds itself the target of multiple agencies — the CBI, Enforcement Directorate, and NCB — at the same time. And the first time public sentiments are being whipped up against some of their most popular stars, by TV channels to politicians.

Deepika Padukone at the NCB office.

Deepika Padukone at the NCB office.

It may also be the first time that Bollywood itself is so sharply divided, on largely “pro-government” and “anti-government” lines. One of the more outspoken ones in the latter corner, Anurag Kashyap, is facing sexual assault charges, with the alleged victim on Wednesday getting an audience with Union Minister of State for Home G Kishan Reddy.

Insiders talk of a sense of siege, a question hanging in the air: “Who’s next?”

“It’s an attack on all fronts. Then you know that anything, the Censor Board, everything, is going to work towards pushing you down,” says a filmmaker with several hits under his belt. “We all have slip-ups, especially when making films. Crores go through banks… some accounting mistake. That’s what they’ll use.”

At that meeting with the PM almost exactly a year ago, an actor said about the #ChangeWithin initiative. “Asar dikhega aapko, eik saal, do saal mein (You will see the impact, in one or two years)”. No one knew then it would turn out like this.

***

But, few want to articulate the concerns openly. With the tremors from the Rajput case being felt from Bihar to Delhi to Mumbai, fewer want to go on record.

A filmmaker, who says he “dodged” invitations for that meeting with Modi as well as for a function in Mumbai to meet Amit Shah , points to “so, so many layers” to what is going on. “It’s happening as part of discrediting Maharashtra, attempts to bring down the Shiv Sena-Congress-NCP coalition, for the Bihar polls, and to distract you from other crises in the country.”

Rhea Chakraborty before her arrest.

Rhea Chakraborty before her arrest.

The filmmaker says it’s also happening “because a five-year programme of trying to rein in Bollywood has not shown much results”. “There’s no stronger platform in this country than mainstream cinema… And this has been the rule book of the right wing down the ages.”

Bollywood was taken aback by the attention the Modi government lavished on them in end-2018, 2019. The first such meeting was in December 2018 in Mumbai, with Modi, and Akshay Kumar, Ajay Devgn, Johar, Siddharth Roy Kapur, Ronnie Screwvala and Prasoon Joshi in attendance. They brought up concerns such as the highest GST slab on ticket prices.

Then, in January 2019, Johar along with small-time producer Mahaveer Jain flew a set of young B-town A listers in a chartered plane to meet Modi in Delhi. This time the discussion was on “nation-building”. Ranveer Singh, whose wife Deepika Padukone is among those questioned by the NCB, captured that famous selfie of the PM surrounded by beaming stars. It was four months before the election, and Johar’s Instagram post of the same selfie gushed praise for the PM, and at being invited to contribute to a national project.

The filmmaker says when the Modi invite came, people were scared to say no, but points out that going did not help. “A lot of the people being hit now were a part of that selfie… You can’t pick up the phone and tell Modiji, I was in the selfie, why is my wife being targeted.”

Among the vocal ones is Hansal Mehta, whose critically acclaimed films include Shahid, on the lawyer of the Mumbai riots accused who was killed. He attributes the fear to the film industry’s instinct of “self-preservation”. “We don’t own anything. We make a film and it’s gone. There is an overarching insecurity.”

However, Mehta adds, the belief that if you don’t take sides, you are safe has been broken. “That pretense that we are friends with all… all those who claimed they are apolitical are being targeted… They allow themselves to be used all around. That malleability has led us to where we are today.”

Another filmmaker fumes that big names are “just waiting for an opportunity, ‘to prove ourselves more loyal to the king’, get a CBFC or NSD posting”.

***

A flashback to 2014.The Modi government’s first appointments to film bodies were both controversial — Gajendra Chauhan, the Yudhisthira of Mahabharat TV series, was made director of the FTII, while Pahlaj Nihalani, with among other films Har Har Modi, Ghar Ghar Modi behind him, was appointed Censor Board head. As both choices ran into uproar, did the Modi government realise the lack of top Bollywood names by its side?

The situation has not changed much, despite some recognisable names like Kangana Ranaut, and the two Viveks (Oberoi and Agnihotri, who both make more news off-screen than on) attaching themselves to the government’s coat-tails. Akshay Kumar has lent his name to many of Modi’s projects, and the PM gave a rare interview to him ahead of the 2019 polls.

“Fact of the matter is, you cannot manufacture superstars and you cannot manufacture hits. Or Modi’s biopic (in 2019, with Oberoi in the lead) would have been the highest grossing film… They need the stars, the big directors,” a filmmaker says.

Annus horribilis

According to this filmmaker, the “armtwisting” is not just to get the big names over to their side, but also to ensure a certain kind of cinema. He points to the spree of recent films with the villain a Muslim invader. The latest push is to corner the “liberal voices” that remain. “They are not falling in line with the BJP/RSS narrative. So this is the first direct onslaught… They’re doing it intelligently, because (those targeted) can’t say publicly, ‘Guys, it’s just a joint’. Bharatiya sanskriti mein toh nahin ho sakta hai (This doesn’t happen at least in so-called Indian tradition).”

***

Though the ‘Justice for Sushant Singh’ posters are part of its Bihar campaign, the BJP distances itself from the drug and other charges being thrown at the film industry. “The BJP has no aim to rule Bollywood,” says Maharashtra BJP general secretary Shrikant Bharatiya, while referring to “long-standing political, cultural and ideological associations” with veteran names. “The demand for a CBI probe was made by Rajput’s father. When the drug angle was unearthed, the NCB had to step in. Allegations regarding Rajput’s bank accounts led to the ED probing the matter… Why would the BJP use a sad incident like the death of an actor to seek votes?”

The BJP’s cultural mentor, the RSS, admits it has an “interest” in Bollywood. “Whatever the industry makes, they make for the people of India, and the RSS is interested in whatever is being done for the people of India. But we do not have any intention to control it,” says Pramod Bapat, the RSS in-charge of media relations in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Goa.

Bapat adds, “Vidya aur kala (knowledge and the arts) are meant to open the mind. No one can control it.” However, he says, “It is our expectation, and of the people, that if you are going out into the world as an Indian film, it should carry the fragrance of Indian values.” He insists that while the Sangh supports such films, it could not ensure these are made.

There is no communal agenda to this, says Bapat. “This is absent in our way of thinking. An actor’s religion does not speak about his relationship with India.”

Bopat also acknowledges informal interactions with the industry. “We meet people, speak to them, they also meet us.”

One such meeting took place in September 2017, three months before the Ardh Kumbh in Varanasi. An organisation called the Naimisharanya Foundation organised an event for the RSS attended by senior Sangh leader Bhaiyyaji Joshi, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, then Maharashtra CM Devendra Fadnavis and film industry names such as Subhash Ghai, Madhur Bhandarkar, Sonu Nigam, Kailash Kher and Himesh Reshammiya. It was billed as an exchange of ideas on Indianness, a “Sanskritik Kumbh”.

***

But there is also confidence in the industry that a “takeover of Bollywood” by any one party is impossible — it is made up of just too many moving parts for anyone to hope to bring everyone to heel.

Says the filmmaker who ducked the Modi invitations: “It’s not even really an industry. It’s just a bunch of individuals making films where they can. Producers, directors and actors are only 5%, 95% comprise technicians and workers.”

As for communal dog whistles, those “just won’t work”. “Salman, Shah Rukh and Aamir have genuine fans, and it’s not on the basis of religion,” he says.

Rashid Kidwai, journalist and author of Neta Abhineta — Bollywood Star Power in Indian Politics, says it is talent that counts ultimately. “The industry has been very secular in general. The workforce, musicians, artistes, is an assortment of all kinds of talent from various backgrounds. Even though making the cut is difficult, it is a place for equal opportunities.”

Veteran actor Shabana Azmi questions the nepotism charge levelled at Bollywood following Rajput’s death — the first one, as she points out, followed by murder, money-laundering, and now drug allegations. “Shah Rukh, Ranveer Singh, Vidya Balan, Padukone, Anushka Sharma, Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Rajkummar Rao, Khurrana… have no roots in the industry but are amongst our most successful stars,” she tells The Sunday Express. As for the drugs charge, Azmi says, “Drug addicts? Film stars have never been as physically fit as they are today.”

Shiv Sena MP Sanjay Raut, who had a social media altercation with Ranaut (one of the most vocal proponents of the nepotism claims), dismisses talk of any party capturing the industry. “Bollywood does not belong to any party. Some actors become candidates of a party… go with the party of the Prime Minister. During the Emergency, Sanjay Gandhi attempted to take over Bollywood but failed,” he says.

***

However, if there is any party that is quite entrenched in the industry, it is the Shiv Sena. Bal Thackeray’s association with it began before he founded the party, through father ‘Prabodhankar’ Thackeray, who worked briefly as a publicist with Homi Wadia’s film company in the 1940s. His brother Shreekant is a music director.

In 1968, when the party mounted its earliest ‘Marathi manoos’ campaign, it targeted Tamil films as well as Hindi movies shot in the south. One of the early targets was Dilip Kumar’s Aadmi. But it proved to be the start of a symbiotic relationship.

Until then, say insiders, film producers had to look up to mafia ganglords such as Karim Lala to sort out problems arising from large amounts of money passing hands — especially at that time of licence raj. The Shiv Sena made it more organised, to the extent that its men could paralyse a shooting if their demands were not met.

In 1970, the party formed a wing called the Chitrapat Shakha, to ensure that Marathi films got proper theatres for exhibition. It also stated a distribution arm for Marathi films. These days, it has several unions in the film industry, and has over the years built a relationship with the industry bosses as well — production houses, financiers, directors and stars. By the mid-’90s, Balasaheb’s elder son Bindhumadhav had turned film producer. Daughter-in-law Smita Thackeray served as president of the Indian Motion Picture Producers’ Association from 2001 to 2003.

The Sena’s ties with Bollywood, however, have been transactional rather than ideological. So Bal Thackeray could attack Shabana Azmi and A K Hangal for wanting better relations with Pakistan, but never said a word against Sanjay Dutt, named in the 1993 Mumbai blasts. Dilip Kumar himself went on to become great friends with Balasaheb, till they fell out again, over the Nishan-e-Pakistan honour to the thespian. Shah Rukh’s My Name is Khan faced protests after he spoke about including Pakistani cricketers in the IPL, while Salman Khan’s Tiger Zinda Hai came under its spotlight for leaving very few screens for Marathi releases.

Says Raut: “Balasaheb had very good relationships with all… Rajesh Khanna, Dev Anand, Amitabh Bachchan.” In one famous case, a noted yesteryear actor asked him to help after his daughter started dating a married musician.

In the Rajput case too, the Sena has said there is no foul play, and accused the BJP of politicising his death.

***

The BJP doesn’t shy away from any such political aspirations when it comes to Bollywood. The Modi reign has coincided with movies uncannily aligned with its politics — PM Narendra Modi starring Oberoi (on October 10, the producer announced he would re-release the film when theatres open next week); The Tashkent Files by Agnihotri on Lal Bahadur Shastri’s death; The Accidental Prime Minister showing Manmohan Singh in a poor light; and Uri: The Surgical Strike. 2017 saw Akshay Kumar’s Toilet: Ek Prem Katha, dedicated to Swachh Bharat.

In the social media tirade in the wake of Rajput’s death, one object of insinuations has been Shiv Sena heir apparent Aaditya Thackeray, and his B-town friendships. An unnerved Aaditya put out a statement that he had no connection with the Rajput case.

The Sena sees the entire episode, including the BJP’s questioning of the Mumbai Police investigation into Rajput’s death, as an attempt to destabilise its government, and tarnish the Thackeray name.

“Maybe if Maharashtra had continued to be with the BJP, this would not have happened the way it has. It would have been done more slowly, like earlier, pulling them in, entertaining them, a little bit of pressure,” says the filmmaker.

***

With Johar’s tweet a signal to those outside as well as within that Bollywood has no stomach for a fight, the criticism that the industry’s biggest are not the boldest has got louder. However, a filmmaker defends: “Right now, how does anyone speak? There’s a witch hunt on… The other thing is, what used to give citizens a certain courage, that whatever happens, the media will protect us, where is it today? The media is part of the lynch mob.”

The filmmaker points to an “open letter” by the Producers’ Guild of India on September 4, decrying the “relentless attacks” on the film industry. “It was a very important statement, a very well-worded statement. Did anybody report it?”

Azmi also says Bollywood is being used to distract from the real crises facing the country. “Like Urmila Matondkar said, if the industry is as awful as is being projected, why did the PM ask it to make films on Mahatma Gandhi’s ideology?”

The filmmaker points out that even stars like Aamir and Shah Rukh were targeted after they spoke up about intolerance. “Why is Aamir choosing to keep quiet? He knows that if speaks, nobody’s going to be standing by him. Few people tweeting in support makes no difference.”

Mehta says social media has had a reductive effect. “If Sushant’s death had been debated with greater nuance, politicians could not have used it to divert us from other issues. But we are not open to nuance… The government has realised we want a yes or no. We don’t want a maybe.”

However, Azmi believes, none of this dims Bollywood shine for the hundreds headed to it with stars in their eyes. “Not a chance. The fact is we have never witnessed the inflow of talent we see today… people from small towns, theatre.”

One of them, what now seems a long, long time ago, was Rajput.

Inputs by Zeeshan Shaikh, Vishwas Waghmode, Shubhangi Khapre

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Entertainment News, download Indian Express App.