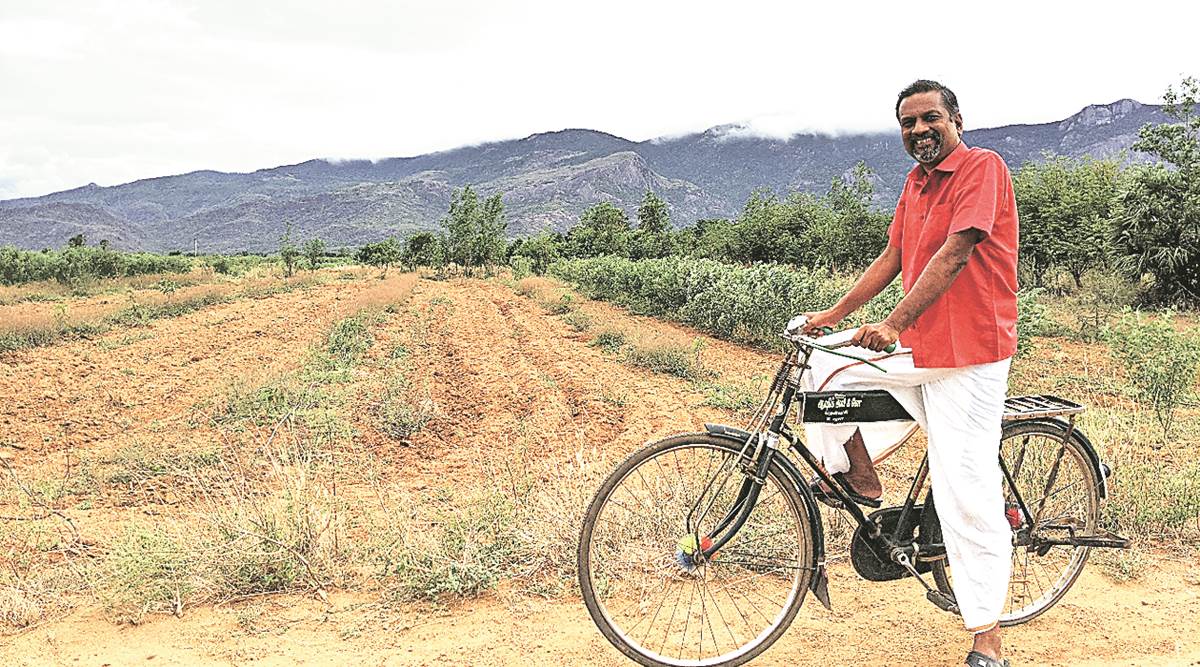

Sridhar Vembu at Mathalamparai village near Tenkasi where he set up a new office and home in 2019. (Express Photo)

Sridhar Vembu at Mathalamparai village near Tenkasi where he set up a new office and home in 2019. (Express Photo)FOR THE rest of the world, Sridhar Vembu is the founder of Zoho Corporation, a Silicon Valley star valued by Forbes at nearly $2.5 billion who decided to take the unusual step of moving to a small village in Tenkasi in southern Tamil Nadu last year. But the man himself says he is more of a teacher these days, wearing the traditional veshti and moving around on a bicycle in Mathalamparai.

What started six months ago as home tuition for three children that took up “about two-three hours” of his spare time, Vembu says he now has four teachers and 52 students in the fold, mostly children of farm labourers from the village.

The 53-year-old is now all set to take this “lockdown experiment” to the next level: “a rural school start-up” that will provide free education and food, a model that doesn’t believe in marks or degrees or conventional affiliations for certificates, or “credentials” as he calls it.

“This has become a serious project. I am also doing part-time teaching. We are trying to put it together as a model now…busy preparing papers, getting necessary approvals,” says Vembu, speaking to The Indian Express over phone from Tenkasi. He is clear though that his “start-up” will not seek affiliation with the CBSE or any other conventional educational board.

It’s not a new template for Vembu. Over the last decade, his Zoho University, a part of Zoho Corporation, has successfully managed the concept of helping Class 10, 11 and 12 dropouts to become IT professionals and team leaders in his own firm and others.

But the challenge in the village, he says, was different after the Covid curbs came into force. “Practically, it was not possible for them to attend classes (online after the lockdown)…some parents had smartphones but cheap models. I had enough time, and we did some physical experiments, I taught them a little Science, Mathematics and English,” he says.

On September 13, Vembu, who is an active Twitter user, posted: “Within few days, my social distanced open air class swelled from three kids to 25 and kids got unruly and I was struggling (smiley) and realised how hard it is to be a teacher.”

“On the ground, what I see is poverty…I noticed that kids coming to our tuition centre are actually hungry. How can you learn anything when you are hungry? That has to be sorted. I appreciate the noon-meal scheme but that is not enough,” he says, adding that his “school” provides two meals a day, and snacks around 4.30 pm, before children are sent home.

According to Vembu, policies made in Chennai or Delhi with good intentions get diluted when they reach villages. “There is not enough ground talent to do the implementation,” he says.

“There are different categories of students among the rural poor. Some who really want to get credentials, and many others who are actually planning to drop out at one point, after Class 8 or 10,” he says. Retaining the dropouts, he says, is the challenge.

In the village, Vembu says, classifying children based on what they know is better than segregating by age. “It is a real start-up challenge,” he says, pointing to children in Class 7 who do not know the English alphabet.

“Another challenge is that teachers do not live in the village. They come and go from a town about 30-40 km away… When people who can afford to send kids to private schools even in rural villages and when teachers of rural schools refuse to send their children there, it is the kids from poorest families alone who end up in the government schools. Their parents may be having a precarious income, they may have jobs only for a few days… Alcoholism is another problem. If a father is drinking heavily, he won’t be bringing the income home and the kid will get neglected, they will go hungry. I see it here,” he says.

Vembu insists that the root of most problems in the education system is “credentialism”. “Even the bright students focus only on grades, not the knowledge they acquire. There are many non-traditional learners. They are among us, in our families. We know them, they are brilliant but the exam results will not show that. The system should accommodate non-traditional learners too, those who fail in exams but still do the best in jobs,” he says.

Before the school, Zoho, which clocked an operating revenue of Rs 3,300 crore in financial year 2018-19 with more than 50 million clients, opened over a dozen rural offices in Tamil Nadu during the lockdown to take software engineers back to their villages.

“My only demand was to set up offices in rural areas. They decided the locations. We will open 10 more offices in three months, opening more in Tamil Nadu as well as Kerala and Andhra, each with a seating capacity of up to 100 people,” he says.

In Mathalamparai, Vembu says, he has made many friends over the last year visiting tea shops and playing cricket with children. “They were very warm. They were curious but still very friendly to a stranger,” he says.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest India News, download Indian Express App.