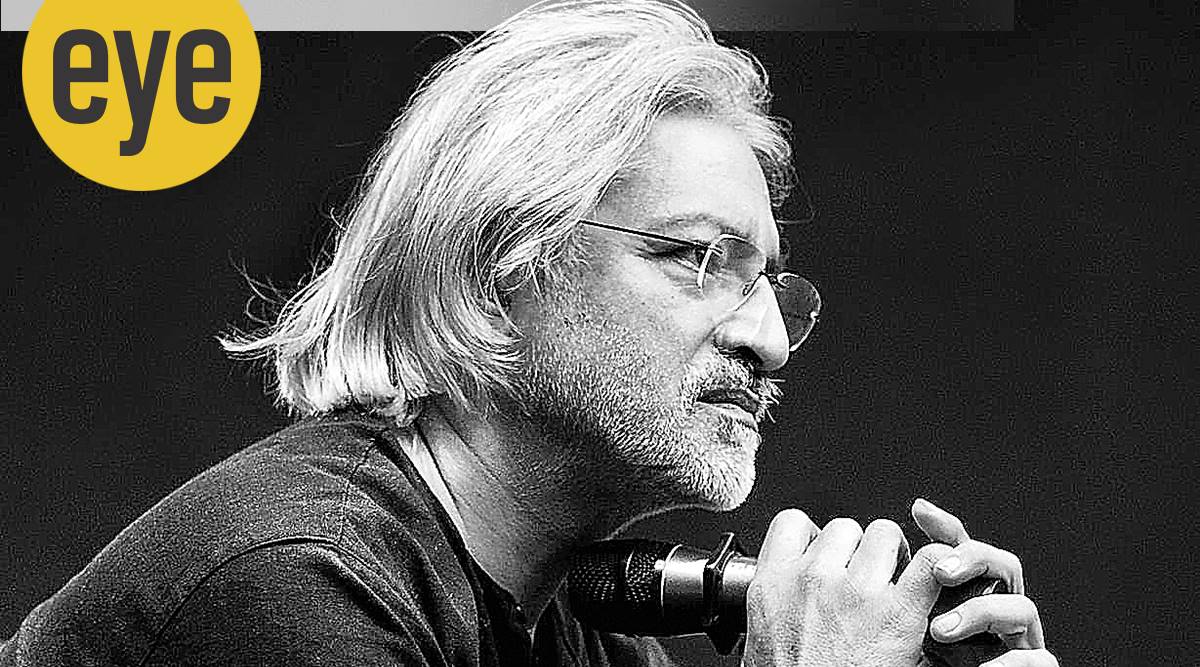

Anant Patwardhan

Anant PatwardhanYou are almost as old as independent India. Were you a ’70s ‘angry young man’ who was making films to channel his anger?

While on a scholarship in the US, I first filmed anti-Vietnam war protests that landed me in prison twice. On returning to India in 1972, I joined a voluntary rural development and education project in Madhya Pradesh, then moved to Bihar in 1974 when the JP (Jayaprakash Narayan) movement began and picked up the camera again to record police violence. Our film Waves of Revolution (1974) went underground in 1975 during the Emergency. I later made a film on political prisoners (Prisoners of Conscience, 1978). So the journey began.

Cinemapreneur.com is screening Jai Bhim Comrade (2011), and a docu-short Heart to Art: Across Borders (2020), completed during the lockdown, using footage of an India-Pakistan art exchange you shot in 2004. What do you make of such platforms?

They are very welcome. At first, we lugged heavy 16 mm projectors and even generators to venues where electricity was scarce. During the video era, equipment became smaller, and now, in the digital age, new possibilities emerge. But the problem of how to attract eyeballs remains. Today, the internet is oversaturated and attention spans tiny but every new initiative is good.

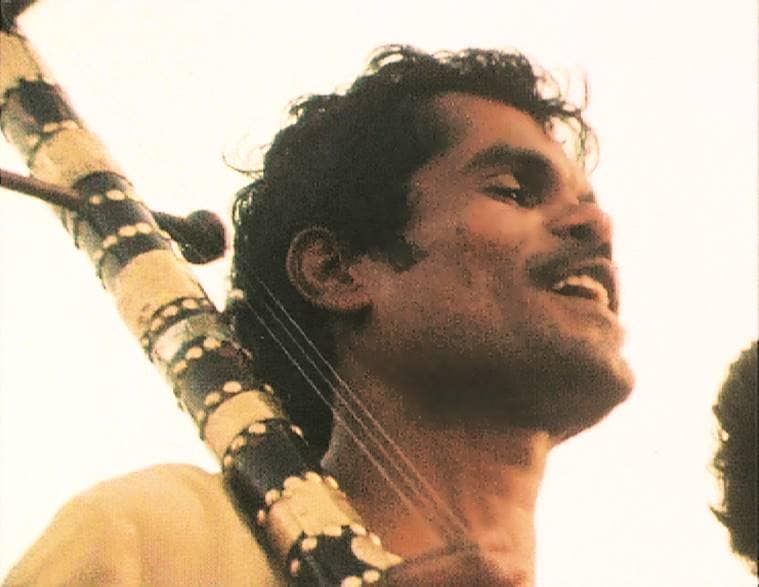

Speak out, sing out: The late Dalit poet-activist Vilas Ghogre in Jai Bhim Comrade

Speak out, sing out: The late Dalit poet-activist Vilas Ghogre in Jai Bhim Comrade

Jai Bhim Comrade features the only documented song of Dalit poet-activist Vilas Ghogre (who hung himself to protest the death of 10 Dalits in the 1997 Ramabai Colony police firing). Did you know him? It also features the Kabir Kala Manch (KKM), whose members were recently re-arrested.

I met Vilas in the early 1980s when we fought against illegal slum demolitions. The song in Jai Bhim Comrade was first shot when Bombay: Our City (1985) was made. I recorded many of his other songs but filmed just one. Vilas’s protest suicide shocked me into looking at the extent of atrocities on Dalits and to explore their poetry of resistance. The film took 14 years to make and includes a range of amazingly powerful storytellers. KKM was one such. When they were hounded by the police, we helped them face trial. They were finally granted bail by the Supreme Court in 2017. Today, they are charged for visiting Bhima Koregaon while upper-caste alleged instigators of violence like Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote walk free.

You have expressed disappointment in Prashant Bhushan’s contempt verdict. His fine of Re 1 was criticised as being pro-savarna as the same treatment wasn’t extended to Dalit judge CS Karnan in his 2017 contempt case.

Speaking out against an authoritarian, majoritarian, casteist system is necessary. Whether it’s a Bhushan or a Karnan, all resistance is bravery.

You’ve struggled against censorship for long. Aren’t your detractors tired of you?

We won seven court cases–once to get a Censor certificate for War and Peace (2002), the rest to force Doordarshan to broadcast my films that had won National Awards (Bombay: Our City;In Memory of Friends, 1990; Ram ke Naam, 1992; Father, Son, and Holy War, 1994, the latter going to court three times). Advocate (PA) Sebastian in the high court and Prashant Bhushan in the Supreme Court ensured the telecasts. Arguing pro bono, they never allowed the state to cut a single frame.

Recently, you and documentary filmmaker Pankaj Rishi Kumar petitioned the Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF) against dropping your respective films, but then withdrew.

Few judges today have the backbone to rule against the state but we still wanted to test the waters. Reason/Vivek (2018) had won top prize at IDFA (Amsterdam), one of the best-regarded festivals in the documentary world. Pankaj’s film (Janani’s Juliet, 2019) had won the top prize at (IDSFFK) Kerala. Both films had qualified for the Oscars. But after lecturing the government against censorship, the judge indicated that he would not interfere with MIFF. So, we withdrew rather than set a losing precedent. Press coverage did, however, expose the blatant backdoor censorship.

Father, Son and Holy War speaks of our culture of machismo (touching upon Roop Kanwar’s sati in 1987). Does the hounding of actor Rhea Chakraborty illustrate this?

Of course! Apart from the media lynching, when all else failed they caught Rhea for marijuana! Then, why is bhaang sold at temples? What do sadhus imbibe?

‘Unlike religion, which believes in a final truth, science is an endless search for truth,’ said the rationalist, the late Dr Narendra Dabholkar (shot dead in 2013) featured in Reason. Is the assault on reason exclusively true of today?

Religion and blind faith have dominated the world for thousands of years. The Age of Reason dawned in the West around the 16th century but in India, Charvaka and the Buddha were early advocates.

Doordarshan’s 1997 telecast of your Ram ke Naam (on the Babri Masjid demolition) saw a heated Rajya Sabha debate, and even today the film’s screenings are disrupted. How do you react to the Ayodhya bhoomi pujan and the court verdicts?

Ram ke Naam was submitted as evidence before the Liberhan Commission looking into the Babri dispute. Obviously today’s courts have ignored it. Our constitutional law has been replaced by a Hindutva version of sharia law.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Eye News, download Indian Express App.