As Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor's ancestral home in Peshawar is all set for a facelift, we look at Bollywood's relationship with Pakistan. (Express archive photo)

As Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor's ancestral home in Peshawar is all set for a facelift, we look at Bollywood's relationship with Pakistan. (Express archive photo)Quaint in character and Sufi in spirit, Peshawar was once Dilip Kumar’s home. Or “lost city,” as Salman Rushdie might call it. On September 30, the god of acting urged his Pakistani fans to share pictures of his decrepit former ancestral address in Peshawar’s Qissa Khwani Bazaar — literally, a storyteller’s market in a historic city that has unfortunately gained some notoriety in recent decades. The Taliban, terror, jihad and bombing with the BBC even dubbing it ‘the birthplace of al-Qaeda.’ Yet, in 1922 when Yousuf Khan was born there (he was later reborn in Bollywood as Dilip Kumar), the Northwest Frontier was a different place altogether and very much a part of undivided India. These days, the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa state government has been focussed on preserving the historic homes in the walled city and the most prominent of these are situated in the bustling Qissa Khwani Bazaar. This neighbourhood has a rather special connection with Bollywood. Not just Dilip Kumar, Hindi cinema doyens Prithviraj and Raj Kapoor also trace their origin to this part of Peshawar. The iconic but ramshackle Kapoor Haveli was rumoured to be built between 1918-1922 by Kapoor’s grandfather Dewan Basheswarnath. Shah Rukh Khan’s family also hailed from Qissa Khwani Bazaar. Some say one of his paternal uncles owned a shop there until recently. If all goes well, the Pakistani government will rescue this forgotten cultural heritage and hopefully, turn the dusty homes of the Kapoors and Kumar into a shrine for movie-goers.

Thank you for sharing this. Requesting all in #Peshawar to share photos of my ancestral house (if you’ve clicked the pic) and tag #DilipKumar https://t.co/bB4Xp4IrUB

— Dilip Kumar (@TheDilipKumar) September 30, 2020

The news was enough to send Dilip Kumar, now 97, on a nostalgic trip. In a series of tweets, on October 1, the thespian shared fond memories of Qissa Khwani Bazaar, a place that he believes has influenced his craft and style. Commenting on the simpler Peshawar times in his memoir The Substance and The Shadow, the nonagenarian notes that “childhood images cling to the subconscious surreptitiously and they emerge before your eyes like an unexpected visitor through the backdoor to give you a lovely surprise.” Indeed, when Kumar’s family (his father was a successful fruit merchant in Peshawar who scorned the idea of his son entering a disreputable profession called the movies) moved to Nashik’s Deolali, the picturesque setting gave him both “creative impetus” and much-needed solace after losing Peshawar.

Homes Left Behind

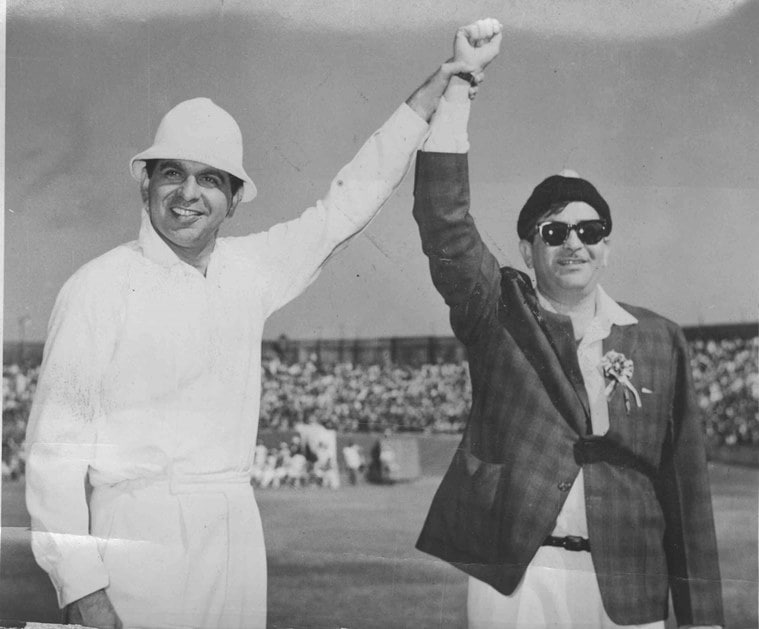

The ‘mythical’ Peshawar was central to Dilip Kumar’s lifelong friendship with Raj Kapoor. (Photo by K G Samel)

The ‘mythical’ Peshawar was central to Dilip Kumar’s lifelong friendship with Raj Kapoor. (Photo by K G Samel)

The ‘mythical’ Peshawar was central to Dilip Kumar’s lifelong friendship with Raj Kapoor. Famously, the two Bollywood giants were neighbours across the border. Their families knew each other well, as Kumar’s dad was friends with Dewan Basheswarnath (Prithviraj’s father, a police official) and it is said that Kumar and Raj Kapoor, who continued to remain close despite becoming superstars in their respective ways, often reminisced of their childhood days. “He was a born extrovert and charmer,” that’s how Kumar described his best friend. Decades later, in 1990-91 during the making of Henna, Rishi and Randhir Kapoor dropped into the now century-old Kapoor Haveli. Back to their roots, they were “received in our street like royalty and were later feted at the provincial governor’s mansion,” according to the Pakistani columnist Mohammed Taqi.

Along with Kumar and Kapoor, the late Dev Anand had formed a troika that reigned golden-age Bollywood. It should not surprise you that Anand also had strong roots in Pakistan having spent his formative years in Lahore. It’s a city, he reflected in later interviews, that shaped him most. Born in Punjab’s Gurdaspur to a well-to-do lawyer, the evergreen star majored in English literature from Government College, Lahore. In 1943, he left Lahore with “only Rs 30 in his pocket and a stamp collection,” travelling by Frontier Mail on his way to Bombay to try his luck in Hindi cinema. Later, the flamboyant star of Taxi Driver and Guide got a chance to revisit Lahore with the late Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in the famous peacemaking bus ride from Wagah that the latter billed as a new chapter in the often-fraught Indo-Pak relationship. On the other side of LoC, a carnival atmosphere awaited the Indian delegation.

Horrors of Partition

While Vajpayee and Nawaz Sharif were rewriting history, Anand — indefatigable as ever — was toying with the idea of making a film in Pakistan. As he announced to journalist Rajiv Bajaj, in his typical flourish, “There’s no reason why a great film can’t be made in Pakistan by Dev Anand on a tremendously human angle without any propaganda in it.” The film never really took off, which must have sounded like music to the ears of hapless viewers who had to bear the brunt of latter-day Dev Anand clunkers like Censor and Love at Times Square. Jokes aside, if Dev Anand had an emotional joyride in Lahore as he toured his alma mater mobbed by news photographers and fans, the people of Pakistan returned the favour. When Anand died in 2011, Pakistani fans mourned the loss as one of their own. Ditto with the death of Rishi Kapoor, earlier this year.

Balraj Sahni, a decade older than Anand, was also a Government College alumnus. The Do Bigha Zamin stalwart originally hailed from Rawalpindi where, recalls his son Parikshat Sahni in The Non-Conformist: Memories of My Father, the family kept a pre-Partition mansion as “our winter home.” It is worth remembering that it was Balraj Sahni’s brother Bhisham Sahni who wrote one of the most powerful Partition novels in Tamas, later made into an era-defining Doordarshan series by Govind Nihalani. Another Partition victim is Gulzar. Memories of his hometown Dina (Jhelum) still haunts the veteran lyricist who best summed up the horrors of 1947 in his famous poem Dastak as, “Sarhad par kal raat suna hai, kuch khwaabon ka khoon hua hai.”

Punjabis (like Kapoors, Sahnis or Anand brothers) ruled the 50s Bollywood and Sunil Dutt was one of them. Like Gulzar, he was born in Jhelum and maintained close ties with his native place, so much so that once when he visited his village Khurd, the locals overwhelmed him by suggesting that his ancestral land “still belongs to you” and that he can have it all back whenever he returns. In 1998, he did agree to accompany Dilip Kumar when the acting legend was honoured with Nishan-E-Imtiaz, Pakistan’s highest civilian award shortly following which a huge controversy erupted with Shiv Sena demanding the Mumbai-based Kumar to return the award. Some of the hue and cry was understandable — even expected. Sentiments always run high on both sides. More than 70 years after the acrimonious split the republic of Gandhi and Jinnah still don’t see eye to eye. What else to expect in nations where even a game of cricket is like going to war? Since Partition in 1947, Pakistan’s relationship with India has only gotten worse. Kashmir has been the most important bone of contention. But our hostile neighbour’s role as a chief terror sponsor and the border skirmishes have further harmed the situation, than healing it. The nuclear-armed states have come to blows, more recently in Pulwama. Under PM Narendra Modi, it can be argued that we have taken a more belligerent approach towards Pakistan for which he has won praise in some quarters. Yet, Modi’s rise has sparked a wave of jingoism previously unseen in India. Especially to Indian Muslims, ‘Go back to Pakistan’ has become the Hindu hardliners’ standard refrain. Still, optimists hope that the Mahabharat-style dispute between the warring cousins will end someday. Would it be cliche to say that ordinary citizens in both countries want peace? We don’t know Pakistan, but speaking of India, even political propaganda has not stopped some Indians, especially elite Punjabis, from romanticising about Pakistan. This, one assumes, is the Pakistan of Faiz, Iqbal and Manto.

Fast forward to 2020, Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor hark back to a time when the two nations were one. As a result, they form a crucial link to the two cultures. When Kumar decided to keep his Nishan-E-Imtiaz, despite the political protests, he reportedly wrote to AB Vajpayee countering that if the PM “thinks that the award injures or lowers the prestige of India then I will surrender it.” He never did. And now, with news coming in of his Peshawar home being turned into a museum, it can be said that life has come a full circle. Probably, it will spell some catharsis to boot.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Entertainment News, download Indian Express App.