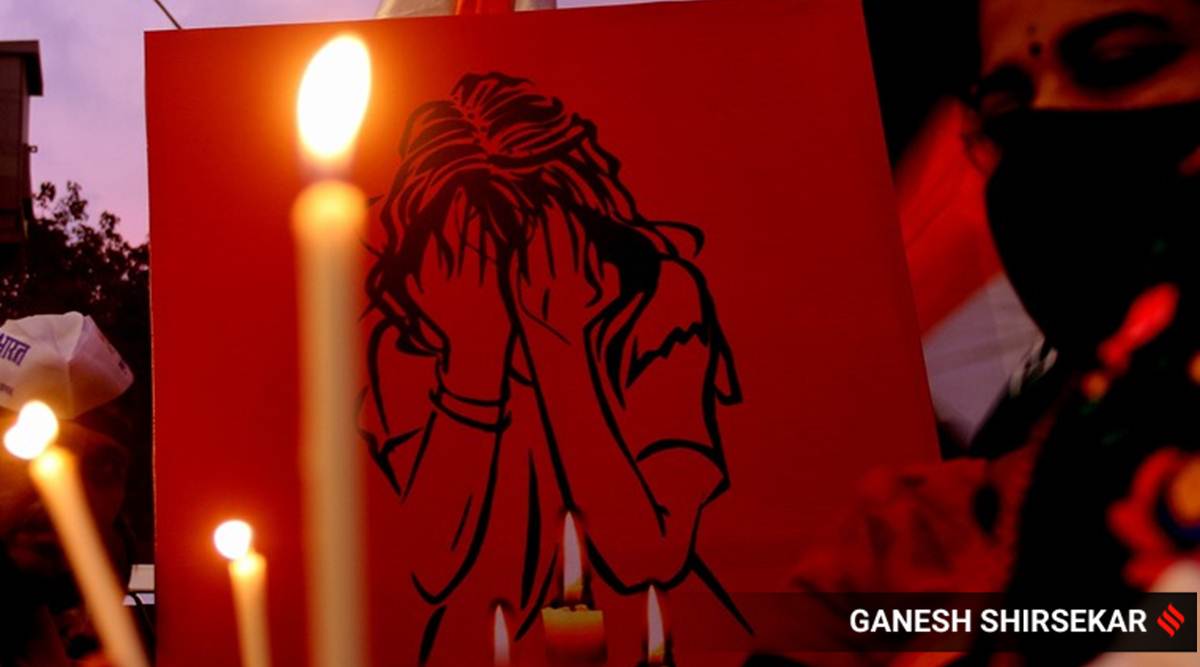

A candle light march taken by the Mumbai Congress unit in the city to protest against the Hathras rape case on Friday. (Express photo by Ganesh Shirsekar)

A candle light march taken by the Mumbai Congress unit in the city to protest against the Hathras rape case on Friday. (Express photo by Ganesh Shirsekar)On September 14, 2020, a 19-year-old Dalit woman goes to work in the fields, close to her home, in the Hathras district of western Uttar Pradesh. Let us call this young woman — India. She lived with her family across the street from their upper caste Thakur neighbours in this bustling town, that is 200 kilometres from Delhi.

As Newslaundry reports, India’s mother found her daughter’s body in the part of the fields owned by the Thakur neighbours. She is quoted as saying, “My daughter was lying naked with her tongue protruding from her mouth. Her eyes were bulging out and she was bleeding from her mouth, her neck and there was blood near her eyes. I also noticed bleeding from her vagina. I quickly covered her with the pallu of my saree and started screaming.”

The law is clear on how the state must respond. At this point, a First Information Report (FIR) must be immediately lodged, and if the victim needs hospitalisation then the requirements of a medico-legal case such as this, the preservation of clothing, the recording of injuries, can be done at the hospital. A statement as to the events, under Section 164 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, of the survivor in the presence of a magistrate, must be ensured by the police. It is expected that the police arrange for the magistrate to be taken to the hospital. Finally, if the survivor of the rape should pass away, then the body must be handed over to her family, after post-mortem analysis. Now let us examine what happened to India and her family.

Post the assault, India was taken to the Champa police station, and from there to the hospital while her brother stayed back to register an FIR. At the hospital, despite the trauma on September 21 and 22, she clearly named her upper caste neighbours and their friends as her assaulters. Eventually, belatedly — over two weeks after the assault — India was transferred to Safdarjung Medical Hospital in Delhi, where she died. A magistrate came to the hospital in Aligarh to record her statement but it is unclear whether they preserved sufficient evidence for a case such as this.

What followed subsequently, tells you even more about the state of Uttar Pradesh police and those they answer to; by chain of direct command, to the Home Minister of the state — that portfolio is held by Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath. After her death in Delhi, India’s body was whisked away, and despite the fierce protests of her family, was cremated around 2:30 am/3:00 am by the police. The journalist Tanushree Pandey in her first-person account, captures the police telling India’s family that mistakes have been made (galtiya hui hai) but it is time to “move on”, and family members locked themselves in their home in fear while police proceeded to cremate India. The police then tried to prevent the press from taking any pictures or recording their actions.

Meanwhile, on October 1, the Additional Director General of Police, Prashant Kumar, apparently relying on the FSL, said that India’s cause of death was injury to the spinal cord, no sperm was found and no rape occurred. The officer would do well to note Section 166 A of the Penal Code that makes it a punishable offence for the police not to register a rape.

That the body was cremated in a hurry makes it easier for him to spin this story. Reports indicate that the FSL samples were taken days after the events, making it impossible for bodily fluids like sperm to be found. However, the amendments to our rape law mandate that only penetration is required to establish rape or gang rape, and not presence of sperm. Further, the nature of the injuries, repeated statements by India, make the gang rape clear.

The Allahabad High Court, on October 1, 2020, shaken by the course of events, has taken suo motu cognisance of the events — in Re: Right to decent and dignified last rites/cremation. The judges point to case law that mandates that the right to dignity and fair treatment is available to all in life and death. A decade ago, they had declared that the right to life and dignity includes the right of a deceased to have her body treated with respect, subject to her tradition, culture and religion practised. The next date of hearing before the High Court is October 12, meaning that India’s family must withstand the pressure being mounted on them to change their story.

The historical reality of our country is that events like the gangrape of India have been routine. In pre-constitutional feudal India, there was socially sanctioned control of the upper castes on the labour, bodies and aspirations of lower castes, especially Dalits. Our Constitution, recognising the systemic degradation of lower caste persons, mandated prohibition on caste and sex based discrimination. It also made reparations by providing for reservation in educational institutions, political constituencies and public employment for members of Scheduled Castes and Tribes.

But India’s case shows that no constitution has any meaning if those tasked with enforcing it have aligned themselves to an unconstitutional caste-based code of loyalty. As Cynthia Stephen, a Dalit activist and writer, asks, “Why on earth was her body torn from the family and burnt in the dark somewhere like it’s a piece of trash? In Bangalore our garbage trucks take the solid waste outside the city and incinerate it in an open field. This is something like that, no dignity even in death.”

India’s violation is part of a larger story of our country. It is not just India’s spine that was broken — it is the spine of the Indian state and the police that is fractured. It is not just India that was brutalised, it is each and every woman who is raped and silenced that screams out loudly. In the disregard of India’s body even in death, it is our collective dignity and decency that is erased forever. Shame on all of us.

The writer is a Senior Advocate at the Supreme Court of India.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App.