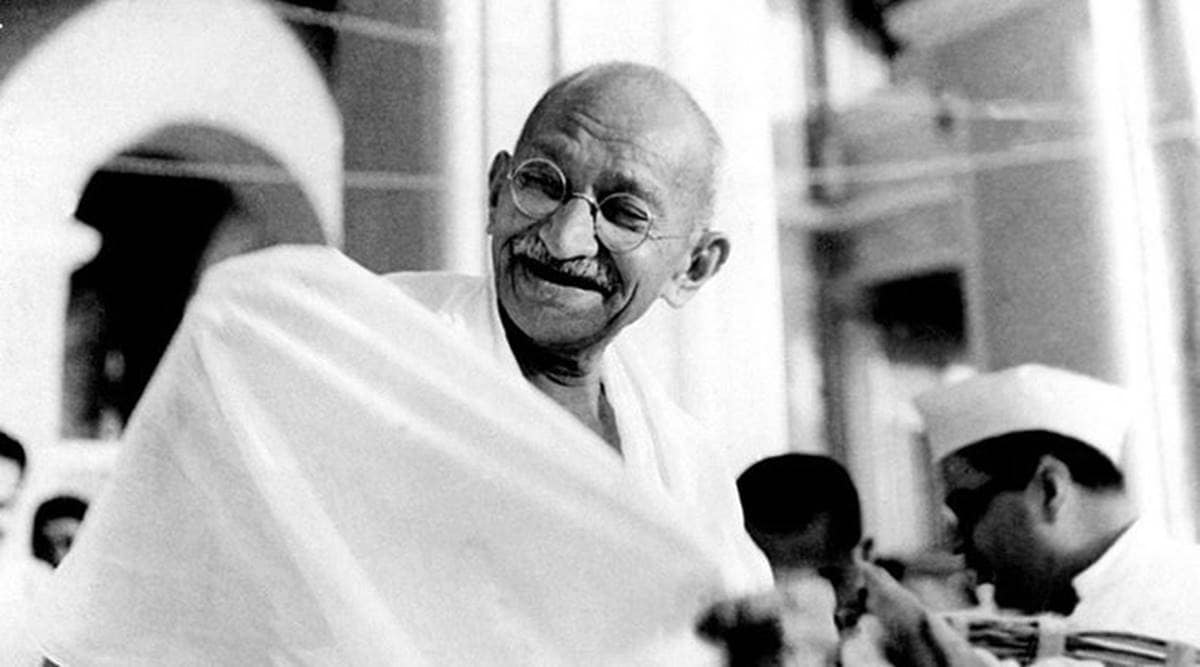

Mahatma Gandhi.

Mahatma Gandhi.For Gandhi, violence was a sign of the failure of a legitimate political power. At the core of Gandhi’s political theory is the view of politics as shaped by internal moral power, rather than from the standpoint of rational violence. Consequently, for Gandhi, the modern state contained forces that threatened, rather than enhanced, liberty. Therefore, he did not consider democracy as a political regime but as a value, which needed to be created and cherished. His defence of institutions of the liberal constitutional state did not mean that he justified them in terms of his political philosophy. To the contrary, politics for Gandhi was an act of consciousness, not a mode of living taken for granted.

Gandhi did not see the goal of political action as the immediate capture of office. According to him, the basic condition of political action was the elimination of violence. His principal aim was to civilise modern politics from within, by shorting the circuit of resentment, hatred and coercion. His politics of non-violence was a method to mobilise collective power in a manner that attends to its own moral education in an exemplary and innovative way. Excellence is the end that we have to set before ourselves as political beings. Gandhi showed that a life of excellence is an agency and a transformative force, an experience of conscience underpinning the harmony between ethics and politics.

An “ethic of responsibility” underlined Gandhi’s non-violent politics. He argued for a dedicated and committed political ethos, which did not accept the necessity of “dirty hands” in politics. As he affirmed on July 3, 1940, “I have always derived my politics from ethics or religion and my strength is also derived by my deriving my politics from ethics. It is also because I swear by ethics and religion that I find myself in politics. A person who is a lover of his country is bound to take a lively interest in politics.”

Gandhi was thinking in terms of long-term social stability among nations. So, he wanted to put his hands on the wheel of history through non-violent politics. Ultimately, what was important for him was to move from violence to politics. This transition could not take place without the intervention of the ethical in the political. In a speech at All-India National Education Conference on January 13, 1930, he observed: “There are some who think that morality has nothing to do with politics. We do not concern ourselves with the character of our leaders… If swaraj was not meant to civilise us, and to purify and stabilise our civilisation, it would be worth nothing. The very essence of our civilisation is that we give a paramount place to morality in all our affairs, public or private.”

The Gandhian appeal to the ethical in politics was not only a way to seek Truth, but also of coming to know oneself in ever-greater depth. The Gandhian effort for non-violent politics was a cultivation of one’s capacity for ethical citizenship. That is to say, Gandhi considered politics as a work of the heart and not merely of reason. This recalls French philosopher Blaise Pascal, who said: “The heart has its reasons which reason itself does not know.” In the same manner, Gandhi believed that the heart, and not reason, is the seat of morality. He wrote in Harijan (June 8, 1940): “Morality which depends upon the helplessness of a man or woman has not much to recommend it. Morality is rooted in the purity of our hearts.” Gandhi believed that next to constructive work, a society needs also to be inwardly empowered, since human beings are capable of love, friendship, solidarity and empathy.

On January 5, 1907, Gandhi wrote in Indian Opinion: “It is the moral nature of man by which he rises to good and noble thoughts. The different sciences show us the world as it is. Ethics tells us what it ought to be. It enables man to know how he should act. Man has two windows to his mind: Through one he can see his own self as it is; through the other, he can see what it ought to be.” Consequently, Gandhi insisted on the autonomous nature of the moral act. His view of morality was not a denial of politics. On the contrary, Gandhi’s moral idealism was completed by a political realism, which sought the construction of a democratic society. He wrote: “I feel that political work must be looked upon in terms of social and moral progress.”

From Gandhi’s perspective, non-violence was an ontological truth that followed from the unity and interdependence of humanity and life. Therefore, he advocated an awareness of the essential unity of humanity. That awareness called for critical self-examination and a move from egocentricity towards a “shared humanity.” This “shared humanity” cannot exist if it is not aware of its shortcomings. It needs to strive to remove its ethical imperfections in order to be able to live with global challenges. In an age of increasing “globalisation of selfishness”, there is an urgent need to understand and practise the moral leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and re-evaluate the concept of politics.

The writer is director, Mahatma Gandhi Centre for Nonviolence and Peace Studies, O P Jindal Global University

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App.