The language of the book is playful and unserious.

The language of the book is playful and unserious. In one of my favourite stories in The Women Who Forgot to Invent Facebook and Other Stories, a dance teacher stands on the slippery floor of a green room and shouts down a frightened shishya, “When you do that mudra, you are supposed to look like you are opening a small sindoor box, not your father’s suitcase!” The scene is a college festival in Thiruvananthapuram, where our heroines, three young women who are quite certain they are “goddesses”, have arrived to conquer. A forcefield of glamour and supreme confidence sets them apart from pretenders. “Unlike most of the ground-kissing, terrified Bharatanatyam dancers, we liked to dance for fun.”

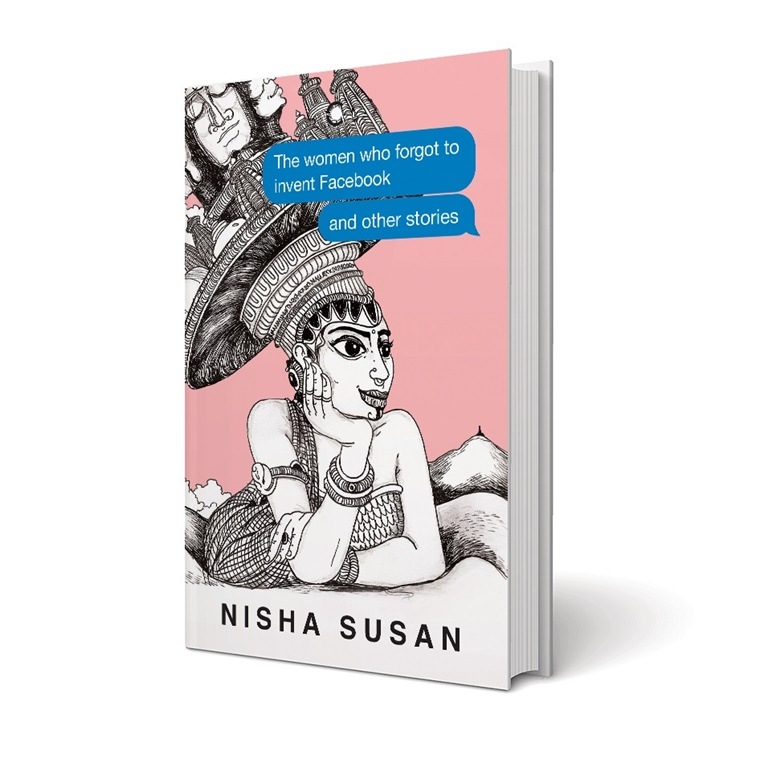

With its crackling style, an eye-popping cover and a gallery of twisted characters, Nisha Susan’s debut collection of stories is somewhat like the women of ‘Trinity’ — the prose equivalent of watching women romp on stage to AR Rahman’s music after years of earnest and well-meaning “open-the-sindoor-box” recitals. The contemporary landscape and language of the stories might make you want to label them “millennial”, but that’s saying little. What they do is exhibit a generous and refreshing curiosity about the experiments of life and love in the cities of post-liberalisation India.

The Women Who Forgot to Invent Facebook and Other Stories

The Women Who Forgot to Invent Facebook and Other Stories

Naturally, the internet (about 25 years old in India) is what threads the book together; deceits and diversions play out over email and Orkut chatrooms, Twitter timelines, dating sites and meditation apps. The stories are concerned more about people, says Susan, 41, than “with tech in the way of speculative fiction”.

One of the first stories she wrote in this vein was about a “highly online life of a nerdy bibliophile” around 2007, which Susan did not include in the book. “My life was highly online for a long while and so to write about it became a fun thing to do,” she says. The early days of the internet are a vivid memory for the Bengaluru-based journalist-writer. “I was 19 years old and, like the characters in ‘Trinity’, I had gone to a festival and then I found there was the option of keeping in touch with others over email. So I walked five minutes from my house to a cyber cafe and made an email id,” she recalls. Two decades ago, in Indiranagar, where Susan lived, “every second or third building was a cybercafe… which were oddly public and private spaces”. “Even the small shops that sold bananas and newspapers had two computers. It was super accessible and quite amazing. I remember the first search engine, the option of using multiple tabs…whoa! You could do suddenly do two things at the time,” she says over a video call.

Like a true digital native, The Women Who Forgot… conveys the sense of discovery and deceit that the internet enables. There is a multiplicity of registers in the stories, packing in pop culture references from Hindi and Malayalam cinema and Indian internet without painstaking explications. Characters burst in and out of bars, chatrooms, offices and literary festivals; parents, with the exception of the mother-daughter in ‘Missed Call’ are shadowy presences, mostly redundant in a world of the young.

The language of the book is playful and unserious; pushing Indian English to embrace the many unofficial accents and voices in the auditory landscape of its cities. “I am very good at picking up some elements of a language, though I never achieve a high degree of competence. So, it is natural for me to write like that. It is also a part of living in Bengaluru, where people switch in and out of languages without thinking,” says Susan.

The conversational element of the stories comes from Susan’s being “a compulsive teller of anecdotes.” “It is not something special about me. Most Indians are compulsive storytellers, they will chew your ears off if you give them a chance. A lot of my effort in writing is to retain all our natural gift for storytelling, and capture our specific experiences in our stories,” says Susan.

The women in the book are its highlight, but Susan appears to be drawn to the conflicts between women as much as the possibility of friendship. “Women who are my peers or significantly older have been crucial to shaping my life. They have brought me up and sent me out to a world much more than my family. But it is not a Pollyannaish relationship. It has been very complicated, with lots of tension and big fights. This is a very straight person’s perspective. But I feel men don’t matter, except in a certain sexual or romantic context. Women have dominated my life in ways that boyfriends never did. They didn’t take my life and tear it apart from the way women did or put it back together as women did,” she says.