Heera Devi with Agnivesh. A loan of Rs 20 kept her toiling at a quarry for years. (Express photo)

Heera Devi with Agnivesh. A loan of Rs 20 kept her toiling at a quarry for years. (Express photo)In 1980, Heera Devi took a loan of Rs 20 from a contractor at a stone quarry in Haryana where she worked, to send to her two young sons back at their village in Madhya Pradesh. Devi would spend years toiling at the quarry trying to repay the loan and the interest the contractor demanded.

“No matter how much she worked and how little she was paid, the contractor would always say she was yet to repay the full amount. It was only when Swami Agnivesh started fighting for bonded labourers did she even understand she was being exploited. He made a union, held meetings, opened schools, taught the workers their rights, and then fought this legally,” says her son Mayaram, now 55.

Among those present at the funeral of Agnivesh, who died in Delhi on Friday, was a teary-eyed Totaram, as grateful to the Arya Samaj leader and the anti-bonded labour crusader for coming to his father’s help. Now 49 and a Delhi government employee, Totaram says his father, uncles and cousins were rescued from a stone quarry in the Aravallis in Haryana in 1984 by the Bandhua Mazdoor Morcha (BMM) founded by Agnivesh.

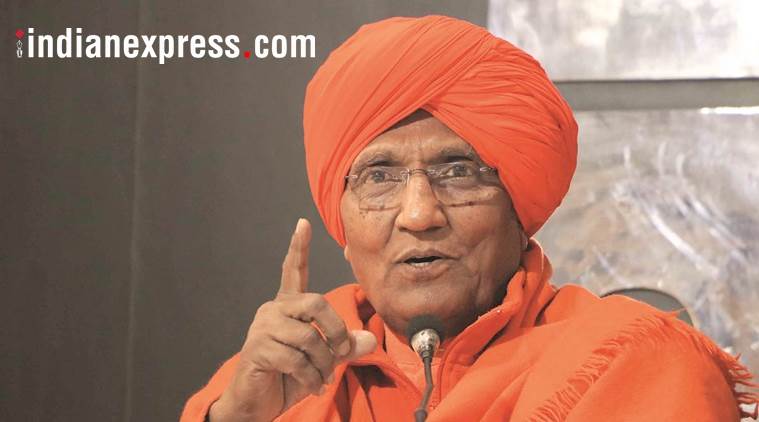

Swami Agnivesh (Express Photo by Kamleshwar Singh)

Swami Agnivesh (Express Photo by Kamleshwar Singh)

“People from our Bhil community used to work at the quarries for Rs 5 per day. Ghar nahin chalte paanch rupaye se (One can’t survive on Rs 5). Swamiji opened a school in the basti for the children, and I attended it. He would give speeches on workers’ rights… I used to be mesmerised. He freed my brother-in-law too and helped rehabilitate his family in Alwar,” said Totaram, as he lingered after the last rites were over.

Many of the people the BMM freed — from quarries, brick kilns and carpet-weaving units, several of them children at the time — were present at the funeral, held in Gurgaon on Saturday.

Bhagwan Singh recalled that before Agnivesh opened a school near the stone quarry in the Aravallis, he too would work there for Rs 2 a day, at the age of 15. “My family had taken a tiny loan from a contractor even before I was born… We didn’t see anything wrong with it, and then Swamiji taught us about our rights,” said Singh.

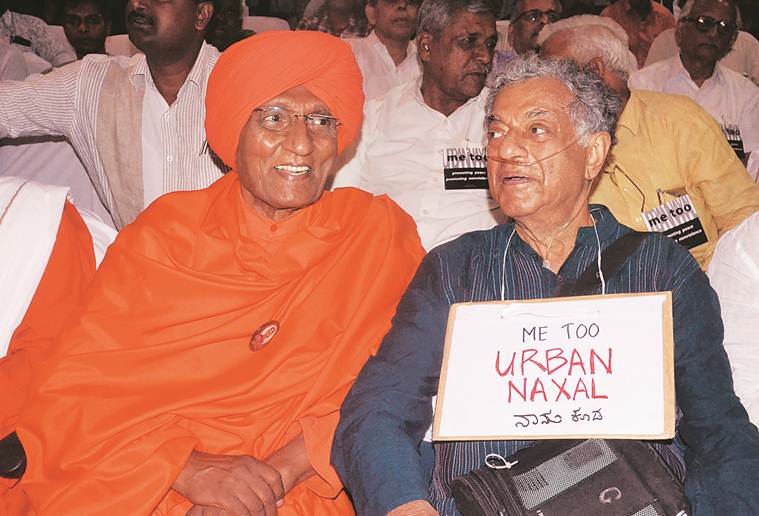

Actor and playwright Girish Karnad with activist Swami Agnivesh at an event to mark the first anniversary of journalist Gauri Lankesh’s murder, in Bengaluru. (Photo: Kashif Masood)

Actor and playwright Girish Karnad with activist Swami Agnivesh at an event to mark the first anniversary of journalist Gauri Lankesh’s murder, in Bengaluru. (Photo: Kashif Masood)

He would go on to study at the school, the first in his family, and then college. “If Swamiji hadn’t rescued us, we would have added several generations of uneducated, bonded labourers to our family,” Singh said, speaking over the phone.

Also present at the funeral was Palam-based Rehana Begum, who worked as a sanitation worker from 2014 to 2017, cleaning toilets at a park in Dwarka. “Whenever I demanded money, the contractor would say he would evict me from the slum I lived in. One day, I fell sick and a kind passerby took notice. Three days later, workers from the BMM visited me, and took the case to court. I was paid Rs 2 lakh as compensation and was relocated to Palam,” she said, adding that there was no way she would not have come to pay her last respects.

Ramesh Kumar Suryavanshi (45), who manages a canteen at a private company in Faridabad, said he too was forced to work at a quarry to repay a loan taken by his father decades ago, till Agnivesh taught them this was wrong. “I might have been a labourer today with no access to education… I feel like I have lost a family member,” said Suryavanshi.

With Anna Hazare (Express Archives)

With Anna Hazare (Express Archives)An old colleague of Agnivesh, Suman (60), recalled how an article in a magazine on labourers who had come to Delhi from all over India to build hotels and stadiums for the Asiad Games in 1982 took him to a small village in what is now Jharkhand. “We came across a group of women who told us how their children — all minors — were stuck at a carpet-weaving unit in Mirzapur. Not only did Swamiji help free the boys, he fought this case legally. He was gutted to know the torture the kids underwent — hung from a jackfruit tree and beaten up, not fed for days, and 14-hour work shifts. It was after this case that we started getting hundreds of rescue calls.”

Another colleague, Nirmal Gorana, the general secretary of the BMM, said Agnivesh would always say, “Speak to the worker.” Even when hospitalised, Agnivesh asked him for a 15-year plan for the BMM, Gorana said.

Bimla Devi, 62, paid Rs 1.5 per day at a quarry in the early ’80s, recalled how the BMM lit a fire, with meetings held in the dead of the night inside schools, inns and shanties of labourers, and how it spread. “The contractors didn’t want us to meet Swamiji, they would threaten us, even with violence. I was beaten up, but this was the first time someone was speaking about the exploitation we faced at the kaala pahaar (Aravallis),” said Devi, adding that “at least 150 family members” of hers were freed from the site by the BMM.

“My son works as a driver for an IIT-Delhi professor, not as a bonded labourer,” Devi added. “We owe this to Swamiji.”