The tinpot dictators of Mumbai

Many housing societies and neighbourhood associations in the city have taken undue advantage of the

Last month, after months of severe restrictions to curb the spread of Covid-19, as the city went into unlock mode, lawyer Shilpa Sharma’s society in Raheja Vihar, Chandivali decided to go their own way. They sealed two wings of the society with 170 families in it for 14 days straight. “The city had opened up, but we were not allowed to step out of our flat. We could only use the lift to pick up deliveries,” says Sharma. “From our balcony, we could see the rest of the city freely enjoying morning walks, even the neighbourhood kids had resumed their games. It felt absurd.”

When she questioned the building’s managing committee, she was told that they were merely following the BMC orders, which makes it mandatory to seal entire wings of complexes, if three or more Covidpositive cases are found. But a BMC doctor informed Sharma that it was, in fact, the managing committee that had requested that the wings be sealed as a precaution.

“When I protested, a committee member announced, on loudspeaker, that if we step out [of our apartments], criminal action would be initiated against us. I felt like a prisoner in my own home,” says Sharma.

What infuriates lyricist Pinky Poonawala of Versova is that society policies are currently being shaped by the whims and fancies of those in charge. No domestic workers and delivery personnel are allowed inside her building, even though residents can step out at will. “There’s no consideration for the many senior citizens who rely on the assistance of domestic help,” says Poonawala, who lives in Everest building. “For groceries and other supplies, the elderly had to depend on security guards, who venture outside the building to do their shopping. If that’s not deemed a health risk, why is it one to allow help in?”

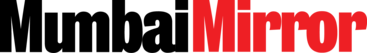

A Goregaon (W) building has a long list of restrictions, and residents who want to call their domestic workers are forced to submit a letter taking responsibility for any Covid cases that occur in the complex thereafter

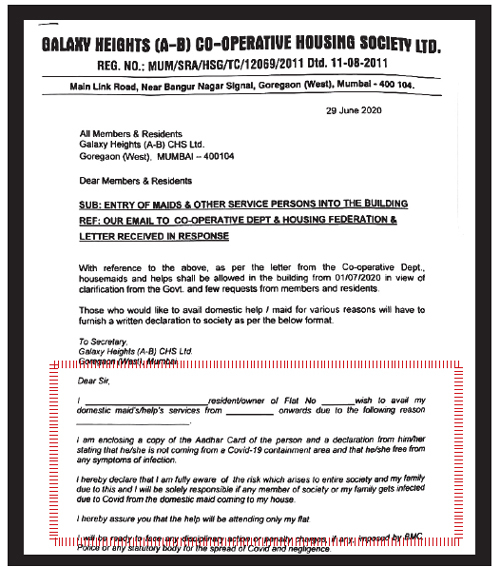

Similarly, residents of Navi Mumbai’s Newa Garden CHS (where domestic help was allowed in from September 1) can’t understand why the society was so strict about not allowing the help to enter when labourers could carry out renovations in apartments. Meanwhile, the managing committee of a Colaba building decreed that domestic help that don’t live inside the premises, must keep masks on all day, even while inside the apartments. Green rights activist Zoru Bhathena’s building, too, has imposed restrictions. “Initially, only live-in helpers were allowed [in my building], but now everyone is allowed, except the laundryman and the milk man. If the man fixing my internet is allowed to enter the building, why is the laundryman being kept out?”

We were not allowed to step out of our flats. A committee member announced, over loudspeaker, that if we step out, criminal action would be initiated against us. I was a prisoner in my own home

There is no doubt that the pandemic has made us an extremely paranoid lot. On Saturday, Mirror reported how 87-year-old Miradevi Sheth’s son had locked her in for months to prevent her from contracting the virus (while she fed some strays) and bringing it home. But these restrictions don’t stop at who can or can’t enter a building; they’ve gone beyond to stop people from feeding dogs and growing plants, and other such arbitrary things.

Lawyer Afroz Shah may be stating the obvious when he tells us that managing committees have been overstepping their boundaries for a while now. But, according to Ramesh Prabhu, founding chairman of the Maharashtra Societies Welfare Association, no one knows what those boundaries really are. And the absence of guidelines has only emboldened the bullies.

Time for power play

Take, for example, Daisy D’Souza, a 58-year-old tutor, who lives in Deep Tara CHS in Andheri (E). D’Souza is not yet allowed to conduct her private tuition classes at home, even though guests of other residents can enter the building. This, despite the fact that her ground floor apartment has a separate entrance and her students can avoid accessing the building’s common areas. D’Souza says, “Whatever we do, the secretary [of the housing society] and her husband have a problem with it. When I started growing plants in August, they called the BMC, saying they were being troubled by mosquitoes. The BMC found nothing in the pots. They have just gone power mad.”

Daisy D’Souza is not allowed to tutor students at her Andheri home even though visitors are allowed in the building; PIC: NILESH WAIRKAR

Several residents of Gardenia Housing Society, part of a Kandivali complex called Valley of Flowers, believe that the chairman and secretary of their building have “turned into dictators”. A vendor, who had come all the way from the Konkan to supply mangoes to some flats, was turned away “as the building secretary said we should have sought his permission first — even though fruits are essential items,” a resident says. Another resident adds that while visitors and domestic help were not allowed to enter until a few days ago, the chairman’s wife managed to get her beautician to visit her apartment. “When people complained, we received an email from the managing committee saying beauticians are allowed, but domestic workers are not,” says a frustrated resident.

The fault in your staff

Gardenia’s secretary, Surjeet Chatterjee, tells Mirror that beauticians from only one company were allowed in as “they follow all safety protocols”. The managing committee later sent out an email to residents saying domestic workers would be allowed in, provided residents sign an undertaking accepting responsibility for any Covid-19 cases that may occur in the building thereafter.

A sign lays down the law at a Navi Mumbai complex where rules are being enforced selectively

Isn’t it absurd?” a resident asks. “It’s not like the residents are not stepping out. Many are going to work now. And we know that people can be asymptomatic. Is it possible to gauge who brought the virus in?”

Abhijit Dhiwar, 44, a resident of

Rifts and tantrums

Yatindra Pal, Tarapore Garden’s secretary, says that the indemnity letter is meant to serve as a deterrent, and that it has indeed done the trick. “Only about 20 per cent of apartments have asked their staff to return to work,” Pal says, adding that the pandemic has left committee members torn between relaxing the rules and continuing to keep utmost precautions in place. “It’s not possible to please everyone. But we have 290 out of the 294 families on our side, so I think we’re doing well,” he says, adding that it’s no

Animal lovers have also been at the receiving end of lockdown rage. There’s always been friction between those who feed animals and those who fear them, but unconfirmed rumours about animals being carriers of the virus have heightened tensions between these two groups. Last month, feeders living around Napean Sea Road were stunned to see a notice outside Priyadarshini Park saying they were no longer allowed to feed stray animals inside the park because of Covid-19-related restrictions. The park, they say, has been home to more than 15 dogs and 30 cats for decades now. After a huge tussle with the Malabar Hill Citizens’ Forum, which maintains the public space, the animals were finally taken out of the park and the feeders are now looking after them.

“The animals had been starving for days because we were not allowed to enter the premises,” says local resident Commander (retd) Raj Saini. Activist from People for Animals Lata Parmar got BJP MP

Amit Pathak, who runs

Abhijit Dhiwar’s building in Goregaon wants people to take responsibility for future Covid cases, if they let domestic workers in; Pinky Poonawala’s (right inset)building society wouldn’t allow domestic workers in, but residents could come and go at will

Her building’s secretary Jayesh Parelkar, however, denies this, maintaining that the building has adequate housekeeping staff to attend to such issues. He tells Mirror that Chanda has never approached the committee regarding any such incident. “If there are tensions between individuals, I can’t comment on that,” Parelkar says.

Pathak, however, says experiences like hers are painfully common. “Neighbours have been ganging up on those who feed animals,” he says, sharing the account of a woman in Goregaon (E) who was similarly harassed for feeding strays that lived on her street. “Even pet owners have had a hard time,” Pathak adds. Two sisters, both senior citizens, living in Chembur, had no choice but to give their cocker spaniel and indie up for adoption around mid-July.

“First, there was a problem with an elevator, and since they couldn’t bring in repairmen at the time, we were told we can’t use the other elevator for pets,” shares the older of the two women. “Then, they started crossing off areas like the garden, the parking area and so on, saying pets can’t be walked here or they can’t be walked there. My sister and I waited patiently at first, but we finally gave up as it seems this situation will persist for some time.” Giving up the dogs that had been their only family for some six years was absolutely heart-breaking, says the younger sister, “but there was no other way,” she says, sharing that the adoptive parent has assured them that they can visit regularly once life returns to normal. “We’re not sure when that will be.” Their building still has a number of restrictions in place.

Write those wrongs

Pathak says the only thing to do in cases like this is to ask the building to put these rules down in writing. “Then they can be challenged,” he says, pointing out that there have been rulings by the consumer forum and various courts to support the rights of animals and pet owners.

The Malabar Hill Citizens’ Forum refused to allow animal feeders inside Priyadarshini Park, citing new Covid-regulations

A noted film photographer, who lives in

But the problem is that the septuagenarian sisters would rather not take their complaint to the authorities, especially not at a time like this when they have been told that their age makes them particularly vulnerable. “These society ‘dictators’ count on people’s reluctance to escalate the matter,” says Prabhu.

No shortcuts

It doesn’t help that in June the Bombay High Court declined to hear a public interest litigation filed by advocate Yusuf Iqbal Yusuf on behalf of residents of various housing societies who complained of unreasonable restrictions being imposed by managing committee members. At the time, Advocate General Ashutosh Kumbhakoni stated that barring instances where the law has been violated, the state does not interfere with the functioning of housing societies. He said such disputes could be taken up before the cooperative court instead.

Everyone is allowed [in my building], except the laundry man and the milkman. If the man fixing my internet is allowed to enter, why is the laundryman being kept out?

“Consider what that entails,” says Prabhu. “First, you take your problem to the registrar’s office or send an email. The registrar may decide that the society is wrong and issue directions, which would take 15 days or so. Then, in spite of that, if the society does not budge, you can take the matter to the cooperative court. Battling it out there could take six months to a year… But you need this matter settled now, not a year later,” says Prabhu, adding that the chaos could be cleared if the collector or BMC would simply say that the guidelines, which were issued some months ago, are no longer valid. In May, when the lockdown was eased in New Delhi, for example, the Delhi government issued an order restricting the role of such bodies in response to a flurry of complaints about essential workers being barred from buildings, and so on, despite a relaxation of restrictions. However, so far, no government body in Maharashtra has issued such instructions. “No authority wants to do so, because, if [Covid] cases spike subsequently, they don’t want to be held accountable,” he says.

Animal rights activist Madhu Chanda says neighbours assaulted her husband to get them to stop feeding strays

In the absence of such a missive, residents must fight their own battles. In July, teacher Manisha Bhatnagar acted against her building society and lodged a complaint with the deputy registrar, saying her building was not allowing domestic workers inside. Directions were issued to the building’s managing committee on July 1 and subsequently on July 29, and the committee then revised the rules to allow the help in. Additionally, deputy commissioner of police N Ambika says that residents can count on the cops’ support if their building committees refuse to allow workers in. “You should file a complaint with the police,” she says. Prabhu is stunned that it’s come to this. “It’s like there’s no humanity left in the city. If you ask me whether societies have the right to do all this, the answer is no,” he says. “These rules are ridiculous.”

—With inputs from Anjana Vaswani, Satish Nandgaonkar, Payal Gwalani, Arnab Ganguly, Sharmeen Hakim and Linah Baliga