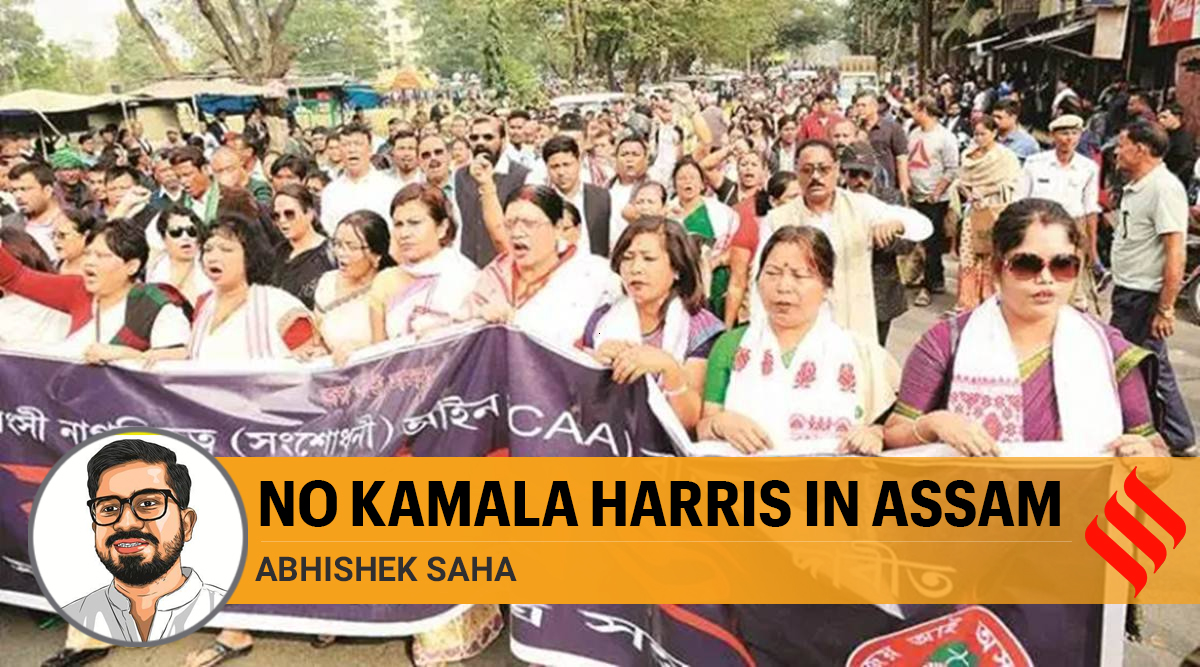

The state government had emphasised on the speedy implementation of provisions of Clause 6 of the Accord as an antidote to the Assamese opposition to the CAA. (Express file photo)

The state government had emphasised on the speedy implementation of provisions of Clause 6 of the Accord as an antidote to the Assamese opposition to the CAA. (Express file photo)The story of Kamala Harris, a woman of Indian and Jamaican origin running for Vice President in the US presidential elections, is inspirational as well as cathartic for migrants and their descendants across the world. It is ironic that at a time when there is jubilation in India on her nomination, in Assam, a report of a Union Ministry of Home Affairs-appointed high-level committee suggests mechanisms to stifle the rights of large sections of migrant-origin people.

In 1958, Harris’s mother Shyamala — later a well-known breast cancer researcher — migrated from India to study at UC Berkeley. She was 19. She met a Jamaican economics student Donald Harris, who had migrated to the US in 1961 and later taught economics at Stanford. They got married in 1963. Harris was born a year later, an American citizen by birth.

The day when Harris was chosen as the running mate of Democratic nominee Joe Biden, I was writing a news report on the recommendations by the Committee on Implementation of Clause 6 of the Assam Accord. This clause provides “constitutional, legislative and administrative safeguards” for “Assamese people”.

The 14-member committee was headed by a retired Gauhati High Court judge and included influential Assamese advocates, academics and student leaders. Their report recommends that “Assamese people” be defined using 1951 as a cut-off — those who were residing in Assam before January 1, 1951 will be defined as “Assamese”. It then suggests a slew of reservations for “Assamese people”, including 80-100 per cent of Assam’s seats in Parliament and the same proportion in assembly and local bodies (inclusive of pre-existing reservations). It recommends job reservations of up to 80-100 per cent in government and private sectors and asks that “land rights be confined” to the “Assamese people”. It also recommends an Inner Line Permit regime in Assam, which could prove a hindrance for investments and tourism.

The Assam Accord, signed in 1985 after a long “anti-foreigner” movement, set a cut-off of midnight of March 24, 1971 for the detection of non-citizens in Assam. The Assam NRC uses pre-1971 lineage to establish Indian citizenship — and those who fail to do so first, in the NRC and then, in the foreigners’ tribunals, stand the risk of being put into detention camps. After an exhaustive NRC exercise, costing over Rs 1,600 crore, using 1971 as a cut-off year, there now emerges a further exclusivist idea to ascertain who is an “Assamese” based on pre-1951 lineage in the state.

Assamese groups have long stressed that since Assam has “accepted” migrants from 1951 to 1971 as per the Accord, implementation of Clause 6 of the pact is necessary to safeguard the interests of the state’s indigenous people. The state government had emphasised on the speedy implementation of provisions of Clause 6 of the Accord as an antidote to the Assamese opposition to the CAA.

But at the same time, the recommendations of the high-level committee have suggest a framework that could end up rendering a large section of Assam’s society as an inferior class of citizens. This exclusion will comprise both Muslim economic migrants of Bengali-descent as well as post-Partition Hindu Bengali refugees, who can prove that they or their ancestors were residing in Assam between 1951 and 1971, but not before that. They might be stripped of several rights and privileges. They will be Indian citizens as per the 1971 cut-off but may not be represented by a legislator or may be ineligible for a job or may not be able to purchase land.

A 2019 Washington Post report noted that in her first campaign stop after announcing her presidential bid, Harris was asked by a reporter how she would describe herself since she was both “African American” and “Indian American”. Harris replied that she was a “proud American”.

Harris’s parents had migrated to the US in the 1950s and 60s seeking education and better opportunities. Today, their daughter is running for one of the top offices in the country. In Assam, in contrast, proposals are being drafted to deprive Indian citizens, who or their ancestors migrated in that era, from rights rightfully available to any ordinary citizen. Harris, if hypothetically asked to trace her ancestry in the US, could possibly be able to fetch records not prior to 1958. But in Assam, a document from 1958, might not be good enough to ensure one’s candidature for election or a job at a state or private sector outfit — if the recommendations of the high-level committee are implemented.

At a time when the world battles growing concerns of statelessness, can India afford to have a community of second-class citizens in a state strategically important like Assam? As the 2021 Assam elections draw closer, all eyes will be on the BJP governments at the Centre and the state as to how they respond to the recommendations.

abhishek.saha@expressindia.com