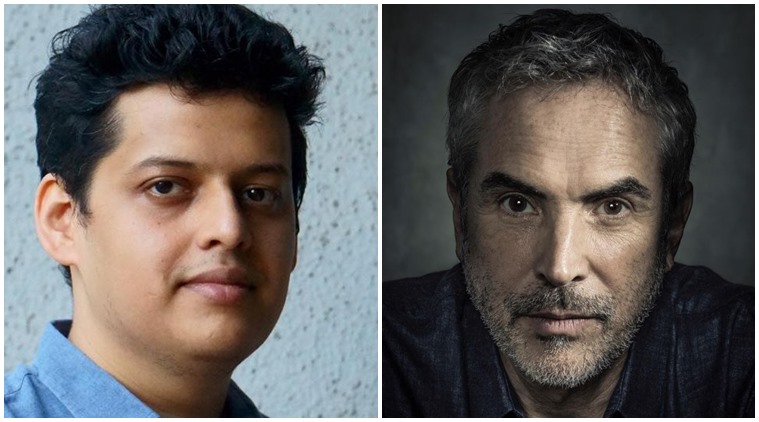

Chaitanya Tamhane opens up about his relationship with filmmaker-mentor Alfonso Cuaron. (Photo: PR Handout)

Chaitanya Tamhane opens up about his relationship with filmmaker-mentor Alfonso Cuaron. (Photo: PR Handout)

At the age of 17, Chaitanya Tamhane was building a DVD library at home using money earned from writing Balaji television soaps. 16 years later, the director is gearing up to compete at the Venice Film Festival with The Disciple, which has been executive produced by Oscar-winner Alfonso Cuaron.

In an interview with indianexpress.com, Chaitanya talks about his journey from the Balaji office to his National Award-winning Court to The Disciple, being mentored by Alfonso Cuaron and the one man who helped him stay away from the trap of mainstream cinema.

Here are excerpts from the conversation:

Q. You went through your share of struggles to make Court. Did its success make the journey of The Disciple easier?

That’s a very interesting question. Yes, in some ways it was easier because the success of Court led me to Alfonso Cuaron as I was invited to apply for the internship programme (Rolex Arts Initiative), and certain people were excited to be a part of The Disciple because they liked Court. But on the financial side, it was still Vivek (Gomber). A lot of people said it was going to be easier for me to get international funding or investors, but none of that happened, which is revealing in a way.

That makes me wonder whether my struggles are going to get back to zero the day Vivek runs out of money. Hopefully, that will never happen (laughs). But the point is there’s just one guy who has that kind of undying faith in me and my work even though he knows this is not the most commercial project.

Around the world, arthouse films are produced using institutional funds or co-production with many other countries. We don’t have any of that. It’s just one person’s money. It’s revealing in a way, no?

Q. Yeah. Independent directors often say that they get a lot of calls making big promises, but when it really comes down to making films, the calls are never answered.

I got around four-five offers from major production houses, saying they would want to produce my next film except that none of them had seen Court. They approached me based on the press that they had read and the awards that I had got. I was like, “Why don’t you first watch the film?” It’s funny sometimes.

Q. In my understanding, you knowingly indulge in complexities. You knew nothing about Indian classical music when you fell in love with it and decided to tell its story on screen with The Disciple. You prefer taking long takes, relying less on editing. Your audition process is exhaustive – you wanted Marathi speaking musicians for your cast in The Disciple, and so on. Does this come naturally to you?

(Laughs) You have touched upon a few specifics, and there are different answers for each one of them. For me, it’s the need of the narrative. For example, we auditioned actors, but we found it would be near impossible for them to fake knowing music for this long because of my wanting to do long, uninterrupted takes. If they focus on memorising musical phrases, then their acting will go for a toss. We thought practically it would be little bit easier to get musicians to act.

Yes, it is a very detail-oriented process because you want to create the atmosphere and authenticity in the best possible manner. So, we not only cast musicians but we got actual concertgoers and music lovers for background characters.

We had to audition that many people because the pool was narrow. It had to be somebody Marathi speaking, a Khayal music practitioner. They have to physically fit the character demand. They have to be interested and should have an acting vein in their body so that they can deliver scripted lines and not be nervous in front of the camera. So that was challenging.

With editing, it’s not that I don’t like it. The editing pattern of this film was very different from that of Court, but then that’s according to the demand of the story. But it’s true I generally like uninterrupted takes, wide shots.

Q. What about venturing into the unknown? Like with The Disciple.

I find my own life very boring, insular and normal. I get bored very easily. So for me, it’s a great opportunity to educate myself, to reflect and seep into this other world that I am discovering. So, it becomes like the marriage of the outside and the inside.

For example, The Disciple is about the journey of a classical musician, but I don’t think what’s happening to cinema as an art form in the 21st century is very different to what’s happening to music. It’s very personal to my journey as a filmmaker. Cinema is also not relevant in the same way that it was in the 20th century. Neither is the patronage nor the way people are consuming it. So, I am exploring both similarities and differences between these two worlds.

The world of classical music is intoxicating. It’s so rich in all its complexities, stories and contradictions that I didn’t have to do much to fall in love with it.

The Disciple is described as a “journey of devotion, passion, and searching for the absolute in contemporary Mumbai.” (Photo: PR Handout)

The Disciple is described as a “journey of devotion, passion, and searching for the absolute in contemporary Mumbai.” (Photo: PR Handout)

Q. How would you describe The Disciple?

It is a journey of an Indian classical vocalist who has been raised by his father and inculcated into this music. He has grown up on these stories of masters of the past, the secret knowledge and the intimidating, complex art form that they are trying to perfect. The kind of values that vocalists grow up on. But he is also trying to navigate a practical, real life.

It’s similar to what you are talking about independent filmmakers in contemporary Mumbai. So The Disciple explores those questions of what is pure and what is this music and its place and its journey because there is a theoretical and a practical side.

Q. What was it like having Alfonso Cuaron being involved with The Disciple since the beginning?

It was like having a master or an expert who is so generous with his feedback. I, of course, consider him one of my gurus but he is also like a very dear friend. He does not have that mentor-like vibe. He is chill, very calm and friendly. We are bantering most of the times. But when it comes to cinema, he is very serious and opinionated.

But there was never any interference or dictating what I should do. It was always feedback and opinion. When it comes to somebody of his stature, even a 45 or a 30-minute conversation can give you so much to learn from and open your mind that you start thinking in a different way. He helped me with the edit. He worked with me on the script, and he continues to help me with this whole thing.

Q. What’s been the most glaring change you have felt within since your association with Cuaron?

Alfonso pushes me to be fearless. For an independent filmmaker, in your mind, the restrictions come first. You limit yourself mentally, thinking, ‘We don’t have the budget. How will this happen? How will that happen?’ He pushed me to put the vision first ahead of all the problems.

He tells me to ask for the sky, aim for it, be fearless and then think about the rest. He says if the vision is there, the rest will follow. That has been the biggest change for me. Of course, there are many other things on a practical and a technical level when it comes to filmmaking.

On an approach level, this is it. This is again an ongoing process because I am a bit of a coward, an introvert in that sense. He is always pushing me to be more brave. I am not like that in filmmaking, but when it comes to life, I am more pessimistic.

Q. You have closely observed his work, his understanding of the craft. Does that give way to obvious influences in one’s work, when one has an intimate experience with a directing great?

Oh, yeah, absolutely! It’s like two filmmakers talking except that one has made seven or eight more films and has more resources. So, he has seen more monsoons than I have. He is at a very different stage in his life. That doesn’t really meddle with your world view or personality that goes into making a film. If anything, he is an enabler in that sense. He only helped me realise and find my own voice rather than imposing his.

In fact, he was generous enough to say that when he saw Court, he found that the film that he was going to make – Roma – had a very similar language. So, he keeps insisting that it’s a two-way process and dialogue.

Q. How often do you disagree with each other?

Quite a lot. But that’s also because most of the times we are joking around, and we both have really strong opinions about things. He is always pulling my leg, and I am mostly disagreeing with his historically funny accusations regarding me and my bad taste.

Q. Is it easy to present a differing opinion in front of a renowned filmmaker who has also mentored you?

It’s not that kind of a relationship. It’s not a formal rapport. But of course, I am full of respect and gratitude for him. I never really cross that line because he is very busy, doing multiple things. But whenever we meet or talk, we pick up from where we left.

Q. How do you look back at your early years in the industry when you used to write television soaps?

I was naive, getting a lot of money, and also the financial situation in my house wasn’t that well. It was a lot of money for me. It’s very interesting that the money I made from TV, I used in building a DVD library at home. That’s how I watched a lot of world cinema. I met a lot of my mentors in that Balaji office.

Those were people who had come from NSD and were world cinema fans. They suggested so many films to watch. That’s the last place where you would expect cinephiles and world cinema lovers.

Of course, one has bad experiences, but all that helps you. All the mistakes you make, all the bad things you see other people doing, you tell yourself you wouldn’t do that and that’s not the person you would want to be. So, I learnt lessons. I don’t have any regrets.

Q. So, what’s one such thing you are sure you would never do as a filmmaker?

I worked in theatre, made a short film, participated in inter-collegiate theatre competitions. All of that taught me the importance of the energy and the vibe you surround yourself with. How to manage egos, how to lead the team and how to be respectful and grateful for the work that others are putting in to realise your vision. So, all these things make you a director.

Q. I saw you share in an interview that at one point in time, you were on the verge of giving up your life. Almost 10 years later, you are gearing up for competing at the Venice Film Festival. That’s a huge journey. Do you recall the moment when you decided to take the leap of faith and rebuild yourself?

Honestly, it wasn’t me. It was Vivek Gomber who took that leap of faith. It was him who gave me the courage and the support – both in spirit and finance – to do what I wanted to do. It took me a year-and-a-half to write the script of Court, but not once did he try to rush me or question me. He was like, ‘Don’t worry about it.’ There was no commitment of him owning the rights to the script or that he would make the film or act in it. There was no such condition.

Once he read the script, he asked me for a couple of months because he said, ‘I want to realise this film.’ Then he came back after a couple of months and said let’s make this. I was 24 and a half then. That’s how that film was made. Even with The Disciple, it’s just him.

I feel very lucky to have somebody like Vivek because it’s not conditional on any festival selection or awards. He has always been very pure and honest to the process. For him, the process comes first, and the result is almost irrelevant. That’s why when someone compliments me saying, ‘Oh, it’s commendable you’re doing your own work and not falling for the traps of the mainstream industry,’ I always say that it’s because of Vivek who has enabled me to be this way and follow my voice.