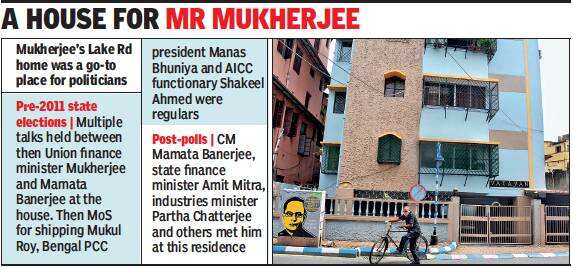

KOLKATA: The four-storey house in Dhakuria, near the Buddha Mandir, fell silent. Even the few cars on the road slowed down a little to take a better look at the two second-floor flats of Pranab Mukherjee.

For over two decades, the house has been much more than a mere address in south Kolkata. It was witness to the changes in Bengal politics as Trinamool—as a breakaway from the Congress and along with the Congress—emerged as the first serious challenge to the Left. The house watched on as the Left Front’s three-decade-old government began to crumble in 2009 and finally fell in 2011.

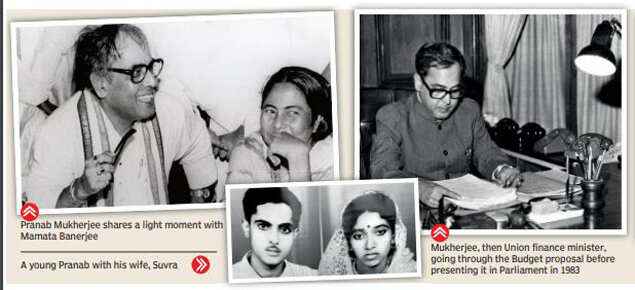

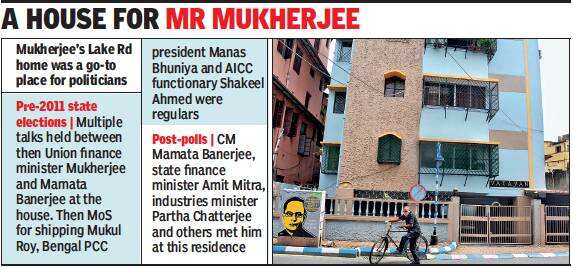

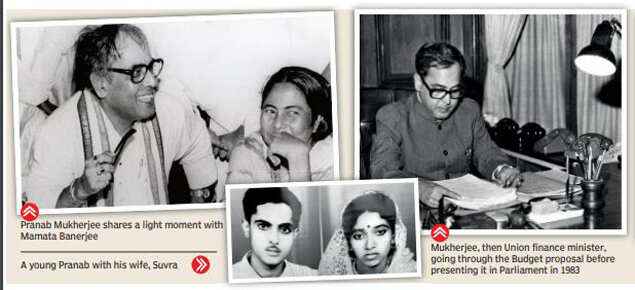

Political journalists, photographers and Congress and Trinamool supporters, who would gather outside the house, still recall the long wait even as editors and senior leaders kept calling up for updates. “The telebhaja shop next to the house was our recourse. We learnt from our experience a big political announcement was about to be made when a stool would be placed near the main door,” said a journalist. Many felt the political roadmap for Bengal would be laid at the late-night meetings between Mukherjee and Mamata Banerjee. “Whether it was the 2001 assembly ‘mahajot’ or the 2009 and 2011 poll tie-ups between Congress and Trinamool —some in Congress were unhappy with seat distribution —it was Pranab babu’s astute statesmanship that helped soothe nerves and steer the coalition to wins. Almost all the meetings were held at this house. It’s no surprise Banerjee, as the chief minister, met Pranab babu there to discuss the state’s financial challenges,” said a political commentator.

Even as the President, Pranab babu, as he was fondly called in his para, never missed a chance to visit his home. “Whenever the road near the Buddha Mandir was abound with cops, we knew he would come. He had a standing instruction: not to stop Lake visitors from walking by even if it was time for him to step out. I had bumped into Pranab babu twice in the past few years. I raised my hand for a namaskar and he always returned the gesture,” recalled Piyush Roy (80), a retired professor.

Mukherjee spent most of his time in Delhi but people here considered him the local guardian. He ostensibly knew the pulse of the neighbourhood, a mix of one-room dwellings and multi-storied buildings and a hospital. “Mukherjee was the absent guardian. He put up at this flat during his Kolkata visits for three decades. He forged his bond in different ways—by sponsoring Shani puja at a local club to ensuring proper walkways for walkers,” said another local, Asish Jana. “The day he arrived here after assuming the President’s office will always be a special one,” said Aparna Guin, a neighbour.

Mukherjee’s humility made the neighbours feel he was one of them. He spent some of the Puja days there and his love for mochar chop did not go unnoticed. The house was close to his heart, said an aide. “Every time he visited, he met his relatives despite his busy schedule. It was here he loved receiving new books from acquaintances,” said a retired police officer who served in his security team.

For over two decades, the house has been much more than a mere address in south Kolkata. It was witness to the changes in Bengal politics as Trinamool—as a breakaway from the Congress and along with the Congress—emerged as the first serious challenge to the Left. The house watched on as the Left Front’s three-decade-old government began to crumble in 2009 and finally fell in 2011.

Political journalists, photographers and Congress and Trinamool supporters, who would gather outside the house, still recall the long wait even as editors and senior leaders kept calling up for updates. “The telebhaja shop next to the house was our recourse. We learnt from our experience a big political announcement was about to be made when a stool would be placed near the main door,” said a journalist. Many felt the political roadmap for Bengal would be laid at the late-night meetings between Mukherjee and Mamata Banerjee. “Whether it was the 2001 assembly ‘mahajot’ or the 2009 and 2011 poll tie-ups between Congress and Trinamool —some in Congress were unhappy with seat distribution —it was Pranab babu’s astute statesmanship that helped soothe nerves and steer the coalition to wins. Almost all the meetings were held at this house. It’s no surprise Banerjee, as the chief minister, met Pranab babu there to discuss the state’s financial challenges,” said a political commentator.

Even as the President, Pranab babu, as he was fondly called in his para, never missed a chance to visit his home. “Whenever the road near the Buddha Mandir was abound with cops, we knew he would come. He had a standing instruction: not to stop Lake visitors from walking by even if it was time for him to step out. I had bumped into Pranab babu twice in the past few years. I raised my hand for a namaskar and he always returned the gesture,” recalled Piyush Roy (80), a retired professor.

Mukherjee spent most of his time in Delhi but people here considered him the local guardian. He ostensibly knew the pulse of the neighbourhood, a mix of one-room dwellings and multi-storied buildings and a hospital. “Mukherjee was the absent guardian. He put up at this flat during his Kolkata visits for three decades. He forged his bond in different ways—by sponsoring Shani puja at a local club to ensuring proper walkways for walkers,” said another local, Asish Jana. “The day he arrived here after assuming the President’s office will always be a special one,” said Aparna Guin, a neighbour.

Mukherjee’s humility made the neighbours feel he was one of them. He spent some of the Puja days there and his love for mochar chop did not go unnoticed. The house was close to his heart, said an aide. “Every time he visited, he met his relatives despite his busy schedule. It was here he loved receiving new books from acquaintances,” said a retired police officer who served in his security team.

Coronavirus outbreak

Trending Topics

LATEST VIDEOS

City

Maharashtra: 3 cops dismissed from service in Palghar lynching case

Maharashtra: 3 cops dismissed from service in Palghar lynching case  Fresh India-China face-off in Ladakh: Srinagar-Leh highway closed for civilians

Fresh India-China face-off in Ladakh: Srinagar-Leh highway closed for civilians  SSR death probe: Dean of Cooper Hospital quizzed with regards to Rhea Chakraborty’s entry in mortuary

SSR death probe: Dean of Cooper Hospital quizzed with regards to Rhea Chakraborty’s entry in mortuary  Decline in medical condition of former President Pranab Mukherjee: Army hospital

Decline in medical condition of former President Pranab Mukherjee: Army hospital

More from TOI

Navbharat Times

Featured Today in Travel

Get the app