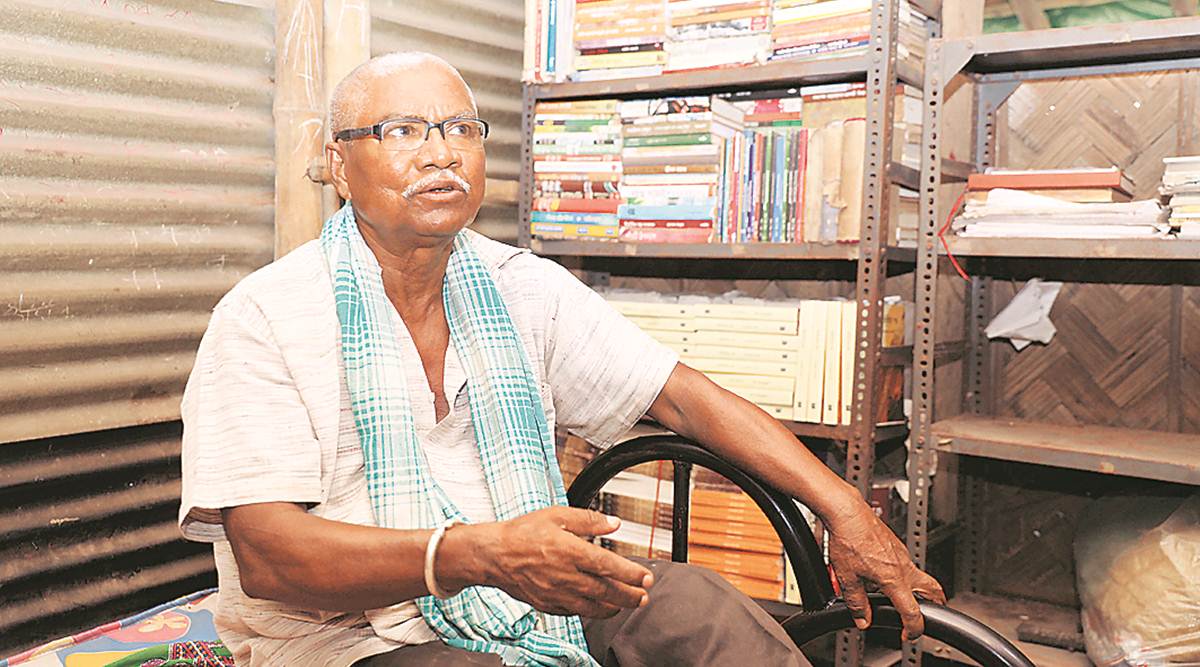

Byapari’s novels and short stories speak of the aspirations of and indignities suffered by those he calls ‘caste pariahs’. (File)

Byapari’s novels and short stories speak of the aspirations of and indignities suffered by those he calls ‘caste pariahs’. (File)In 2000, at a function at Hellen Keller Badhir Vidyalaya in West Bengal’s Mukundapur, one of the cooking staff had done an audacious thing — he had handed over a copy of his self-published novel, Boi Britter Shesh Porbo (The Last Chapter of the Book Episode), to the chief guest, Alapan Bandyopadhyay. “Unlike my colleagues, he did not consider it a breach of propriety by a lowly Dalit cook. He was very gracious and promised to read it,” says Manoranjan Byapari (70).

In the two decades since, Byapari went on to establish himself as a Bhasha writer of repute, whose Bengali novels and short stories speak of the aspirations of and indignities suffered by those he calls “caste pariahs”. But one thing remained unchanged — his status as a cook at the government school. Despite many requests for a transfer to a job that required less manual effort, Byapari continued to be employed as a group D staffer at the school, writing between shifts, and at night — the only time he says was his own.

On Wednesday, when the call came to inform Byapari that his petition had finally borne fruit and that he would be transferred to District Library, South 24 Parganas, near Amtala, it was only fitting that it was made by Bandyopadhyay, now West Bengal Home Secretary.

“In 2014, after I had had two knee replacement surgeries, it was difficult to stand and cook for more than 150 children twice a day, every day. The heat and physical effort was getting too much for me. Over the years, I had made numerous petitions to successive governments in person and through well-wishers and run around Bikash Bhavan (state government office in Kolkata) but nothing had worked out. So, my heart is full that this has finally happened,” says Byapari, who signed the transfer documents on Wednesday.

Byapari’s journey to literary stardom is a story of relentless struggle against odds. Born to parents who moved to West Bengal in 1953 from Barisal in what was then East Pakistan, he grew up on the margins of cosmopolitan life.

In 1975, when he was 20, and incarcerated in Kolkata’s Alipore Central Jail for petty violence, he learned to read and write from another undertrial. Two years later, after his release, when he started a new life as a rickshaw puller, a serendipitous meeting with writer and activist Mahashweta Devi set him off on a lifetime of writing.

Byapari’s Itibrittey Chandal Jibon (2012, Interrogating My Chandal Life: An Autobiography of a Dalit, translated by Sipra Mukherjee into English was published by Sage last year) went on to win several awards, as did many other works that followed. Over the last few years, several award-winning translations of his works have made him a familiar figure in the country’s literary circuit. His novel Batashe Baruder Gondho (2013, There’s Gunpowder in the Air, translated by Arunava Sinha into English was published by Eka in 2019) was shortlisted for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and JCB Prize for Literature last year.

In a long Facebook post on Wednesday, Byapari expressed his gratitude to his well-wishers, including Bengali theatre actor-director Shaoli Mitra, and an unnamed benefactor who helped convey his plight to Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee. In the post, Byapari wrote that he had always had faith in Banerjee’s benevolence. “I believed that if someone could tell her about my plight, my problem would immediately be sorted. If only she knew about my struggle and how I had fought to reach a place where I am known across the country, she would definitely help me out,” he wrote.

While he does not know the nature of his responsibilities yet or when he is required to join work, Byapari says he is happy to finally get a chance to be around books. In the meantime, he is nearly done writing his autobiography, Andhakar Ateet, Ajana Bhabhishyat (Dark Past, Uncertain Future). “Perhaps, after all the struggle, things will end on a happy note,” he says.