Good salaries, regular increments, rigorous entrance exams, professionally valued degrees for teachers, autonomy in curriculum development and student assessment are part of this reform process. However, the one remarkable feature which stands out is the implicit belief that teaching, caring and educating children is a highly demanding job and cannot be measured by quantitative measures alone. (File)

Good salaries, regular increments, rigorous entrance exams, professionally valued degrees for teachers, autonomy in curriculum development and student assessment are part of this reform process. However, the one remarkable feature which stands out is the implicit belief that teaching, caring and educating children is a highly demanding job and cannot be measured by quantitative measures alone. (File)School teachers, particularly in India, are caught in a strangely paradoxical situation — they are revered and ridiculed at the same time. The framing of teachers and perceptions around their work is rooted in mistrust. Hence, the rhetoric to closely supervise, monitor and hold them accountable has now become the norm rather than an exception.

The National Education Policy 2020 reiterates the importance of teachers and aspires for outstanding students (mentioned at least nine times in this section, without explaining what it really means) to choose the teaching profession. Several measures are suggested for the same including scholarships, housing, ensuring “decent and pleasant” conditions in school and providing opportunities for their continuous professional development (CPD). The measures are good and need to be carried out.

However, there are three key assumptions in this section which must be examined. One, outstanding candidates, if attracted to the teaching profession will enhance the quality of education. While one agrees with this assumption, one is not convinced with the measures suggested in the NEP to attract “outstanding” talent. They indicate minimal conditions for teachers to work and can hardly be seen as making any value addition to their professional lives. In fact, security of tenure and salary of a government school teacher is a definite attraction for most people, but in the neo-liberal regime, even that is under threat. So why would “outstanding” youngsters be interested in making this career choice? Linked to this is the oft-repeated idea of “passion” amongst teachers, as if passion alone will see teachers through and improve the quality of education.

Two, a comprehensive system of teacher assessment will lead to greater efficiency and accountability on the part of teachers. There is value in developing a system of assessment which will be used to reward some teachers and motivate others but would it be fair to assess (based on peer reviews, attendance, commitment, hours of service to CPD and other forms of service to the school and community ) all teachers by the same yardstick when they are working in starkly varying conditions? None of the parameters listed take cognisance of the backgrounds of children they teach. For example, students of teachers equipped with social and cultural capital will do well even with minimal inputs from the teachers, and vice versa. Moreover, to entirely discredit the experience gained by teachers which comes with years of service may not be appropriate.

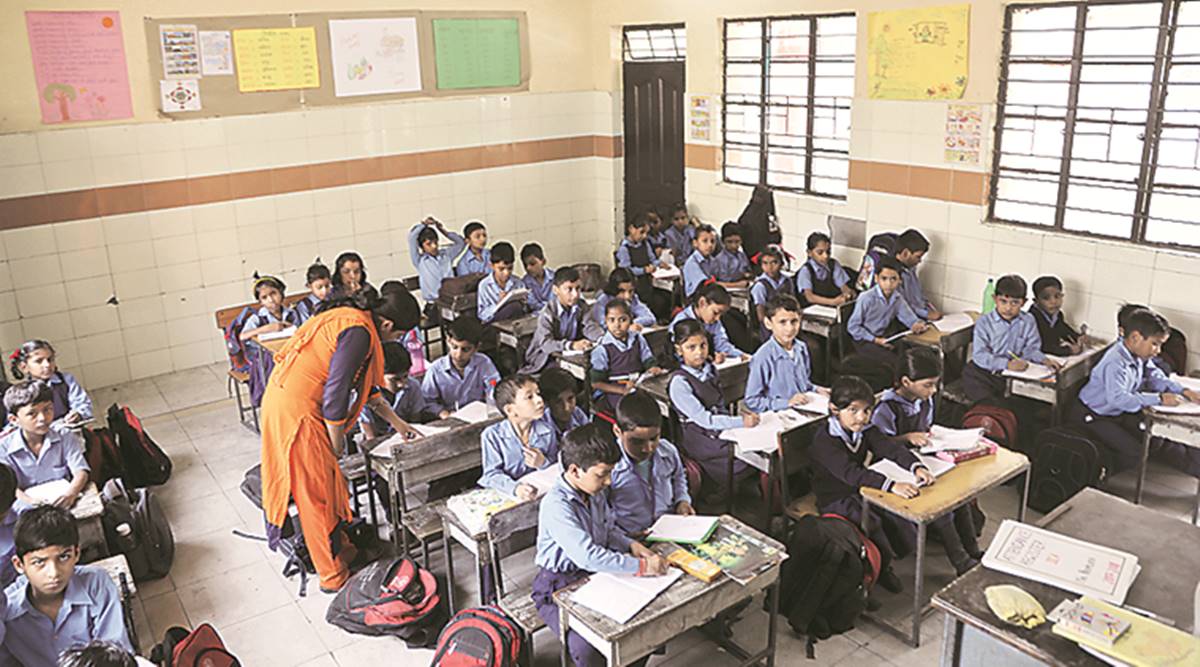

Three, good teacher education programmes would prepare good teachers. One can hardly contest this assumption, but the question is whether that alone will ensure effective teaching and meaningful learning in the classroom. For example, an outstanding teacher could crumble under pressure if her class has a huge number of students. Similarly, a teacher trained in a rigorous programme may also excessively depend on one textbook, if the externally designed student-assessment system is tightly tied to that book.

In the current context, there is increasing talk of connecting teacher accountability with externally tested learning outcomes of students, irrespective of the differences among them (that’s where government school teachers receive maximum flak), excessive monitoring through use of CCTV cameras, techniques such as deep breathing, meditation to calm their mind, and equating an enabling environment with personal attributes such as passion and motivation. In an environment, where cameras unabashedly chase them, records/documentation take precedence over teaching and the educational discourse is replete with voices which support the hiring of under-paid, contractual teachers who perform better than supposedly smug government schoolteachers, the morale of all teachers is low.

Despite variations in social contexts, if one were to understand how Finland, the world’s finest education system, transitioned from mediocre academic scores to outstanding results, one will find teachers at the centre of reforms. Good salaries, regular increments, rigorous entrance exams, professionally valued degrees for teachers, autonomy in curriculum development and student assessment are part of this reform process. However, the one remarkable feature which stands out is the implicit belief that teaching, caring and educating children is a highly demanding job and cannot be measured by quantitative measures alone. Therefore, even if students do badly, unwavering trust in teachers ensures that they are never in the radar of suspicion.

Implementing these ideas in our context may require a 360-degree change in mindsets, may confront several obstacles and take time, but that’s exactly what our education system requires. A turnaround of our attitude and policies towards teachers.

The writer is professor and dean, School of Education, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai