When Mitali Sathe stepped out of her home in Latur decked in a yellow sari, the mehendi on her hands and her green glass bangles gave her away. A member of an adolescent girls’ protection group had spotted the 15-year-old before her marriage to a man four decades her senior.

After her elder sister’s death, Mitali was the sacrificial bride on offer to the 50-year-old widower from Osmanabad: he needed her to care for the children. With their earnings as seasonal labourers cut off and no hope of seeing the daughter go back to school due to the pandemic, Mitali’s parents saw this as a way out. However, timely intervention of volunteers, cops and the District Child Protection Unit halted the wedding and led to the arrest of her suitor.

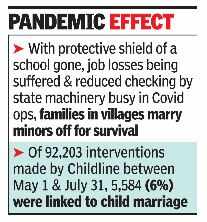

At least 92,203 interventions were made by Childline —nodal agency of the Union Ministry of Women and Child Development to protect children in distress — between May 1 and July 31. Of the total, 5,584 interventions (nearly 35 per cent) were related to child marriage.

In Mitali’s case, she was produced before the child welfare committee and counselled while her parents were made to sign a declaration that they would refrain from the illegal act of getting their underage daughter married. But Mitali’s escape from the scourge of “bal-vivah” or child marriage was an exception. During the pandemic, a large number of underage girls have been coerced straight from childhood into marriage.

With the protective shield of a school gone, job losses among daily wagers and reduced surveillance of district machinery currently focused on Covid-19 management, many families in rural areas are stealthily marrying their minor daughters off as a survival strategy — to reduce the number of children to support and the chance to make the affair less expensive and concealed.

“Many parents feel the lockdown is a good opportunity to get their daughters married at a lower cost. Instead of feeding over 200 guests and running up a debt of about Rs 2 lakh, they can get everything done for Rs 20,000,” says Sandhya Rani, 16, who heads the Savitribai Phule adolescent group in Latur where 16 child marriages have been reported between April and June alone compared to 19 cases over the previous nine months.

Another key driver has been the respite from heavy dowry. “Higher caste communities like Maratha, Yedam and Lingayat that would demand close to Rs 5 lakh from the bride’s family are ready to settle for Rs 1 lakh while dowry of Rs 1 lakh for daily wagers has come down to Rs 20,000. People need additional helping hands at home or to labour,” she explains.

“It feels like we’ve gone back 10 years in terms of progress that we had made,” rues Jayvant Jangapalle, coordinator for Kala Pandhari Magaswargiya and Adivasi Gramin Vikas Sanstha, a project partner of Child Rights and You (CRY) in the Latur and Nanded districts of Maharashtra. “After the launch of Integrated Child Protection Scheme in 2010, adolescent girl groups were activated which helped us monitor and nip child marriages in the area, members of the Village Child Protection Committee upheld basic rights and we were able to keep girls in school or in seasonal hostels to stem the practice of migrant parents taking along their daughters and marrying them off,” says Jangapalle.

Unfortunately the lockdown has upended girl group meetings or home visits that were therapeutic as much as empowering for the girls.

The approaching sugarcane harvesting season starting September when the banjara community migrates to districts across western Maharashtra for six months, activists fear, will render girls more vulnerable to early marriage. “Due to koyta padhati (sickle system) of hiring couples; parents prefer to marry off boys so that he and his bride can rake in an income which they can’t as a single cane cutter,” says Raju Sathe, a community organiser for CRY in Marathwada’s Parbhani district that has reported 16 cases between March and June as opposed to their past average of seven cases in a year.

With the criminality in child marriages yet to sink in, the pandemic has exposed the kind of work that still remains to be done. As a start, CRY along with NGO Vidhayak Bharti released a handbook last month on roles and responsibilities of Bal Sanrakshan Samitis and ways to tackle child protection at the community level.

After her elder sister’s death, Mitali was the sacrificial bride on offer to the 50-year-old widower from Osmanabad: he needed her to care for the children. With their earnings as seasonal labourers cut off and no hope of seeing the daughter go back to school due to the pandemic, Mitali’s parents saw this as a way out. However, timely intervention of volunteers, cops and the District Child Protection Unit halted the wedding and led to the arrest of her suitor.

At least 92,203 interventions were made by Childline —nodal agency of the Union Ministry of Women and Child Development to protect children in distress — between May 1 and July 31. Of the total, 5,584 interventions (nearly 35 per cent) were related to child marriage.

In Mitali’s case, she was produced before the child welfare committee and counselled while her parents were made to sign a declaration that they would refrain from the illegal act of getting their underage daughter married. But Mitali’s escape from the scourge of “bal-vivah” or child marriage was an exception. During the pandemic, a large number of underage girls have been coerced straight from childhood into marriage.

With the protective shield of a school gone, job losses among daily wagers and reduced surveillance of district machinery currently focused on Covid-19 management, many families in rural areas are stealthily marrying their minor daughters off as a survival strategy — to reduce the number of children to support and the chance to make the affair less expensive and concealed.

“Many parents feel the lockdown is a good opportunity to get their daughters married at a lower cost. Instead of feeding over 200 guests and running up a debt of about Rs 2 lakh, they can get everything done for Rs 20,000,” says Sandhya Rani, 16, who heads the Savitribai Phule adolescent group in Latur where 16 child marriages have been reported between April and June alone compared to 19 cases over the previous nine months.

Another key driver has been the respite from heavy dowry. “Higher caste communities like Maratha, Yedam and Lingayat that would demand close to Rs 5 lakh from the bride’s family are ready to settle for Rs 1 lakh while dowry of Rs 1 lakh for daily wagers has come down to Rs 20,000. People need additional helping hands at home or to labour,” she explains.

“It feels like we’ve gone back 10 years in terms of progress that we had made,” rues Jayvant Jangapalle, coordinator for Kala Pandhari Magaswargiya and Adivasi Gramin Vikas Sanstha, a project partner of Child Rights and You (CRY) in the Latur and Nanded districts of Maharashtra. “After the launch of Integrated Child Protection Scheme in 2010, adolescent girl groups were activated which helped us monitor and nip child marriages in the area, members of the Village Child Protection Committee upheld basic rights and we were able to keep girls in school or in seasonal hostels to stem the practice of migrant parents taking along their daughters and marrying them off,” says Jangapalle.

Unfortunately the lockdown has upended girl group meetings or home visits that were therapeutic as much as empowering for the girls.

The approaching sugarcane harvesting season starting September when the banjara community migrates to districts across western Maharashtra for six months, activists fear, will render girls more vulnerable to early marriage. “Due to koyta padhati (sickle system) of hiring couples; parents prefer to marry off boys so that he and his bride can rake in an income which they can’t as a single cane cutter,” says Raju Sathe, a community organiser for CRY in Marathwada’s Parbhani district that has reported 16 cases between March and June as opposed to their past average of seven cases in a year.

With the criminality in child marriages yet to sink in, the pandemic has exposed the kind of work that still remains to be done. As a start, CRY along with NGO Vidhayak Bharti released a handbook last month on roles and responsibilities of Bal Sanrakshan Samitis and ways to tackle child protection at the community level.

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Coronavirus outbreak

Trending Topics

LATEST VIDEOS

India

PM Narendra Modi mourns former cricketer Chetan Chauhan's death

PM Narendra Modi mourns former cricketer Chetan Chauhan's death  India sends 30 tonnes of technical equipment and material to Mauritius to help deal with oil spill

India sends 30 tonnes of technical equipment and material to Mauritius to help deal with oil spill  Sanjay Raut cites Russia to take jibe at Modi govt's 'aatmanirbhar' push

Sanjay Raut cites Russia to take jibe at Modi govt's 'aatmanirbhar' push  Caught on cam: Shops collapse in Dehradun due to continuous downpour

Caught on cam: Shops collapse in Dehradun due to continuous downpour  Study reveals most parents nervous to take their kids for vaccinations due to COVID-19

Study reveals most parents nervous to take their kids for vaccinations due to COVID-19  Vaishno Devi Yatra resumes

Vaishno Devi Yatra resumes

More from TOI

Navbharat Times

Featured Today in Travel

Quick Links

Coronavirus in MumbaiCoronavirus in KolkataCoronavirus in HyderabadCoronavirus in DelhiCoronavirus in BangaloreCoronavirus symptomsCoronavirus in IndiaWhat is CoronavirusCoronavirus NewsSolar EclipseNPRWhat is NRCCAB BillCAB and NRCRTI BillPodcast newsLok SabhaShiv SenaYSRCPCongressBJP newsUIDAIIndian ArmyISRO newsSupreme Court

Get the app