NEW DELHI: On August 10, Manish Sisodia, Delhi’s deputy chief minister and education minister, reacting strongly to reports of North Delhi Municipal Corporation’s inability to pay its teachers or provide textbooks to primary school students, declared that Delhi government was ready to take over corporation-run schools in case of such deficiencies. But the issue of who should run these schools is not new. The matter has even reached the courts, while separate education committees have suggested since 1993 that the capital’s schools should be run under one administration.

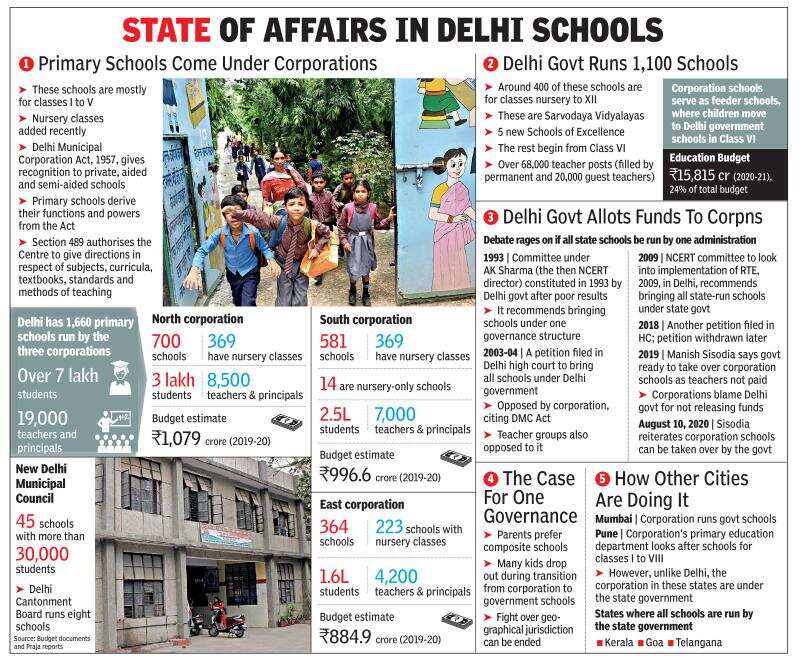

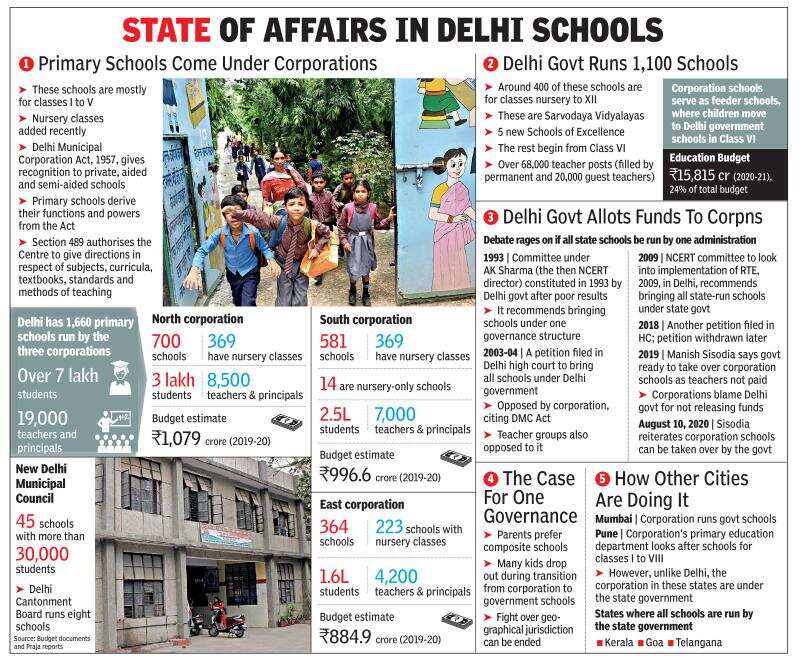

In Delhi, the primary schools with classes from I to V are run mostly by the three municipal corporations, some by the New Delhi Municipal Council and the Cantonment Board. The secondary and senior secondary schools are run by Delhi government, though around 400 of them have primary sections too. Delhi Municipal Corporation Act, 1957, obligates the civic bodies to run the primary schools. Till June 30, 1970, the erstwhile MCD also ran some 400 middle schools and 11 senior secondary schools. From July 1 that year, Delhi government took over these schools.

The corporations say it is their prerogative under the DMC Act to run the primary schools. A miffed Jai Prakash, mayor of north corporation, retorted to Sisodia’s statement with, “What the deputy CM is saying is akin to the central government wanting to take over Delhi government functions.” He argued, “Delhi government has to pay Rs 590 crore to the corporation under the head of salaries for teachers, but has as yet released only Rs 245 crore. We are also supposed to get Rs 100 crore for furniture and as cash subsidy for uniforms, textbooks and stationery, but not one rupee has been given.”

Narendra Chawla, leader of the House in the north civic body, added to the exchanges by asking why the problem of unpaid salaries and financing were never felt during the time of the Congress government led by Sheila Dikshit. “Why have these funding issues cropped up during the AAP government’s tenure?” said Chawla.

Sisodia’s ready counter was that Delhi government had given Rs 853 crore to the three corporations for primary schools, Rs 393.3 crore to north corporation alone. In a letter to the Union urban development ministry, Sisodia alleged that the fund meant for education expenses was being diverted for other uses.

While the clashing views have more to do with the politics of the city, education experts actually believe that bringing the schools under one administration offered many advantages. Advocate Ashok Agarwal pointed out that the A K Sharma Committee had recommended precisely this in 1993. “A K Sharma, who was then the NCERT director, recommended doing away with double-shift schools and bringing all institutions under one umbrella,” Agarwal noted. “In 2003-04, MCD opposed my court petition on this, citing the DMC Act. When I went to court again in 2018-19 to press for a single administration for schools, nothing could be done because of legal hurdles arising from the DMC Act.”

In 2009, an NCERT panel, working out how to implement the Right to Education Act, came to the same conclusion as the AK Sharma Commission. Shailendra Sharma, adviser to the director of education, recalled a National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration study led by Professor Nalini Juneja in early 2000. In her report, she used the analogy of a “blocked chimney” for the “failing municipal schools”, and said that parents preferred a composite school where their children could study up to Class XII without having to change institutions midway.

Having schools under one administration will also stem the falling transition rates, said Jennifer Spencer, project co-ordinator at Praja Foundation, which has regularly released study reports on the state of school education in Delhi. “The low transition rate is a major problem,” explained Spencer. “When students move from the corporation schools to secondary schools, there is a fall in enrolment, indicating a high drop-out rate.”

A municipal official, however, said enrolment was on the wane even in Delhi government schools and insisted that corporation schools too had improved over the years. “We have smart classes and have roped in NGOs to create new education models,” he said.

Sharma said an integrated school system was all the more important under the 15-year structure proposed by the new National Education Policy. “If a child joins a Delhi government school after spending almost eight years in a schooling system where the foundational and preparatory learning needs are not met, we will be back to square one. So, in the interest of children, this dual arrangement between municipal and Delhi government should cease to exist,” declared Sharma.

While Anita Rampal, former faculty of education dean, Delhi University, felt quality could improve through a “collaborative arrangement” facilitated by the state government, Spencer injected a word of caution: “It is not about moving from one building to another. Do the corporation schools have the infrastructure for additional senior classes? It is also important to look at the teacher-student ratio.”

Agarwal felt the primary institutions had the infrastructure and space that could help upgrade them into senior secondary schools. “There are close to 10 lakh children in Delhi who are out of school. So expansion is crucial in providing education to all,” he said.

Meanwhile, wracked by non-payment of salaries, teachers are ready to work in any system so long as they, or their students, are not made to suffer in the tussle between agencies. Ramniwas Solanki, general secretary, Nagar Nigam Shikshak Sangh, said, “The 19,000 teachers of corporation schools are prepared for any system, but the salaries and funds meant for education must be released on time. Teachers and students are being made to suffer in this tussle.”

In Delhi, the primary schools with classes from I to V are run mostly by the three municipal corporations, some by the New Delhi Municipal Council and the Cantonment Board. The secondary and senior secondary schools are run by Delhi government, though around 400 of them have primary sections too. Delhi Municipal Corporation Act, 1957, obligates the civic bodies to run the primary schools. Till June 30, 1970, the erstwhile MCD also ran some 400 middle schools and 11 senior secondary schools. From July 1 that year, Delhi government took over these schools.

The corporations say it is their prerogative under the DMC Act to run the primary schools. A miffed Jai Prakash, mayor of north corporation, retorted to Sisodia’s statement with, “What the deputy CM is saying is akin to the central government wanting to take over Delhi government functions.” He argued, “Delhi government has to pay Rs 590 crore to the corporation under the head of salaries for teachers, but has as yet released only Rs 245 crore. We are also supposed to get Rs 100 crore for furniture and as cash subsidy for uniforms, textbooks and stationery, but not one rupee has been given.”

Narendra Chawla, leader of the House in the north civic body, added to the exchanges by asking why the problem of unpaid salaries and financing were never felt during the time of the Congress government led by Sheila Dikshit. “Why have these funding issues cropped up during the AAP government’s tenure?” said Chawla.

Sisodia’s ready counter was that Delhi government had given Rs 853 crore to the three corporations for primary schools, Rs 393.3 crore to north corporation alone. In a letter to the Union urban development ministry, Sisodia alleged that the fund meant for education expenses was being diverted for other uses.

While the clashing views have more to do with the politics of the city, education experts actually believe that bringing the schools under one administration offered many advantages. Advocate Ashok Agarwal pointed out that the A K Sharma Committee had recommended precisely this in 1993. “A K Sharma, who was then the NCERT director, recommended doing away with double-shift schools and bringing all institutions under one umbrella,” Agarwal noted. “In 2003-04, MCD opposed my court petition on this, citing the DMC Act. When I went to court again in 2018-19 to press for a single administration for schools, nothing could be done because of legal hurdles arising from the DMC Act.”

In 2009, an NCERT panel, working out how to implement the Right to Education Act, came to the same conclusion as the AK Sharma Commission. Shailendra Sharma, adviser to the director of education, recalled a National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration study led by Professor Nalini Juneja in early 2000. In her report, she used the analogy of a “blocked chimney” for the “failing municipal schools”, and said that parents preferred a composite school where their children could study up to Class XII without having to change institutions midway.

Having schools under one administration will also stem the falling transition rates, said Jennifer Spencer, project co-ordinator at Praja Foundation, which has regularly released study reports on the state of school education in Delhi. “The low transition rate is a major problem,” explained Spencer. “When students move from the corporation schools to secondary schools, there is a fall in enrolment, indicating a high drop-out rate.”

A municipal official, however, said enrolment was on the wane even in Delhi government schools and insisted that corporation schools too had improved over the years. “We have smart classes and have roped in NGOs to create new education models,” he said.

Sharma said an integrated school system was all the more important under the 15-year structure proposed by the new National Education Policy. “If a child joins a Delhi government school after spending almost eight years in a schooling system where the foundational and preparatory learning needs are not met, we will be back to square one. So, in the interest of children, this dual arrangement between municipal and Delhi government should cease to exist,” declared Sharma.

While Anita Rampal, former faculty of education dean, Delhi University, felt quality could improve through a “collaborative arrangement” facilitated by the state government, Spencer injected a word of caution: “It is not about moving from one building to another. Do the corporation schools have the infrastructure for additional senior classes? It is also important to look at the teacher-student ratio.”

Agarwal felt the primary institutions had the infrastructure and space that could help upgrade them into senior secondary schools. “There are close to 10 lakh children in Delhi who are out of school. So expansion is crucial in providing education to all,” he said.

Meanwhile, wracked by non-payment of salaries, teachers are ready to work in any system so long as they, or their students, are not made to suffer in the tussle between agencies. Ramniwas Solanki, general secretary, Nagar Nigam Shikshak Sangh, said, “The 19,000 teachers of corporation schools are prepared for any system, but the salaries and funds meant for education must be released on time. Teachers and students are being made to suffer in this tussle.”

Coronavirus outbreak

Trending Topics

LATEST VIDEOS

City

145 inmates test positive in a day, Thiruvananthapuram central prison remains Covid-19 hotbed

145 inmates test positive in a day, Thiruvananthapuram central prison remains Covid-19 hotbed  Hundreds of birds injured due to banned manjha on Independence Day in Delhi

Hundreds of birds injured due to banned manjha on Independence Day in Delhi  Karnataka: Terrifying abduction of a woman in broad daylight caught on cam

Karnataka: Terrifying abduction of a woman in broad daylight caught on cam  Independence Day 2020: Beating retreat ceremony at Attari-Wagah Border as a part of celebrations

Independence Day 2020: Beating retreat ceremony at Attari-Wagah Border as a part of celebrations

More from TOI

Navbharat Times

Featured Today in Travel

Get the app