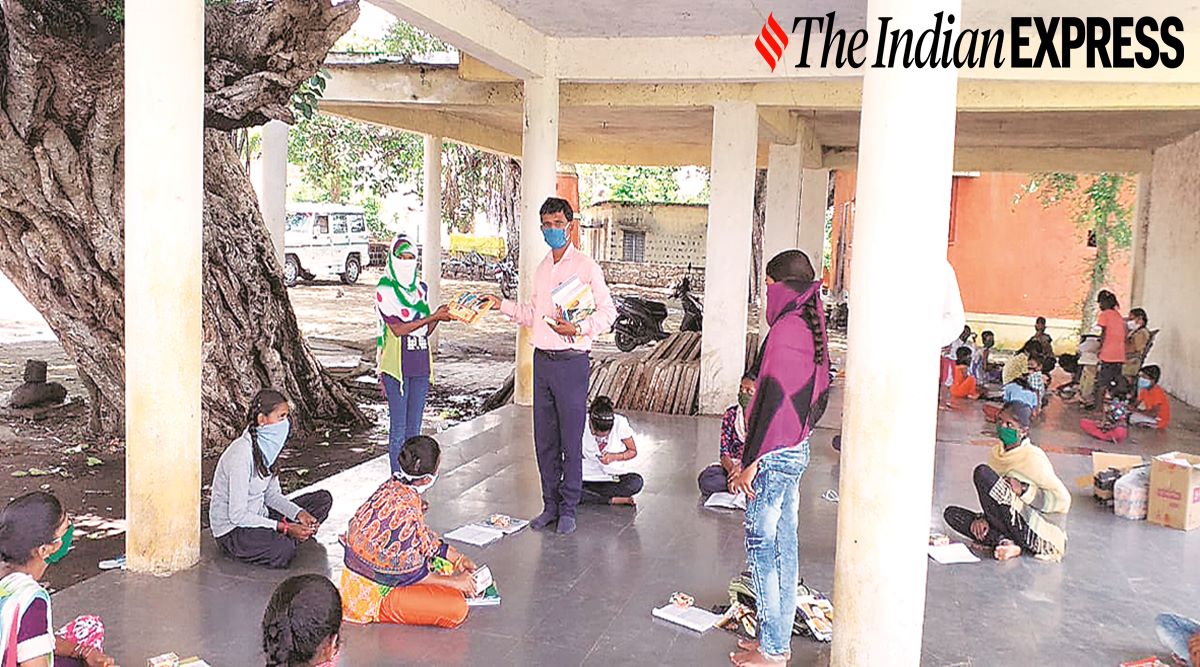

At a community school in Okali village, Gulbarga. Express

At a community school in Okali village, Gulbarga. ExpressIn the first week of June, about the time schools usually re-open after the summer break in Karnataka, the teachers of Okali Government Higher Primary School drove down to Okali village, Gulbarga district, to float an idea — if children could not go to school because of the coronavirus pandemic, what if the school came to them?

“We gathered the parents and community leaders and asked if they would let us try it. We could teach the children in small groups, with all precautions — but in open spaces. The community agreed, as they too were worried about the children being deprived of education,” says Gurubasappa Rakkasagi, a 32-year-old English teacher at the school.

In a few weeks, there were eight vatara shaale (or community schools) up and running in one village — out of community hall verandahs, temples, and other open spaces. Children troop in to the centre nearest to them and are taught in mixed groups of 20-25, through activities that aim to develop language skills, observation and maths skills.

“We had no blackboards and textbooks. So, we had to innovate and teach through storytelling and activities. For example, I would tell them a story, and ask the children to imagine and take it forward,” says Rakkasigi.

It’s an idea that has caught the imagination of educators across the state, as well as the attention of the government.

“The department had given the teachers the option of working from home, but their connection with students drove them to think of an alternative for the majority of students who do not have access to internet or technology. When we saw them taking the initiative, we provided them all the support we could,” says Nalini Atul, commissioner of public instruction, Gulbarga.

Last month, State Education Minister S Suresh Kumar called up the headmaster of the Okali school to applaud their efforts. Earlier this month, the education department issued instructions to put in place a “continuous learning programme”, Vidyagama, that has elements in common with the vatara shale model.

“We have asked teachers in each school to devise three imaginary classrooms — 1) made of students who have no access to technology 2) students who have a phone but not internet and 3) students who have access to all. Teachers will have to be in touch with the first two groups, once a week, either by going to their homes or gathering them in small numbers in common areas — and devise learning plans accordingly,” says Krishna S Karichannavar, Director of Secondary Education.

Starting from north Karnataka, the teacher-led initiative has been adopted across several districts of the state. But its seed lay in an online discussion by a group of teachers, including Rakkasagi, all members of the Bharatiya Gyan Vigyan Samiti (BGVS), who refuse to believe that online education is the only answer to the challenges posed by the pandemic.

“Technology might ensure engagement, but not learning. Some of us wondered what could be the alternative — and the idea of a vatara shaala came up,” says Chegareddy F C, a government school teacher in Belavanki, Gadag district, and vice-president of BGVS, Karnataka.

Towards the end of May, Chegareddy had turned his home into one such little school, and later opened the school library for similar interactions with small groups of students.

In the constraints, he also saw an opportunity to shift the children’s experience from “learning outcomes” and syllabus to observation, data collection and reading. “I asked the children to get an assortment of seeds from their home and plant them in small pots. Then, they had to take a worksheet and note down the time needed for each seed to sprout,” says Chegareddy.

His tasks involved the children taking an interest in their immediate environment. “I asked them to interview their fathers about the type of fertiliser they use, their experience of harvest… and write about it. It was a way to develop their language skills, make them ask questions and become little researchers,” he says. There are close to 27 such schools in Gadag alone.

Across the state, several such examples of government teachers’ innovation through the vatara shale model abound.

For Aravind Kudla, a teacher in Moodambailu in Dakshin Kannada district, who made his students write an essay on the monsoon as it washed over the state and helped them make a rain gauge to measure the rainfall, the new experiments in learning signal a hopeful realisation. “It has given us time to rethink. Before Covid, we would teach, but the child would not be able to learn. Now, I see myself not as a teacher, but as a facilitator of a child’s learning,” he says.