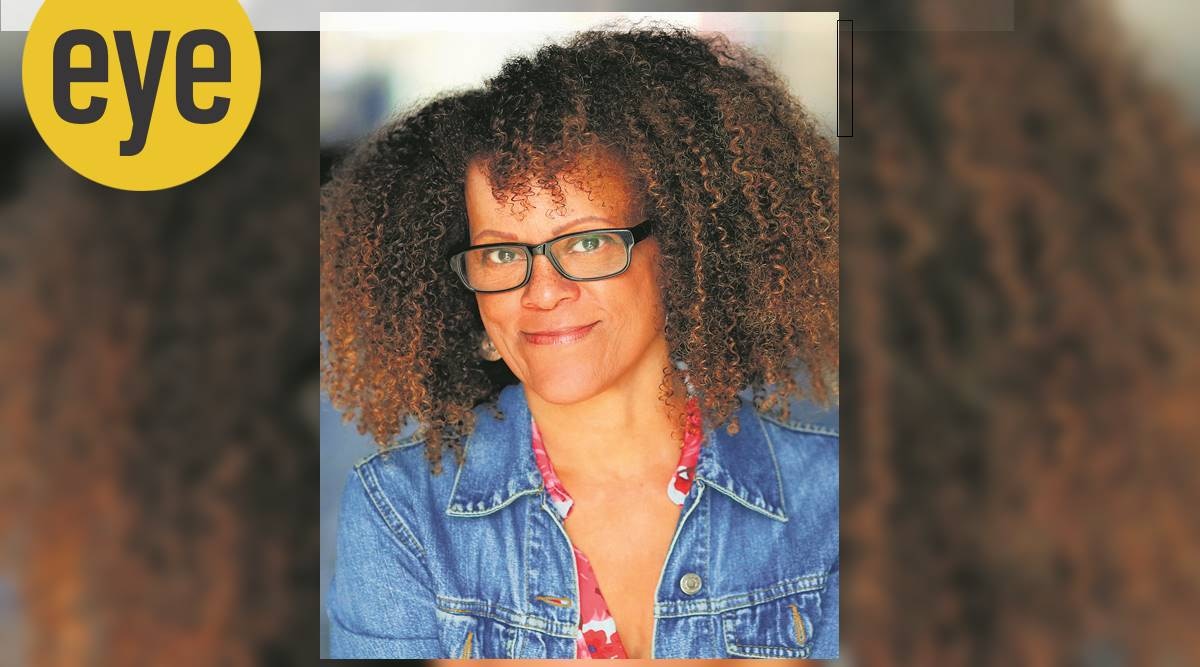

Bonfire heart: Bernardine Evaristo won the Booker Prize in 2019 for her novel Girl, Woman, Other. Evaristo shared the Prize with Canadian writer Margaret Atwood (Courtesy: Jennie Scott)

Bonfire heart: Bernardine Evaristo won the Booker Prize in 2019 for her novel Girl, Woman, Other. Evaristo shared the Prize with Canadian writer Margaret Atwood (Courtesy: Jennie Scott)A lot of the discussions in Girl, Woman, Other (Hamish Hamilton) – on race, sexuality, social media, politics – are contemporary, but there is also the legacy of the ’80s Black feminist theatre. Could you tell us about your memories of the time?

I came of age in the 1980s. I was a part of a Black women’s trans-cultural feminist community in London. We felt very disenfranchised from British society. I’d gone to drama school (Rose Bruford College), trained to be an actor but also trained to create my own theatre. There were three Black women in my course (Evaristo, Paulette Randall and Patricia Hilaire), with whom I formed a company called Theatre of Black Women in 1982. It’s Britain’s first Black woman theatre company and we formed it because we simply wanted to be a voice in theatre and there was very little work for us in the early ’80s. Nobody was going to employ us, and, if they were, we felt that we wouldn’t be interested in the kind of roles that they might be offering us. You’d be employed to play a cleaner, a cook, a prostitute or a nurse, and we wouldn’t want to play those roles. And so, we formed this company. But we didn’t all stay together. Eventually, I was the last person standing. At one point, it was too much, and, so, I left the theatre world behind. But there were lots of us who were out there, primarily in London, who came from all parts of the country, who were Black women, who were creating visual arts groups, music groups, dance groups and writers’ groups so that we could create our own platforms because there were so little opportunities for us.

Cover of Bernardine Evaristo’s book Girl, Woman, Other

Cover of Bernardine Evaristo’s book Girl, Woman, Other

In an old interview, you speak of your literary idols – Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Audre Lorde – all American writers. Were there no contemporary Black British writers who wrote of similar experiences?

No, not at all. My generation was the second generation (in Britain). The first generation that came over didn’t really create many writers. If they did, they were male. The only Black woman writer whose work I was introduced to when I was about 19 was Buchi Emecheta (1944-2017). She really is – if anybody is – the mother of Black British writing because she had come to Britain from Nigeria in 1960 and started publishing in the early ’70s about Black women’s lives in this country and in Africa. She hasn’t really been celebrated in a way that she should have been and certainly not in her lifetime. She was writing about an immigrant experience, about what it was like to be a Nigerian immigrant in the UK. My generation was born or raised in the UK and so it was very different. We just didn’t know the writers to read because literally they were not around, they were not getting published. So, we were at the beginning of a change in literary culture. We formed our own Black women’s publishing collective. Black women of that time would include women from Asia as well as women with roots in Africa and the Caribbean and so, it was a very inclusive term.

And then there were Zadie Smith, Andrea Levy, you…

Zadie’s been a big international star for about 20 years now, and, for most of that time, it was just her. I have been publishing since 1994 and I only broke through with the Booker (2019, for Girl, Woman, Other) in a big way. We have other writers now like Diana Evans, Sara Collins, Candice Carty-Williams, Afua Hirsch. Going back to the ’80s, there was almost nobody. Then you get to the ’90s and there are a few Black British writers getting published but all of them don’t stay on the concourse. By 2000, Zadie Smith is published and then there is a trickle of other Black British writers. Andrea Levy (1956-2019) was my generation. She broke through with Small Island (2004) and became a huge star. Then you get to 2020 and there is still not many of us publishing novels but there are more people publishing non-fiction. So, there are more of us around and more of us doing well, but I always have this caveat that it’s still not good enough.

How has the Booker Prize changed things for you?

I feel like I am in the heart of the system now (laughs). I had a feeling like I was an outsider even though I wasn’t really one. I have been with Penguin for 20 years and my books have been very well-reviewed, I have won awards, I am a professor at a university (Brunel University London), I’m a vice-chair at the Royal Society of Literature. In many ways, I have become a more establishment figure. I’m inside the system. But I always have to say that I am inside the system but my radical heart still beats. So, I’m still working for inclusivity, which I have always been fighting for. But the Booker took it to a different level. It completely revolutionised my career in every way possible.

Is there a limitation to the change you can bring in if you are inside the system?

I think we have to be inside and outside, because when people are outside they can make a lot of noise, they can be incredibly confrontational. Often, the people who are outside have nothing to lose. We need protests, but, at the same time, if you are not inside the system, you don’t understand how it works, and, you need to understand how it works in order to change it from within. I think that’s where we haven’t been for so long. My activism at the moment is very much from inside the system and it’s fantastic. Because I understand the system, I understand how it works and now the system is listening to me. We need to be inside and outside and we need to be working together from those two positions.

In Britain, before the pandemic, discussions were being held for the amendment of the Gender Recognition Act 2004. Trans rights again came into focus after writer JK Rowling’s recent comments on Twitter. As a trans-rights activist, where do you stand on this? Also, what are your views on literary representation of queer lives?

I don’t want to comment on JK Rowling. I think the whole trans conversation that is bubbling away at the moment is one that really needs to be discussed in a different space. I am very pro-trans. I believe in the right for people to self-identify in whatever way they want. But I also understand that we need to have conversations around this issue, because, for lots of people, it’s quite a new territory and they are struggling to navigate it.

In terms of the sexuality represented in fiction, I think there isn’t really much of it in terms of queer queer fiction. There’s the Polari Prize for Gay Fiction and it’s been going on for 10 years. That’s where you go to see who’s publishing what, and there aren’t many. Considering that there are thousands of books published every year, I think it’s safe to say that most of those books are heterosexual books. If they are not heterosexual, then they are very likely to be about gay men. So, I think there is still a taboo and a dismissiveness of queer identities in the publishing industry. I am a champion of writers of colour to be published in this country, but I am also an intersectional feminist. I am not queer but I fully appreciate that we need to have all kinds of literature represented in fiction. We don’t have that. It’s very white, middle-class and heterosexual and it shouldn’t be.

Does this have to do anything with the people who are helming major publishing houses? In the US, there have been a few changes recently. Do you see anything similar happening in the UK?

In the US, they got in people from outside the industry, with the skills to lead big publishing houses because there aren’t enough people coming up through the system. Equality starts with who you get at the entry level. There are lots of issues there but definitely the British publishing industry is overwhelmingly white and middle class. It’s also pretty female but not necessarily at the top level. It needs to change, it needs to diversify in every way possible and it knows that it needs to do this. I am part of something called the Black Writers’ Guild, which was formed very recently (in late June). It is currently talking to publishers and it will be monitoring publishers (for better representation).

You are quite vocal on Twitter about institutional racial profiling in Britain, especially by the police. Do you see this conversation moving forward in the UK after the uproar caused by the custodial death of George Floyd in the US?

The police is a very toxic institution, always has been in terms of people of colour. People of colour are disproportionately represented in the prison system, disproportionately receive heavy sentences, are disproportionately stopped and searched. It’s been going on since, at least, the ’70s. I don’t know if you saw it in the papers, but there was an incident (last month) in Islington where a cop was wrestling a Black man and put his knee on his neck. So, I don’t know what the answer to that is. I don’t think anyone knows what it is. But it has to be a top-down approach from the police and I don’t know what they are doing.