A family mourns the loss of a loved one at a Delhi hospital. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

A family mourns the loss of a loved one at a Delhi hospital. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Could she be really gone?” It is something Guwahati-based Lonie Chaliha, a retired school teacher in her sixties, finds herself wondering months after her sister, Julie Dutta died. In the last five years that Julie battled cancer in Kolkata, Lonie was a constant source of comfort. “We were close in a way only sisters can be: we would talk every night, we would share everything,” she says. Every time Julie underwent a major chemotherapy procedure, her sister would fly down to Kolkata. This March was no different. Julie, also in her sixties, had undergone a procedure and Lonie was with her sister. “But mid-March I came back to Guwahati to sort out some work, thinking I would go back in a few days,” she says.

Then came a pandemic, a lockdown, and a piece of news she was barely prepared for: her sister passed away on the morning of April 6, her husband by her side. When her other brother had died of an illness in 2008, Lonie remembers how starkly different that experience was. “Death in our culture is rarely quiet. Everyone visited, we could share our grief, we could remember the good times with him. In normal times, it would have been a similar farewell to Julie, too, but all I saw were photographs of four people taking her away to a crematorium.” The sight saddened her even more because the vivacious, stylish and sophisticated Julie simply loved being around people. A small shraadh was held at Julie’s home in Kolkata, with only her husband and the priest in attendance.

Read | Karnataka: Lag in death registrations impacts Covid-19 mortality assessment

As the days go by, Lonie says, instead of ebbing, the grief has become more severe, more painful, and sometimes, even punitive. Questions plague her the most in the quiet of the night, when everyone has gone to sleep, just around the time she would usually get a call from Julie, and she would say, in her signature singsong style, “Ki koriso, Lonz? (What are you doing?)”

Relatives perform the last rites of a COVID-19 victim at the Nigambodh Ghat in Delhi. (Express Photo by Abhinav Saha)

Relatives perform the last rites of a COVID-19 victim at the Nigambodh Ghat in Delhi. (Express Photo by Abhinav Saha)

Echoes of Chaliha’s distress can be heard in a village in Bihar’s Begusarai, inside a house in Canada, in Mumbai’s Dharavi, in a busy home in south Delhi — and in countless other homes grappling with solitary grief. With the fear of transmission of the coronavirus and social distancing protocols, mourning is no longer the community experience it always has been. Children have been unable to attend the last rites of a parent, families have had to watch a loved one’s funeral on WhatsApp video calls, an ageing mother was unable to console her young daughter who lost her husband — these are not stories of resilience thrown up by the pandemic, but instances of unimaginable grief boxed in a room. “Being consoled is an important stage of grief and, in the last few months, in many cases, that stage is being skipped,” says Delhi-based clinical psychologist Sarika Boora.

The last time Surinder Jeet Kaur, assistant commissioner of Delhi Police, spoke to her husband was the day before he was put on ventilator for COVID-19 related respiratory illness on May 22. He sent Surinder a series of WhatsApp messages about their bank details, and told her he was having difficulty breathing over a video call. That was also the last time Surinder saw her husband. He died 23 days later.

Don’t miss from Explained | India coronavirus numbers: Mizoram only state with less than 1,000 cases

Two months on, Surinder is stricken by the fact that she could not give him a befitting farewell. “We bathe our beloved, make them wear new clothes, put some Gangajal in their mouth. I didn’t even get to see his face. He was a good man, he deserved more,” says Surinder. Nor could her 26-year-old son attend the funeral. He watched his mother perform the last rites from a relative’s home in Vancouver, Canada. “What can be more painful than losing my partner of 28 years and not even having our son to hold and cry?” says Surinder.

Urns holding ashes hang from a tree at a cremation ground in Chandigarh. (Express photo by Jasbir Malhi)

Urns holding ashes hang from a tree at a cremation ground in Chandigarh. (Express photo by Jasbir Malhi)

The virtual “last rites” ceremony, says Bhavna Barmi, a Delhi-based clinical psychologist, does not help someone accept reality with conviction. “The lack of social support can also lead to instensification of sadness,” she says.

Some families were even more unfortunate. “When my brother-in-law passed away in Kolkata, the hospital told his wife that there is a queue for cremations and that ‘inka number aayega.’ His body was kept in a morgue. Two days later at 8 am, the hospital called and said that he had been cremated at 3 am. The family didn’t even get to see his face,” says Mumbai-based freelance journalist Sohini Mitter.

Read | Pune: Liquid oxygen tank diverted from Aundh Civil Hospital to Sassoon General Hospital

In June, when Delhi witnessed a spike in coronavirus cases, packed ambulances and rushed farewells were the norm at crematoriums. At the Dayanand Muktidham Cremation Ground and Electric Crematorium in south Delhi, urns of ashes still lie in the storeroom — awaiting the return of children of the deceased from faraway countries. Dharamveer, 32, a priest at the crematorium, says he had never seen such sights before. “I see relatives in PPE kits crying alone, standing apart, unable to hold each other. Earlier, 50-100 people would come for the cremation, now the number is down to five or 10 because of the rules,” he says. Both Penzy Morgan, the caretaker of the Indian Christian Cemetery in Delhi’s Paharganj, and Haji Kallu of the Hauz Rani Kabristan in the city narrated similar stories — of hesitation at graveyards and fewer family members. Kallu said, “In the last 50 years, I have never seen such a change in how we mourn the dead. It’s sad to see such small farewells, to know that people are hesitant to meet each other, of saying goodbye… Yeh virus kaisa samay leke aaya hai? (What times has this virus brought?)”

Even at 92, Anand Mohan Zutshi Gulzar Dehlvi was the life of mushairas in Delhi, and a roaring applause followed every time he read a nazm. In June, when he passed away at his Greater Noida home — a week after recovering from COVID-19 — it was truly the end of an era. “Had it been ordinary times, there would have been thousands of people at his last rites… family, friends, neighbours, fans of his work. But only 10 came because of the prevailing situation. My wife and children were in Pune, my sister was in the US, and throngs of Papa’s fans watched it on Facebook,” says the poet’s son Anoop Zutshi. “Since it was just mom and I, there was no solace, no one to hold our hands or hug us,” he says.

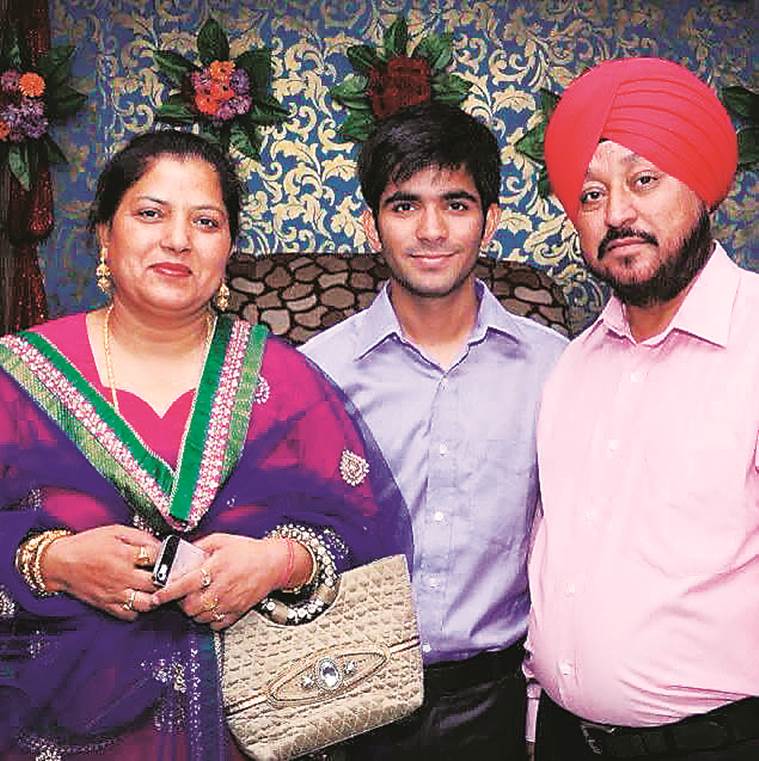

Surinder Jeet Kaur with her husband and son.

Surinder Jeet Kaur with her husband and son.

In two decades of living in Aizawl’s Chawlhhmun locality, Margaret Zama, a professor of English from the Mizoram University, says she has never missed a single funeral. But since the lockdown, she hasn’t attended even one — completely unheard of. Because death in Mizoram is rarely a private affair. “Mizo funerals are not just attended by relatives, friends and acquaintances but by complete strangers too,” says Zama. When someone dies in Mizoram, loudspeaker announcements (tlangau) are made to inform the entire locality and the Young Mizo Association (YMA) — the most influential organisation in the state — swings into action to make arrangements for the funeral. Everyone in the neighbourhood participates, whether it is to build a coffin, dig the grave, cook for the family, or sit together and sing funeral songs through the night. In the post-COVID world, the funerals are shorter and only a few participate — rituals have been cut short or done away with.

Read | SC takes note of letter seeking ‘martyr’ status for Covid warriors

When his father died in 2014, Kima a blogger and software developer from Aizawl, recalls how the entire neighbourhood showed up to carry out the customary practices — one of which involved offering to sleep over at the deceased’s house to give the family company. At a recent funeral, Kima saw the stark, unsettling difference. “There were few people, everyone wore masks, everyone stood far away from each other,” he says.

For most of the families, death in the time of the coronavirus already compounds a time of great tragedy. In May, a PTI photo of 40-year-old Ram Pukar Pandit sobbing at the Delhi-UP border went viral, as the Begusarai resident, overwhelmed by the news of his infant son’s death, struggled to return home. He finally made it home, but not in time for the funeral. The family did organise a small puja at home when he reached. Even now, he regrets that he doesn’t have a single photograph of his nine-month-old baby. Every time he thinks of his little boy, memories of a video call from Begusarai to Delhi, when the baby was born in 2019, float back to him. “I never met my son, I wasn’t here when he was born. I couldn’t visit home because I had to earn money, and I couldn’t make it back in time for his last rites either. Every time I think of him, I feel like I will go mad,” says Pandit. More sorrow befell the already struggling family. “Before she could even get over the loss of our child, my wife lost her father to prolonged illness. The lockdown is strict here, we are unable to meet any family… Dukh itna hai jaise chhaati pe chattaan rakh diya hai kisi ne. Upar se kaam kuch nahi hai, na paisa (I feel like I am being crushed by grief. On top of that, there is no work or money),” he says, over the phone from his village.

Sisters Julie Dutta and Lonie Chaliha.

Sisters Julie Dutta and Lonie Chaliha.

In Kerala, 22-year-old Akhil, son of nursing officer Ambika PK who died of COVID-19 in May in Delhi, has “reserved his nights for sadness” and worrying about how the loss is affecting his younger sister. The days are for arranging insurance paperwork and other chores. “I don’t have the time to be sad… Only at night, maybe, when all the work is done. I have recurring nightmares, very bad dreams of being alone in a forest or watching death… Then there is news of a landslide, a plane crash, increasing deaths…”

As mortality becomes a daily graph to be reckoned with, the lives and deaths of others add up to a collective grief — without a catharsis. Boora says that a lot of her clients, too, are “in turmoil because of … news of tragedies and deaths on TV. The loss of a loved one is accompanied by other drastic changes such as loss of job, reduced salaries, strained relationships due to lockdown, and worrying news from across the world.”

Read | Odisha: Sero survey shows prevalence of anti bodies in 1 in 3 persons in Berhrampur

A 36-year-old doctor at the Safdarjung hospital in Delhi, who has been on COVID-19 duty every month for two weeks since March, says that the medical fraternity is “stewing in collective sadness.” “When cases were peaking in the city, we felt a sense of helplessness, especially in the ICU. Since family members can’t meet patients, we often were the route through which they last spoke to their loved ones. It was traumatising . . . Apart from deaths of patients, we lost colleagues, family members or friends to COVID-19 and other ailments,” he says.

Sohrab Farooqi and his mother.

Sohrab Farooqi and his mother.

Some are trying to move on, through self-devised routines. Sohrab Farooqui, 26, a hotel management student in Mumbai’s Dharavi, has focussed all his energies on working out and exercise, after his mother passed away due to Covid-19 in April. “She died due to negligence, no help reached her in time. I am so angry, I am hurt, I am broken… Maa ke jaane ke baad kuch nahi bacha. I have suppressed my anger by working out. It helps me. I also visit her grave every Thursday,” he says.

Akhil is wrenched by the thought of losing his sister. He says, “She doesn’t talk to me, maybe she blames me… My mother and sister wanted me to stay back in Delhi when I visited in February but I didn’t. Her nature has also changed, she talks less ever since mother passed away. I didn’t know I would undergo such grief at such a young age. No one taught me how to deal with it.”

Read | US warns 5 Indian firms selling unapproved drugs, Covid ‘cures’

It is this lesson that Dr Heena Ali is struggling to broach with her children after their father — Dr Javed Ali, a government doctor in Delhi — died in July, while treating COVID-19 patients since March. “My six-year-old son thinks his father is at his grandfather’s house so he calls him every day and asks him to return Papa… I have noticed that my daughter, who is older, understands that her father is no more. She has immersed herself in studies. This is her response to grief. They are the ones consoling me,” says Dr Heena. “As for me, yeh zakhm zindagi bhar ka hai (this is a wound for life) . . . I can’t even describe my pain to you, I can only feel it.”