Muska Najibullah daughter of former Afghanistan President Mohammed Najibullah.

Muska Najibullah daughter of former Afghanistan President Mohammed Najibullah.

Muska Najibullah (37), daughter of former Afghanistan President Mohammed Najibullah, has been living in India with her mother Fatana Najib and two sisters. While the family had evacuated to India when the Mujahideen took over Kabul in 1992, her father Mohammed Najibullah, who had started as a member of the communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) and was named by the Soviets as the President in 1987, had stayed on. Najibullah and his brother Shahpur Ahmadzai were brutally killed by the Taliban in 1996. Najibullah’s government (1987-1992) had reportedly helped Sikhs and Hindus by issuing speedy passports and visas, when the mass exodus of minorities started from Afghanistan.

The mass exodus of Sikhs and Hindus from Afghanistan had begun in 1992 after the Mujahideen took over. What do you have to say about the current exodus, which has started after the Kabul gurdwara attack in March this year. Less than 700 Sikhs and Hindus are left in Afghanistan.

Religious persecution and social exclusion are the strongest motivators for Hindus and Sikhs leaving Afghanistan. There is only so much a community can tolerate. Many are struggling with prejudice, and facing an uphill battle to preserve their cultural and religious traditions. Afghan Sikh and Hindu communities are an integral part of our rich culture, religious heritage and historical fabric. Although Afghanistan is almost entirely Muslim, our constitution, drawn up after 2001, theoretically guarantees the right of minority religions to worship freely. Despite it imitating some of the best model constitutions of the world, there is inadequacy when it comes to supporting a pluralistic system of democracy. The Afghan legal system has relegated Sikhs and Hindus to second-class citizenship. On one hand, it guarantees equal rights to all Afghan citizens (Article 22) but then contradicts itself by excluding a section of the population (Article 62). If the political system is frail and cannot protect Afghan minorities from varying ethnicities or religions, this impacts our country’s ethno-religious diversity and heritage.

So what, according to you, are the main reasons for Hindus and Sikhs leaving Afghanistan now? What has mainly triggered this fresh exodus?

A complete generation of Afghans has witnessed only conflict for the last 40 years. While the political turmoil has impacted the lives of every Afghan adversely, religious minorities like the Hindus and Sikhs are in particular most vulnerable. The recent attacks at the 400-year-old gurdwara was perhaps the final straw for this dwindling community and triggered another exodus. If there is growing fear and insecurity within an already small community, what makes you think the rest will want to stay?

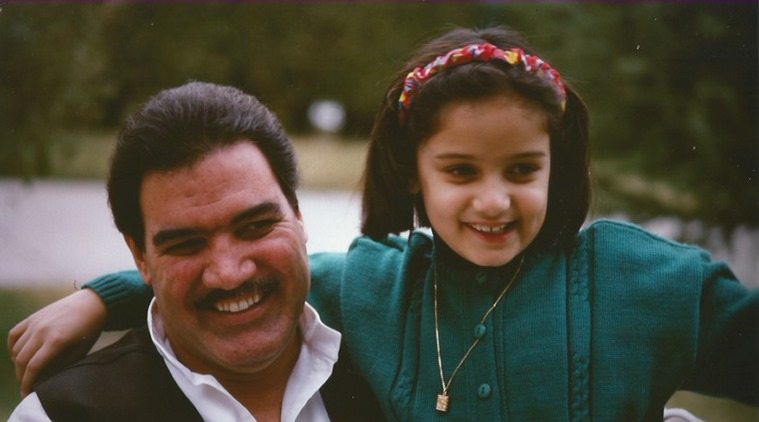

Muska Najibullah with her Father Mohammed Najibullah.

Muska Najibullah with her Father Mohammed Najibullah.

These two minority groups were once thriving with a substantial involvement in Afghanistan’s trade and business. Many Afghan Sikhs stand out from the Muslim crowd, and have become an easily identifiable target for crime and harassment, including kidnappings. While their mass exodus from Afghanistan began with the coming to power of the Mujahideen in 1992, the recent violent attacks are a reminder of those troubled times. Their population has shrunk from about 2,50,000 to less than a thousand, which is extremely concerning. Often, it takes exile and exposure to mainstream media to realise just how unfair the state and society has been towards the Hindu and Sikh community. Decades of oppression have obviously left their mark on this community, and their fear has manifested itself in other ways, too.

Despite these challenges, the community still feels a powerful sense of belonging to Afghanistan. This is the land of their ancestors. If the Afghan government makes a sincere effort to ensure their security, there would be no reason for them to be displaced or to leave their homeland. Being Afghan is about more than religion, and as possibly the country’s oldest inhabitants, the Afghan Sikhs and Hindus are an integral part of our identity. Not only do we owe them but more importantly we owe it to the country to preserve a more diverse and tolerant Afghan society.

During his Presidency, what role did your father play in helping Hindus and Sikhs in 1992, when they had started leaving before the Mujahideen took over?

During my father’s presidency, Hindus and Sikhs were living in harmony with Muslims, practicing their faith freely in Afghanistan. Many Hindus and Sikhs, with their typical business acumen, had established factories in Kabul and operated a healthy export business, trading in Afghan goods such as dried fruit, textiles and precious stones. Their social status prior to the 1990s had also enabled them to be a part of the military and civil services, and some even took up high positions in Hezb-e Watan Party (earlier People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan or PDPA). My father never believed in marginalising people based on their religion or ethnicity. His vision was a unified Afghanistan. In fact, in his National Reconciliation Policy (NRP), he called for an inclusive political settlement that would bring about a cease-fire with the Mujahideen. During the transitional period when my father declared a unilateral ceasefire, he cautioned minorities of their vulnerable position and supported those who chose to leave the country. His government coordinated the resettlement of Afghan Sikhs and Hindus to other countries like India and issued them speedy passports and visas.

How are you seeing the current US-Taliban peace deal in Afghanistan?

My country has been burning in the fire of war for nearly 40 years now. This war has inflicted all kinds of injury on every aspect of our country. From the large scale slaughter of people, to the destruction of economic infrastructure, to the traumatised psychology of the war-affected. From the violation of the rights and freedoms of women and children, to corruption at the top-level and the crumbling of the rule of law.

Every Afghan wants peace. However, to extricate Afghanistan from this bitter state requires a transformational approach. In principle, Afghanistan can sustain itself if it becomes a stable nation funded primarily by domestic revenue and a surplus sufficient to finance a security establishment capable of withstanding external foreign threats, and more importantly a government and administration that has strong legitimacy and capacity to control threats.

More importantly, we need to change the narrative of peace. We need to term this peace deal not between an external power and the nation but a peace process that is predominantly Afghan-led and Afghan-owned, while requiring clear and committed support from the countries of the region and at the international level.

This ongoing conflict can end only if peace is predominantly led and owned by our own people. We’ve lost nearly 40 years with roundtable discussions. Where is the voice of the common man?

The Afghan National Security advisor, Hamdullah Mohib, visited your father’s grave in Gardez of Paktia this year. The Afghan government has also proposed to embellish his grave now. But you and your mother have been demanding an enquiry into his assassination.

The recent visit was a personal and humble gesture as well as the government’s offer to repair my father’s grave. It has been 24 years since my father’s death yet he still continues to stage a comeback, riding on the popularity wave among violence-weary Afghans who still love him for what he stood for and believed in. He might be gone physically but young Afghans who have never met him carry his pictures and watch his speeches on YouTube. Today, he rests among his people and among the many other graves of ordinary Afghans who too lost their lives.

More than repairing his grave, I think the Afghan people want to address a bigger question which remains unanswered. What exactly happened at the UN compound on September 27, 1996? Who was behind the assassination of President Najibullah and his brother? What was the motive and why? How did they manage to kill a country’s President and his brother? My mother’s statement was an official request from our family to the Afghan government to undertake the necessary measures in opening an inquiry. A commission must be set by the government to inquire into the facts and circumstances of the assassination. The duty of determining criminal responsibility for the assassination remains with the Afghan authorities. Before we mark a day after him, before we build his grave, before anything else, we need to investigate and find out the truth.

So has there been any response to your mother’s request for an enquiry commission?

We are yet to hear from the Afghan government. There is no reconciliation in the absence of truth and justice. Like the rest of the world, we found out about my father and my uncle’s death on a television screen. We need absolute closure on this. We are still waiting for it, 24 years later.

For you and your family, how has it been living in India for 28 years?

India has been my second home, as I’ve spent more years here than in my own country. India and its people has given us a second chance at life, for which we are forever indebted. India welcomed us during the darkest period of our lives when we had no other support. I’ve grown up here, studied and worked. I’ve traveled to many other countries, but there’s none like India. It is a land of diverging layers and complexities and there is a distinct earthy smell in the air that makes you feel alive. Geographically, it’s also close to Afghanistan, where my heart is. Whenever I travel to India and the plane crosses over Afghanistan, it makes me very nostalgic.

Have you ever been to Afghanistan since you left your country? Do you wish to go back someday and take your father’s political legacy ahead?

Unfortunately, after coming to India at the age of eight I have never been able to go back home to my own land, which is so deeply engraved in my blood. I haven’t even visited my father’s final resting place (grave). There are safety and security issues but I long to go back. Someday, that path to my own country, will open for me, I believe. For now, I enjoy my country’s food, culture, literature and people, from a distance. My father’s dream was a peaceful and united Afghanistan. Today, every young Afghan dreams of this. We are lucky to have a country full of ambitious, driven, passionate Afghan youth who can take forward my father’s vision. Currently, I am working on cultural projects to take ahead my father’s dream of a united and peaceful Afghanistan with a rich culture and heritage. The photo exhibition on the ‘Kabuliwala Afghans of Kolkata’ is a testament to this. I also co-authored a cultural guidebook on Afghanistan and persevering towards other projects to sensitise people and shift mindsets about Afghanistan, and how misunderstood my country is. The day I am able to visit Afghanistan, I want to spend time with my own people, smell that fresh mountainous air, let my feet touch its soil and just soak myself into the world that I was born in. One day, inshallah.