DCPCR will track attendance when kids return to school.

DCPCR will track attendance when kids return to school.

Four primary challenges have cropped up in the realm of child rights in Delhi with the Covid outbreak and the lockdown — child labour, homelessness, reversal of progress in child healthcare, and school drop-outs — which are going to get compounded over time, recently appointed chairman of Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights Anurag Kundu has told The Indian Express.

Kundu has been in office as chairman for a month now and said that while the entire government machinery is involved in Covid, it will also need to address these allied challenges.

“Not just me, the ILO (International Labour Organisation) has said that millions of children are at risk of being pushed into child labour and it has already started to happen, not just in Delhi but in all cosmopolitan areas… Secondly, I have lived in Delhi for 30 years and I have never seen homeless families, with little children, in the scale that we are seeing today, and homelessness is the starkest manifestation of what poverty looks like,” he said.

The third challenge he pointed to is a consequence of the diversion of health machinery to Covid care, which, he said, is leading to neglect of “core” functions — such as pregnancy care in institutions and immunisation of children to diseases such as tuberculosis — in which progress has been made over years. The final point he flagged is a consequence of the first two challenges — stating that children, especially boys, being pushed into child labour will result in reduced school attendance and increased drop-outs.

Kundu said that the commission, with the government, is in the process of working out micro-targets that have the “capability to defeat the seemingly insurmountable challenges ahead”.

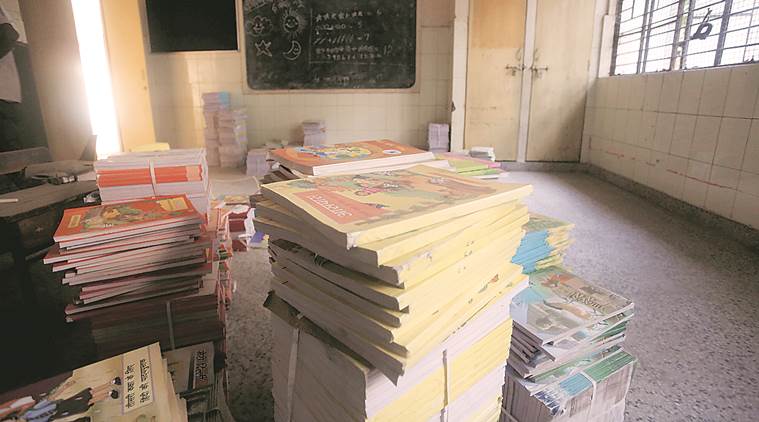

“Attendance is the sharpest indicator of a child being in an adverse situation … If a child doesn’t attend school for a long time, it could hint at the child being involved in child labour, to early marriage in case of girls, and a range of other issues tied to POCSO and juvenile justice. So we’re trying to work towards a series of actions if a child has less than 33% attendance — a call to the family, visit to the home, a conversation between the child and the counsellor — so that there can be timely interventions,” he said.

He also said that during his time as chairperson, he is looking to reposition the approach to addressing child rights issues: “If we take the case of POCSO, so far our approach has been that every time a sexual assault is reported we try to make sure the accused is chargesheeted… a reconciliation between the criminal justice system and the restorative justice system will be a focus point during my tenure. This will involve financial compensation to the survivor, emotional and mental well-being of the child, education integration of the child back to school, and medical needs of the child over time… We have now started a review of all sexual assault cases that have come to the commission over the last three-odd years. It’s an approach — it is applicable to cases of POCSO, child labour and elsewhere.”