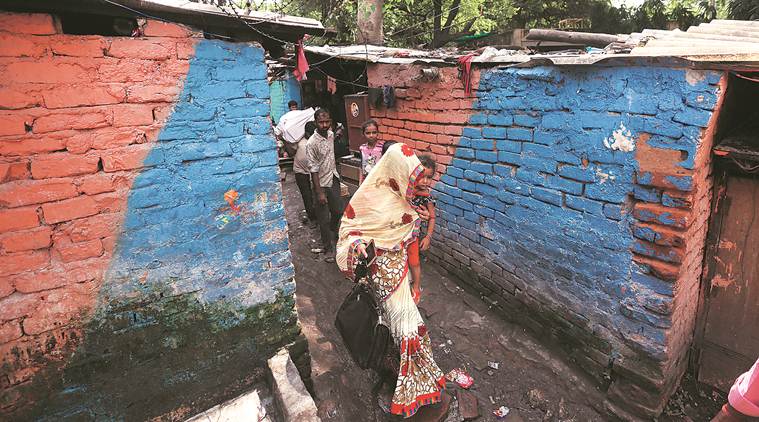

During the lockdown, nine welfare schemes were announced for different target groups and with different eligibility documents to claim benefits.(File/representational)

During the lockdown, nine welfare schemes were announced for different target groups and with different eligibility documents to claim benefits.(File/representational)

Had all households possessed the various social security documents required for different welfare schemes they are eligible for, they would have — on an average — received 2.3 times more monetary benefits from the government at the height of lockdown, found a study of almost 200 households in two Northwest Delhi slum areas.

The survey, conducted by Saudamini Das and Ajit Mishra of the Institute of Economic Growth between April 22 and May 8, studied the efficacy of various welfare schemes, extended by the Central and Delhi governments, during this period among 195 households in slum areas of Zakhira and Kirti Nagar. The study’s authors said the findings suggest a streamlining of the multiplicity of welfare schemes could have helped people gain more benefits. Of these, most household heads were wage labourers; self-employed as tailors, carpenters and electricians; commercial drivers of autorickshaws and e-rickshaws; and working small private jobs such as security and housekeeping with an average family size of 5.8 persons. Their average pre-lockdown daily wage had been Rs 426 and 98% of them were not earning anything at that stage of the lockdown.

During the lockdown, nine welfare schemes were announced for different target groups and with different eligibility documents to claim benefits. Four of these were from the Delhi government — separate free food supply distribution schemes for those with and without ration cards, and two schemes for one-time payment to transport service providers and construction workers. There were five different schemes from the Centre for beneficiaries of AAY, Ujjwala Yojana, PMJDY, National Social Assistance Programme and PM Kisan Yojana. The survey found that 76% of these poor households had benefited from at least one of the nine schemes, but the average gain across households had been just worth Rs 984 — including the monetised values of grains, dal and LPG cylinders — per household for a month.

The survey also found that if all eligible households had actually received their due benefits — and if all households had possessed ration cards — this average of benefits would have been worth Rs 2,251.3.

“The gaps in distribution suggest a few things looking forward. Instead of targeting so many different smaller groups through multiple schemes, it might be more effective to have fewer schemes which can reach more people and which are implemented more effectively. Among the extremely poor migrants, there were many who didn’t have ration cards, pointing to the urgency of the unified ration card scheme,” Das said.